Many depictions of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ in nineteenth-century British literature offer a positive, idealised, even elegiac portrayal of the settlement of New Plymouth. After all, according to the myth popularised by Felicia Hemans, these were the brave men and women who laid the foundation of a great nation. However, the mythology of the Mayflower was also put to less celebratory uses. Perhaps the most well-known example is Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ (1848); a controversial mid-century poem that grapples with issues of race, slavery, and injustice from an explicitly abolitionist perspective. Originally intended for publication in the 1848 edition of The Liberty Bell, an antislavery annual based in Boston, Browning – born in County Durham – feared the work was ‘too ferocious, perhaps, for the Americans to publish’. [1]

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elizabeth_Barrett_Browning.jpg

Despite Browning’s anxiety ‘The Runaway Slave’ was carried by The Liberty Bell and became one of her best known poems on both sides of the Atlantic. The manuscript of the poem was originally titled ‘The Black and Mad at Pilgrim’s Point’, indicating how foregrounded issues of race are to the work, but also the centrality of Plymouth Rock to the narrative. [2] The speaker of the poem, an unnamed fugitive slave woman, stands at Pilgrim’s Point in an ironic inversion of the history of liberty that had become an integral part of the Mayflower narrative and American national identity. The poem opens with the speaker addressing the Pilgrims directly:

I.

I STAND on the mark beside the shore

Of the first white pilgrim’s bended knee,

Where exile turned to ancestor,

And God was thanked for liberty.

I have run through the night, my skin is as dark,

I bend my knee down on this mark . . .

I look on the sky and the sea.

II.

O pilgrim−souls, I speak to you!

I see you come out proud and slow

From the land of the spirits pale as dew . . .

And round me and round me ye go!

O pilgrims, I have gasped and run

All night long from the whips of one

Who in your names works sin and woe.

III.

And thus I thought that I would come

And kneel here where I knelt before,

And feel your souls around me hum

In undertone to the ocean’s roar;

And lift my black face, my black hand,

Here, in your names, to curse this land

Ye blessed in freedom’s evermore.[3]

Through the voice of ‘The Runaway Slave’ Browning is directly challenging the historical association of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ as the origin myth for a nation founded on liberty. In its stead, Browning presents another association, that of the intimate connection between race-based slavery and the settlement of North America. The runaway slave sees only the connection between the pilgrims and an inhuman system of bondage: ‘O pilgrims, I have gasped and run/All night long from the whips of one/Who in your names works sin and woe’. She has come to the edge of the American continent, faced with the sea – again, inverting the narrative of settlement and freedom in a boundless new land, to denounce the separatists: ‘And thus I thought that I would come/ […] /Here, in your names, to curse this land/ Ye blessed in freedom’s evermore’. The word ‘blessed’ mocks the supposed religious virtue of the Pilgrim Fathers. From these opening stanzas alone we can read how the poem makes powerful and pointed use of the Mayflower narrative in order to demonstrate the hypocrisy of an origin myth based on freedom and liberty for a nation that profited from slavery.

Frontispiece from The Liberty Bell. Public Domain. British Library. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/american-abolitionist-literature-magazine

‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ is written in the form of a dramatic monologue, a popular genre of mid-century poem, popularised by Barrett Browning and her husband Robert Browning in works such as ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ (1836) and ‘My Last Duchess’ (1842). Often written in long-form, dramatic monologues feature a single speaker addressing the reader with a narrative-based account of their life. Taking influence from Romantic-era poetry, dramatic monologues feature a deep focus on subjective emotions and interiority, however, the genre frequently extended the Romantic lyric ‘I’ into a form of characterisation that often diverged starkly from the poet’s personal voice, as is the case with ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’. The dramatic monologue has been described as a ‘poetry of sympathy’ in which the reader is given ‘facts from within’.[4] As such, dramatic monologues are often used as vehicles for the discussion of social issues and political concerns. Cornelia D. J. Pearsall comments on the achievements Browning made in her use of the genre:

Perhaps no Victorian poet used the genre of the dramatic monologue to more powerful polemical effect than Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whose poem “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” first appeared in an American anti-slavery publication in 1848. […]

She uses the genre’s tendency to feature speakers in extremity to powerful dramatic effect, seeking for a multiplicity of transformations to take place not only in the course of the poem but also in the world beyond it. In such works we may trace the creative transformation of violence, as destructive acts mutate into inventive ones through the very medium of the monologue.[5]

Dramatic monologues have the advantage of creating a sense of emotional immediacy via the speaker’s direct address to the reader, which is taken full advantage of by Browning in ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’. Indeed, Browning does not shy away from articulating the worst cruelties associated with slavery in the United States.

Ornate cover from The Liberty Bell annual (1848). Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8e/Libertybell-cover.jpg

As the poem progresses, the story of the fugitive slave is revealed to be one that includes a brutal personal history of rape, torture, and infanticide. The most controversial stanzas of the poem involve a detailed account of the distraught slave mother killing her infant child, which was born as the result of rape by her master:

XVIII.

My own, own child! I could not bear

To look in his face, it was so white.

I covered him up with a kerchief there;

I covered his face in close and tight:

And he moaned and struggled, as well might be,

For the white child wanted his liberty—

Ha, ha! he wanted his master right.

XIX.

He moaned and beat with his head and feet,

His little feet that never grew—

He struck them out, as it was meet,

Against my heart to break it through.

I might have sung and made him mild—

But I dared not sing to the white-faced child

The only song I knew.

XX.

I pulled the kerchief very close:

He could not see the sun, I swear

More, then, alive, than now he does

From between the roots of the mangles . . . where?

. . I know where. Close! a child and mother

Do wrong to look at one another,

When one is black and one is fair.[6]

The fierce abolitionist invective of ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ helped to cement Browning’s literary celebrity; as Marjorie Stone and Beverly Taylor comment, the poem

established her trans-Atlantic reputation. By mid-century, she stood with Tennyson among the first rank of English poets, celebrated not only by the public, but also by other writers and artists. She was the only woman writer included in the list of “Immortals” drawn up by the zealous young Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848.[7]

Indeed, the influence of the work has lasted until the present day; it is frequently anthologised and taught on degree-level literature courses. Deborah Anna Logan gives a concise account of the poem’s continuing power and influence:

With a rhetorical power undiminished in the century and a half since its composition, this poem provides a graphic depiction and vindication of infanticide, a topic with an unparalleled capacity to arouse class anxieties about fallen sexuality, particularly when complicated, as in this poem, by racial issues. Although its author is removed racially, geographically, and economically from the Runaway Slave’s experience, this dramatic monologue compellingly captures the spirit of rage engaged by the triple dehumanization of one race, one class, and one sex by another.[8]

Whilst the remarkable use of rhetoric and invective has been noted by many critics, academic attention towards the use of the Mayflower narrative and the Pilgrim Fathers has not been as sustained. In addition to the opening, the spirits of the Pilgrims are a constant presence in the poem. For instance, when describing the murder of a former lover by cruel slave-masters, the names of the pilgrims are once again invoked:

[…] I crawled to touch

His blood’s mark in the dust! . . . not much,

Ye pilgrim-souls, . . . though plain as this! [9]

The entire poem is as much an address to the ‘Spirits’ of the Pilgrim Fathers as the reader. Browning is aiming for the heart of the Mayflower myth: if we are to consider the Pilgrim Fathers as the founders of America, she asks the reader to consider what sort of nation they have created. Towards the end of the poem the runaway slave again calls out to the ghosts of the Pilgrim Fathers only for them to be replaced by their ‘sons’ in the form of slave catchers:

XXIX.

I look on the sea and sky!

Where the pilgrims’ ships first anchored lay,

The free sun rideth gloriously;

But the pilgrim-ghosts have slid away

Through the earliest streaks of the morn.

My face is black, but it glares with a scorn

Which they dare not meet by day.

XXX.

Ah!–in their ‘stead, their hunter sons!

Ah, ah! they are on me–they hunt in a ring–

Keep off! I brave you all at once–

I throw off your eyes like snakes that sting!

You have killed the black eagle at nest, I think:

Did you never stand still in your triumph, and shrink

From the stroke of her wounded wing? [10]

There is a literal movement here from the spirit of the Pilgrim Fathers to their modern-day slave-hunting counterparts. This section highlights the profound attack on Mayflower mythology that constitutes ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’. This negative portrayal is conspicuously at odds with the celebratory treatment of the Pilgrim Fathers by Browning’s most famous literary predecessor: Felicia Hemans.

Browning was conscious of her status as a leading national poet in the same tradition of Hemans; her poem ‘Stanzas on the Death of Mrs. Hemans’ (1838) paid tribute to her most famous literary forbear. [11] However, whilst Browning wrote a celebrative lament on the death of Hemans, her poem ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ makes distinct use of the Pilgrim Fathers narrative that essentially reads as the antithesis of the praiseworthy treatment Hemans provides in ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’. Indeed, in many ways Browning’s poem is an inversion of Hemans’ work: it censures rather than praises the Pilgrim Fathers, and is set in the present rather than the past. Similarly, it considers the ends of a journey rather than the beginning of an origin myth, whilst speaking to a history of injustice rather than a history of freedom. Finally, it mocks rather than celebrates the religiosity of the United States. Moreover, the lexicon and vocabulary of ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ is ironically inverted in ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’. In Hemans’ poem, the ‘Breaking waves dashed high/On a stern and rock-bound coast’ whilst in Browning’s work the slave woman laments that ‘The clouds are breaking on my brain’ as she ‘floated along, as if I should die/ Of liberty’s exquisite pain’.[12] Ultimately for Hemans, it is the ‘Freedom to worship God’ that drives the Pilgrims in their journey, whilst the runaway slave curses the spirits of the Pilgrims Fathers ‘blessed in freedom’s evermore’ whist she is trapped in a life of bondage.

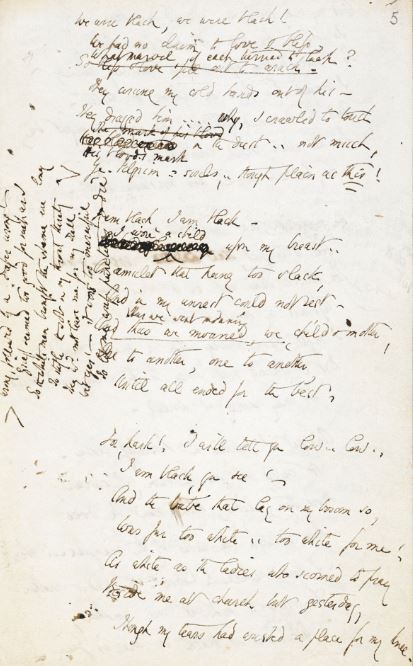

Natural imagery is an important device in both poems, but the implications are wildly different. In Hemans’ poem, the dark natural imagery is used to show the bravery of the poor pilgrims facing a hostile environment: ‘the woods against a stormy sky/ Their giant branches tossed’, whereas Browning’s use of threatening natural imagery is used to convey the hostility of a nation towards people of African descent. As a runaway slave she describes her flight from persecution: ‘The forest’s arms did round us shut /And silence through the trees did run’. Examining the manuscript copy of ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ we can see Browning revise her writing in this section to heighten the sense of claustrophobia and hostility; ‘the forest’s trees did round us shut’ is changed to ‘the forest’s arms did round us shut’ giving the forest a sense of bodily agency threatening to trap the runaway, much like the living descendants of the Pilgrim Fathers.[13] Again there is a similarity with Hemans’ verse where trees ‘their giant branches tossed’ act as if they had a threatening agency of their own. Browning modifies and extends these poetic devices into other, far more controversial areas. From close textual examination is it possible to argue that ‘in ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ is an intertextual engagement with Hemans’ ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ that seeks to write back against a canonical work of Mayflower fiction.

Manuscript draft of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ © The Provost and Fellows of Eton College

It is certain that ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ is a landmark publication in British Mayflower fiction, one that marks an important disjuncture with the celebratory and commemorative narrative towards the Pilgrim Fathers that grew over the nineteenth century. Indeed, it speaks volumes about the attitude of the 1920 tercentenary celebrations that they proudly looked back to poetry of Hemans for an aggrandising example of British Mayflower poetry, but conspicuously ignored the other famous example from the nineteenth-century: the dark, critical, and graphic poetry of Browning’s ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’.

[1] Elizabeth Barret Browning, The Complete Works of Elizabeth Barret Browning, 3, (New York, Thomas Y. Crowell, 1900), p.385.

[2] MS D0800, Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University (Waco, Texas).

[3] Browning, p.160.

[4] Robert Langbaum, The Poetry of Experience (New York: W. Norton & Company, 1957, p.79; M.W. MacCallum, The Dramatic Monologue in the Victorian Period (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1925), p.78.

[5] Cornelia D. J. Pearsall, ‘The Dramatic Monologue’, in The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry ed.by Joseph Bristow, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p.50.

[6] Browning, pp.164-165.

[7] Marjorie Stone, Beverly Taylor, Introduction: ‘”Confirm my voice”: “My sisters,” Poetic Audiences, and the Published Voices of EBB’ in Victorian Poetry, 44.4 (2006) 391-403, (p.391).

[8] Deborah Anna Logan, Fallenness in Victorian Women’s Writing: Marry, Stitch, Die, Or Do Worse (London: University of Missouri Press, 1998), p.180.

[9] Browning, p.90.

[10] Browning, p.168.

[11] Elizabeth Barrett Browning, The Seraphim, and other Poems (London: Saunders and Otley, Conduit Street, 1838), pp.271-275.

[12] Browning, p.170.

[13] BL, Add. MS. 60573, f.3