By 1916 the entry of the United States into the First World War was considered a vital step in securing an Allied victory against Germany. However, for the first two years of the war diplomacy between Britain and America had been marked by uncertainty. Woodrow Wilson had publicly declared America’s policy of neutrality shortly after the outbreak of hostilities between the European powers. In early 1915 Wilson explained America’s policy, ‘The basis of neutrality, gentlemen, is not indifference; it is not self-interest. The basis of neutrality is sympathy for mankind. It is fairness, it is good will at bottom. It is impartiality of spirit and of judgement.’ American public opinion from 1914-1916 also strongly favoured neutrality. Britain’s diplomatic efforts were therefore focused on finding a way to break this impasse and convince a reluctant United States help end the deadlock on the Western Front.

The war of diplomacy was fought on many fronts: one of the first actions Britain took in the war was to cut German telegraph lines to the United States. Moreover, aided by a common language, British propaganda sought to remind Americans of their common values and emphasise the threat of German militarism. Unofficially, the United States had been providing financial assistance to the Allied cause, and in April of 1917 America did enter the conflict, with Wilson describing military action by the United States as “a war to make the world safe for democracy.” Whilst the German submarine blockade of Britain sinking American ships was the immediate pretext for the United States’ entry into the war, there were further economic, political, and idealistic reasons. Nonetheless, Britain was eager to capitalise on an important propaganda victory and sought to publicise Anglo-American co-operation. As a fitting symbol of historical links, the voyage of Mayflower had an important role to play.

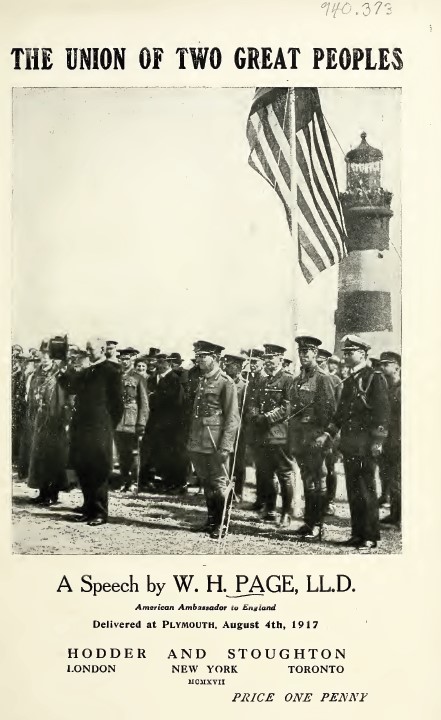

The mayflower was an immediate point of reference for newspapers reporting on the entry of the United States into the war. In July of 1917 The Times reported that ‘[t]he landing of the American troops the other day, although we knew of very little about it, was one of the most significant epochs that has occurred since the departure of the Pilgrim Fathers on board the Mayflower’. These links were further developed with the visit of American Ambassador Walter Page (1855-1918) to Plymouth on 4 August 1917. A Southerner proud of his British roots, Page was known for favouring America’s entry into the war and his belief that Britain was fighting for democracy. Page delivered a speech entitled ‘The Union of Two Great Peoples’ which put the Mayflower story at the heart of wartime Anglo-American relations:

The Mayflower sailed from here nearly three hundred years ago with its precious freight. There have come back American warships, no doubt with the descendants of those same men, and on the soil of our gallant Ally across the Channel there are already landed American troops to join yours.

It was the Pilgrim Fathers, according to Page, ‘who sailed away to carry your ideas of freedom into the New World. We bring back that same idea of freedom for the relief of the imperilled freedom of the world’. The Telegraph commented that ‘[t]he Pilgrims have returned, some in body but millions more in spirit, to the birthplace of American freedom’, whilst The Times reported that ‘the spirit which the Mayflower carried westward is to-day carried eastward’. As Robert Tucker has commented, Britain ‘had been adept in exploiting American sympathy and in turning it into substantive support for the Allied cause’. The narrative of the Pilgrim Fathers was put to full use in securing this relationship.

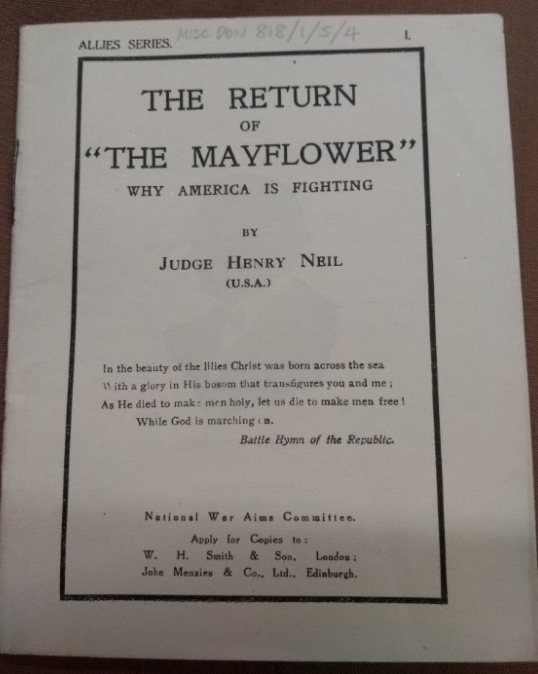

The powerful symbolism of the Mayflower story was noted by Britain’s National War Aims Committee (NWAC), a parliamentary, cross-party organisation established in July 1917 to combat perceived civilian war-weariness. The Committee’s express aim was to ‘strengthen national morale and consolidate the national war aims as outlined by the executive government and endorsed by the great majority of the people’. The NWAC later published The Return of “The Mayflower”: Why America is Fighting (1918), the first in the ‘Allies Series’ of pamphlets focusing on strengthening sentiment between the Allied nations, with particular emphasis on Anglo-American relations.

Written by ‘Judge’ Henry Neil (1863-1939), an American author, educator, and social reformer from Chicago The Return of “The Mayflower” begins with a dramatic account of a 1917 Atlantic crossing: ‘We were then in the danger zone. It was that week when the U-boats sank the largest number of ships. All of us were anxious, nervous, constantly on the lookout’. After defending America’s entry into war as an attempt to ‘extend the right of self-government to others’ Neil makes extensive and emotive use of the Mayflower narrative:

Less than three hundred years ago The Mayflower took the liberty-loving Pilgrim Fathers from England to America.

These fearless pioneers, with righteous zeal, sowed the seed of democracy there. It fell on fruitful ground and for centuries blossomed and bloomed and filled the air with the sweet fragrance of freedom.

In this atmosphere a great people grew strong and brave, and ready, when the supreme hour arrived, to join the mother country in the greatest fight for human liberty the world has ever known.

As I watched that torpedo passing by I wondered if this huge ship, speeding on its way from America to the motherland, laden with the defences of freedom and evading every effort to destroy democracy, was not in reality the Mayflower returning home.

The use of term ‘mother country’ to describe Anglo-American relations stresses an emotional bond between the two nations justified by the Mayflower story. This is all the more significant if we consider the history of popular American Anglophobia which impacted upon Anglo-American relations in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century. The stress Neil places on a maternal relationship between Britain and America seems calculated to counter these concerns with an appeal to common heritage. Neil’s use of romanticised language is also reminiscent well-known Mayflower poetry, such as Wordsworth’s three sonnet sequence ‘Aspects of Christianity in America, The Pilgrim Fathers’ (1842). Neil praises the ‘liberty-loving Pilgrim Fathers’ who with ‘righteous zeal, sowed the seed of democracy’ in fertile American soil. In a similar vein Wordsworth celebrates the ‘Self-will’ and ‘sovereign countenance’ of the independent-minded Puritan emigrants. In Neil’s words, a ‘supreme hour’ has now arrived, and the spirit of independence embodied by the Pilgrim Fathers has returned to play a part ‘in the greatest fight for human liberty the world has ever known’.

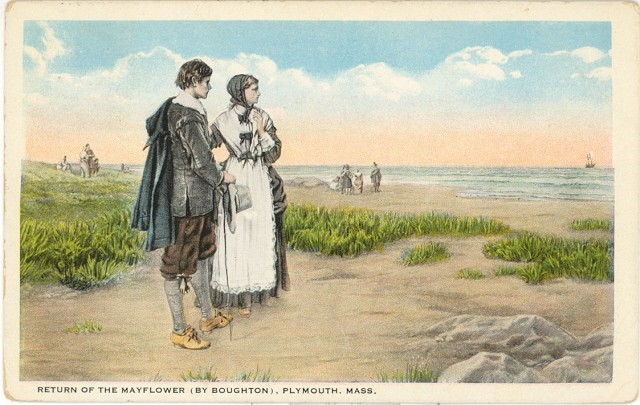

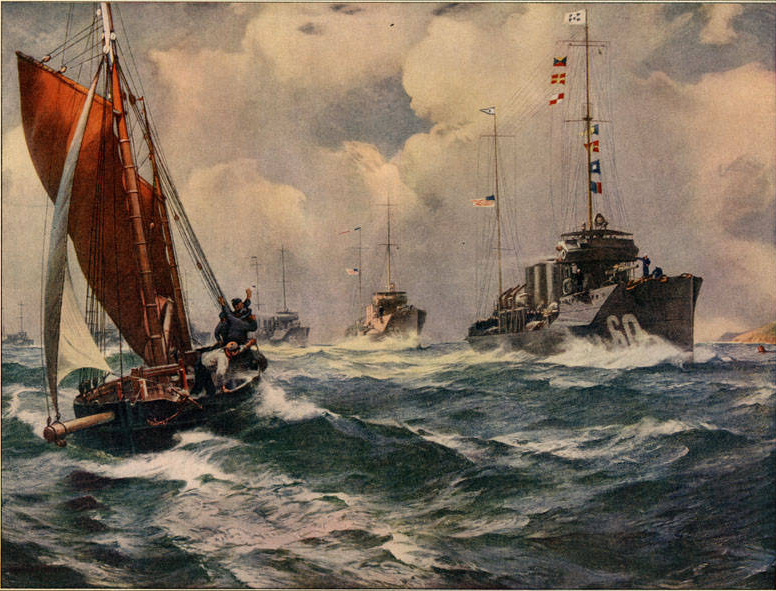

The phrase ‘The return of the Mayflower’ was a familiar expression before its rise to prominence during the First World War. In 1907 the children’s magazine The Young Idea noted that ‘“The Return of the Mayflower” is a favourite subject with painters and poets, because not one of the colonists returned with her’, referring to the 1621 return voyage to England. Indeed, the Return of the Mayflower is the title of a well-known 1871 painting by George Henry Boughton (1833-1905). In 1904 The Perry Magazine summarized Boughton’s work: ‘[i]n his pictures of the Puritans he shows us the most loveable and attractive side of their nature; he gives us in his paintings the sadness of their hard lives and also the sweetness of their faith and fidelity towards one another in the most trying conditions’. This form of sentimentality and emotional resonance is often found in ‘Mayflower culture’ which perhaps helps to explain its popular use during WWI. Boughton’s works were well-known, and ‘The Return of the Mayflower’ was used on postcards for tourists visiting Plymouth, Massachusetts (see image 3). After the end of the First World War Franklin D. Roosevelt, acting as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, commissioned a painting entitled The Return of the Mayflower (1919), by Bernard F. Gribble (1872-1962). The painting depicts the first U.S. destroyer squadron to arrive at the British naval base located in Queenstown (present-day Cobh) on the Southern Coast of Ireland. During Roosevelt’s WWII presidency Gribble’s painting hung in the Oval Office. In this way, ‘The Return of the Mayflower’ came to symbolise successful British and American co-operation in the First World War, and help set the stage for a century of close political ties between the two nations.

IF THIS PHOLOSAFIE OF FEEDOM AN DEMOCRACY COULD BE SHARED AN BELIVED BY EVERYONE THEN THE COMUNIST WAYS OF DICTATIORS AN SOME OF THE THIRD WORLD COUNTRIES WOULD SEACE TO EXIST.

IF THIS PHOLOSAFIE OF FEEDOM AN DEMOCRACY COULD BE SHARED AN BELIVED BY EVERYONE THEN THE COMUNIST WAYS OF DICTATIORS AN SOME OF THE THIRD WORLD COUNTRIES WOULD SEACE TO EXIST. An THE WORLD WOULD BE SO MUCH BETTER.