Memories of the Mayflower in Britain have taken many forms – from paintings and novels to poems and plays. One of the rarer but more long-lasting methods of commemoration are statues and monuments. Dotted around the urban landscape, these structures reflect a lot about what British society – both local and national – thought, at a certain time, was important about the past. Today, these can seem like simple curated objects: through their symbolism and accompanying plaques they tell the story of their makers. But, if we dig down a bit deeper into the documents and local press of the period, we can often find a different angle – and, in this case, one that suggests the Pilgrim Fathers could have both positive and negative meanings to local people.

The most impressive of all the Mayflower monuments (pictured below) was put up in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1889. Formerly known as the Pilgrim Monument but today the National Monument to the Forefathers, it was fashioned from solid granite and is a massive 25 metres tall. ‘Faith’ stands in the middle, clutching a bible and pointing to the heavens, surrounded by figures representing Morality, Law, Liberty and Education. This built evocation of Mayflower mania, coming at a time when interest in the Pilgrim Fathers was growing on both sides of the Atlantic, seems to have started the trend for monuments. Plymouth had the first in Britain: a simple granite block carved ‘Mayflower 1620’ and set into the ground near the supposed ‘Mayflower Steps’ once trod by the Pilgrims.

Monument to the Forefathers – Kparsells2 (2016) – CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Southampton, in Hampshire, could also stake a claim to Mayflower importance as one of the ports from whence the Mayflower sailed. Their own effort of commemorating the Pilgrim Fathers in 1913 was not quite as grand as the Monument to the Forefathers, but it was a significant step beyond Plymouth’s. It was first mooted in 1909 by Fossey John Cobb Hearnshaw. A Professor of History at Southampton’s University College since 1900, he had actually been born in Birmingham. But, from his first years in Southampton, he threw himself into building up the culture of the town, setting up exhibitions of ‘relics’ from ‘old Southampton’, giving talks about local history to schoolchildren and adults alike, and founding the Southampton Record Society. In his books on Southampton’s history, he celebrated how the town had contributed to the progress of Britain and her Empire – all the way from the Saxons to the present day. For Hearnshaw, history was more than just a profession or a pleasure: it was a way to create locally patriotic citizens.

Hearnshaw was a medieval specialist, and keen to show his period was relevant to the present. The ‘Anglo Saxons’, he argued, had begun the process that had led to the civil and religious liberties that modern Britons enjoyed. Even more impressive than this was how these ideals had spread to ‘the other great Anglo-Saxon federation’: the USA. Shaping that sort of narrative meant that Hearnshaw could link Britain to the USA at a time when imperialists were asking just what the model for the Empire should be. Enter, then, the Pilgrim Fathers: the men who literally transported those ideals from one land to the other. As he put it, in a 1910 book the Mayflower voyage and its connection to Southampton: ‘To have given shelter to the Mayflower for a fortnight during the course of that memorable voyage is an honour of which Southampton has good reason to be proud.’

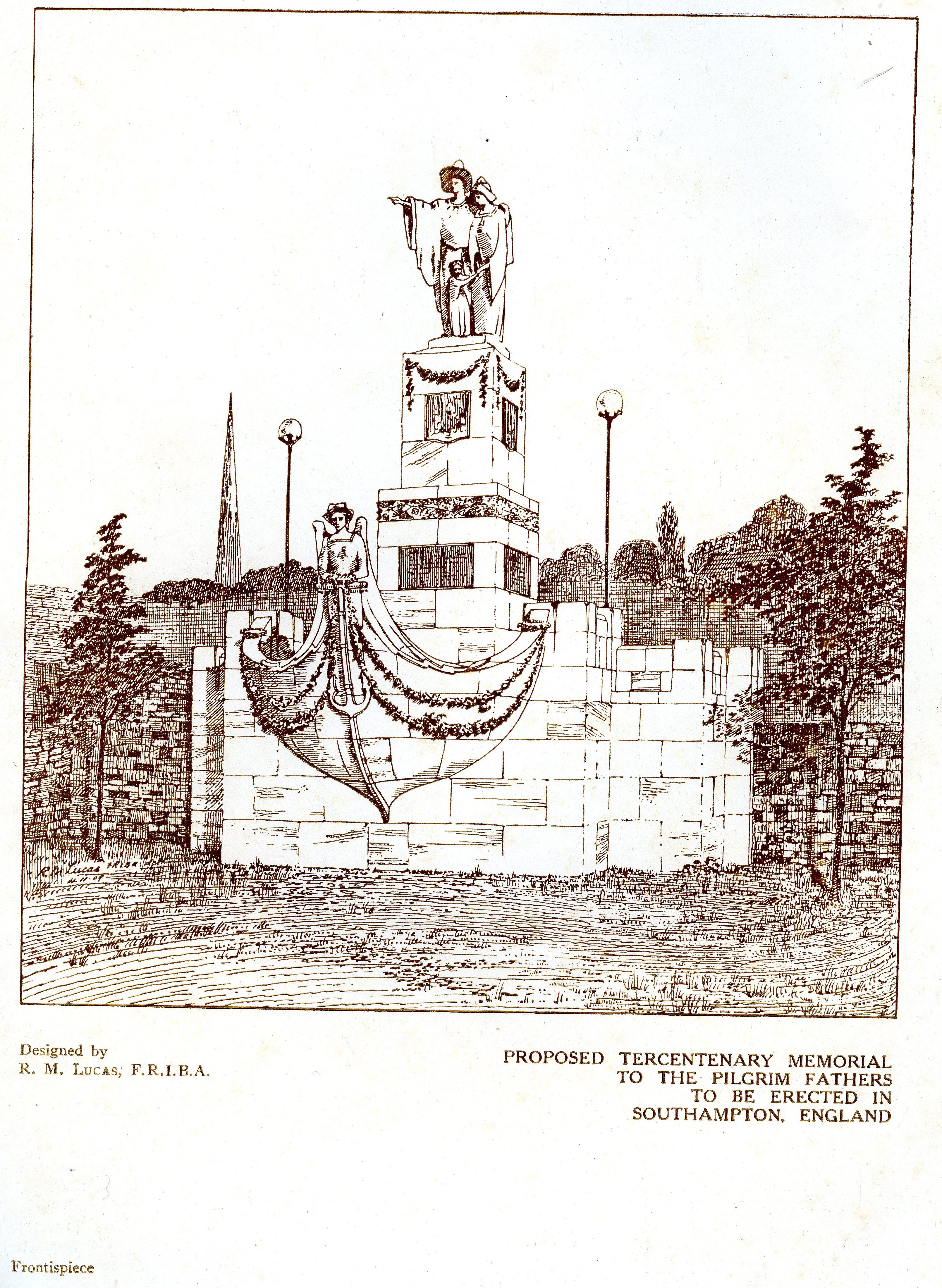

Original design for the Memorial – F.J.C. Hearnshaw, The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers especially showing their connection with Southampton (Southampton, 1910).

Already, in early 1909, a civic committee had been formed – headed by the Mayor but with Hearnshaw the driving force – to raise the necessary money. In a circular that went to newspapers across Britain and the USA too, the committee stressed that anyone – ‘irrespective of nationality or creed’ could contribute in this acknowledgement of ‘pride’ in the ‘early colonial ventures of their ancestors’. Not everyone in Southampton was happy about this civic campaign, however. Charles Cooksey, another local historian, was unconvinced. He saw the memorial as a ‘vanity’ project for both Hearnshaw and the town council, and the Pilgrim Fathers a load of unpatriotic and ‘unscrupulous murdering rascals’ who went on to oppress people of different faiths to their own – including Catholics like him. He wrote letter after letter to the local press during the campaign, and was joined by others too – usually writing under pseudonym’s – who not only complained about the ‘bigotry’ of the Fathers, but the cost of the monument too. As one Southampton man put it, local people ‘already had enough to do to pay high rents and taxes’ without worrying about the long-gone Pilgrims.

Money was slow to come in; one of the secretaries for the committee noted that there were ‘many good wishes’, such as those from American ambassadors and Massachusetts Governors, but ‘very little cash’ in general. In the end the grand designs had to be somewhat down-scaled. But the monument – costing £600 at the time – was still an evocative piece of work, and still, arguably, the most substantial in Britain. Standing on the Western Esplanade, chosen to be ‘as near as possible’ to ‘the actual point of departure’, it consists of a Portland stone square column which rises fifty feet from a stepped base, tapering slightly at the end. A white and gold glass mosaic cupola, supported by eight columns, sits on top, crowned by a copper Mayflower weather-vane. On every second column there are carved corbels: three female heads, representing Faith, Hope and Charity; and the prow of a ship, facing the sea. Original inscriptions were to the ‘little company of Pilgrim Fathers who were destined to be the founders of the New England states of America’, and individual pilgrims such as Alden and William Brewster.

Southampton’s Pilgrim Father’s Memorial – Copyright: Southampton City Council

In August 1913 a ceremony was held to commemorate the erection of the memorial. A brief religious service by the Lord Bishop of Winchester and local Congregationalist Reverend G.S.S. Saunders was accompanied by singing by the Free Church Choral Union and music from the Borough Police Band. Walter Hines Page, the American Ambassador, gave the primary address and waxed lyrical about the Pilgrims – ‘dauntless adventurers’ that ‘went in search of God and not gold’. Above all his speech celebrated the shared heritage between the two nations: ‘in spite of the fusion of races and of the great contributions of other nations… the United States is yet English-led and English-ruled.’ The ceremony ended with the playing of both nation’s national anthems – a prophetic sign of the trying times shortly to come.

The Memorial today – taken by author (2018)

More about the Pilgrim Father’s Memorial, and other commemorations of the voyage in Southampton, can be found in Tom Hulme, ‘Memories of the Mayflower in Southampton’, Hampshire Papers (forthcoming 2020).

This blog draws particularly on: Reba Soffer, History, Historians, and Conservatism in Britain and America: From the Great War to Thatcher and Reagan (Oxford, 2009), 51-85; F.J.C. Hearnshaw, The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers especially showing their connection with Southampton (Southampton, 1910); and many articles from the Southern Echo between 1909 and 1913.