Historical pageants were, at one time, the most popular form of engagement with the past in Britain. Bursting onto the social stage in 1905, they took place across the country and the Empire, from the smallest villages to the largest cities. Amateur casts up to 10,000 people – and that is not a typo – were brought together by ingenious ‘pageant-masters’ to perform their local history, and audiences of up to 100,000 packed themselves into outdoor arenas and fields to spectate. In the early days of the ‘pageantitis’ pandemic, the storyline of pageants usually began in the dim and distant past of ancient Celtic Britain, before the arrival of the Romans heralded the beginnings of civilisation. Following episodes cycled through the conquering Saxons and Normans, then the different monarchical reigns from Tudor to Elizabethan. Usually ending with good old Queen Bess, these romantic re-enactments told a story of local and national progress: the setting of historical foundations for great power in the present.

Many of the foundational aspects of the pageant movement had antecedents: the ritualistic parades of the Lord Mayor’s Show in London, the mystery plays of the medieval era, Shakespeare’s own historical romances, or long-standing re-enactments further afield like the passion play of Oberammergau. And the historical spectacular has echoed into the more recent past, too; eagle-eyed observers may notice, for example, the pageant-esque aspects of Danny Boyle’s great opening ceremony for the Olympics in 2012. But there is no doubt that the movement had seen its heyday by the late 1950s, replaced by other forms of entertainment and historical consumption – from the less expensive ‘son et lumiere’ performances to the sedentary sub-urbanity of the television. Fortunately for the historian, these one-off events have left behind a wealth of material that we can use to reconstruct the hopes, desires and anxieties of both the people who put on the pageant, and the eager volunteers who performed or watched.

Many of the episodes depicted in pageants were distinctly parochial and inward-looking: the granting of medieval charters, the visits of Kings and Queens, or the local experience of bigger events like wars or the dissolution of the monasteries. By the early twentieth century, there is no doubt that the Pilgrims and the story of the Mayflower were an important part of Britain’s historical culture, and a tale that was told in novels, poetry and monuments. But the central element of the Mayflower mythology, the emigration of an oppressed group, raises a question: how could the leaving of the Pilgrims be securely embedded in a form of historical reproduction that stressed continuity in national growth? From the Edwardian era of the movement until at least the early 1950s, this was a question that pageant-masters in Britain were able to answer – though not always in the same way.

The earliest attempt to depict the Pilgrims in a British pageant came with the gigantic Pageant of London staged as part of the Festival of Empire in 1911. A whopping 15,000 amateur performers took part in portraying the history of London and the British Empire to a total audience of over 1 million people – probably the biggest pageant ever staged. In this defensive celebration of Britain’s colonial power, the Pilgrims feature just briefly: leaving Plymouth harbour in 1620 as an example of the movement of English spirit all across the world. Significantly, ‘American visitors’ helped put on the episode. In the Pageant of London, then, the Pilgrims were a way to portray not just imperial expansion in the past but growing rapprochement between world powers in the present.

It was not until 1920 that whole pageants about the Pilgrims were performed in Britain. That year, of course, was the great 300th anniversary of the voyage, and hundreds of thousands of people would have seen the Pilgrims come alive before their very eyes. Probably the most inventive was ‘John Alden’s Choice’, which took place in Southampton – the claimed hometown of the eponymous protagonist. About 440 performers gathered on the town’s west quay in front of a specially erected grandstand (and a stones throw away from the Pilgrim Father’s Memorial, put up in 1913). The beginning of this pageant showed John Alden in Southampton and the leaving of the Mayflower, using a mix of farce and educational entertainment. But the main focus of the pageant was actually on the future: the ‘choice’ of the title was whether Alden would leave his home if he saw the destiny of the country to which he would travel. Shown through the mystical magic of a ‘gypsy’, he saw: the declaration of peace between the Pilgrims and the Indians; the Boston Tea Party in 1773 and the American Revolution in 1789, and thus the breaking away of the New England colonies; and Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863. It was only when he saw the ‘return of the Mayflower’ from the USA in 1917 to help the Allies win the war that he decided he must leave: the future of the world depended on it. In the shadow of the First World War, the Pilgrims were put to work as an example of the Anglo-American unity that would ensure freedom and democracy in turbulent times.

John Alden’s Choice Pageant (Britannia and America), Southampton (1920) – copyright Southampton City Archives, P236_7025

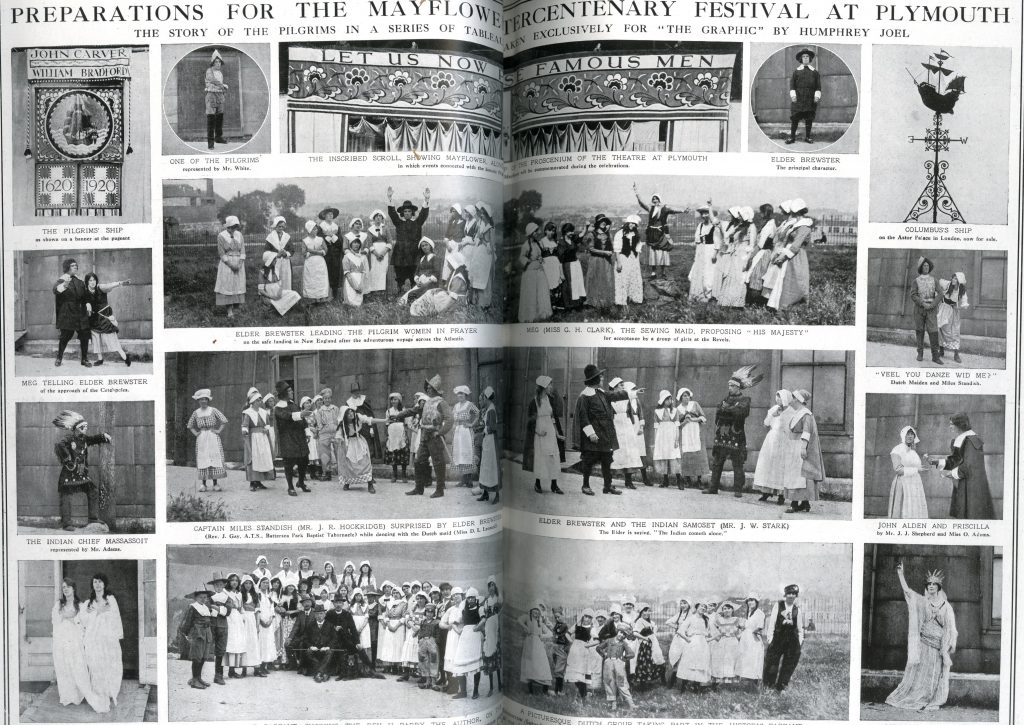

If John Alden’s Choice was the most inventive, the ‘Historical Mayflower Pageant’ written by the Reverend Hugh Parry was by far the most successful. Parry was the minister of Harecourt Chapel in London, and a keen author of nonconformist pageants and plays. His Mayflower pageant, commissioned by the Mayflower Council of England, was first performed by a cast of 300 in Plymouth (and seen by as many as 30-40,000 people). Over that summer, and into 1921 and beyond, Parry’s pageant was performed in many other towns and cities: Sheffield, Preston, London, Huddersfield to name a few. Like Southampton’s pageant, there was an element of the present – John Alden, again, saw a vision of the American entry to the First World War (though, in this case, in a crystal ball gifted to him by Native Americans). But much of the pageant stuck more faithfully to the history of the Pilgrims, from events in Scrooby in 1608 to the Netherlands, the setting off of the voyage, and scenes in the New World. Though Parry drew on the romance of Henry Longfellow for much of the drama, this was still a story steeped in religious memory: a way for Congregationalists and other nonconformist denominations to celebrate one origin of their beliefs.

Photos from Hugh Parry’s Mayflower Pageant in The Graphic (4th September 1920), 9. Copyright Mary Evans Picture Library

Hugh Parry’s pageant was still occasionally performed in the 1930s by religious congregations. But, into these mid-twentieth century decades, the story of the Pilgrims again became just one episode of many. In Southampton, Plymouth and Boston, places that arguably played only a minor role in the story of the Mayflower but had nonetheless inserted themselves front and centre in public memory, there was usually at least one Pilgrim-related episode. As examples: in the ‘Pageant of Hampton’ in 1929, the finale consisted of ‘The Spirit of Hampton’ being hailed as Queen of Ports and presented with a model of the Mayflower and one of a modern steam liner, too; in the ‘Pageant of Boston’ in 1951, the Pilgrims were seen being apprehended before their failed escape attempt from the Lincolnshire coast in 1607; and in the ‘Pageant of Plymouth Hoe’ in 1953, one episode showed the Pilgrims enjoying ‘the kindness of Plymouth’ before leaving in 1620. A loose sense of religious identity was still present in these pageants and episodes, but the exploits of the Pilgrims were being shown more as a symbol of each town’s contribution to the unfolding of history than as a pious remembrance of their trials and tribulations in the Old and New World. In this way, we might argue, they reflect the more popular usage of the Pilgrims after the religious outburst of the early 20th century: a move towards the Mayflower as a form ‘local heritage’ for everyone that has continued to the present day.

If you would like to learn more about the Mayflower pageants described in this blog, and indeed the many others that were staged, you can use the ‘Historical Reenactment’ tag on our interactive map. Who knows – perhaps a Mayflower pageant took place in your town? If you know of anymore recent Pilgrim Pageants, we’d love to hear from you too. If you are interested in the historical pageant movement, this brilliant project website should be your first port of call!