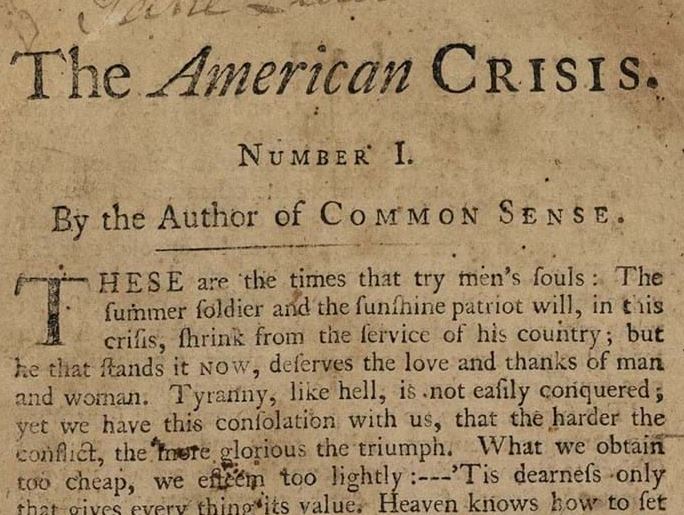

H.T. Dickinson comments that ‘The American Revolution was the first great modern revolution and it has arguably been the most permanent, successful and widely admired’.[1] The results of this major event led to ‘the oldest surviving written constitution in the world’, and ‘a remarkably successful liberal regime’ that contrasted with the established political systems of eighteenth-century Europe.[2] Unsurprisingly such an influential event has received attention from generations of American scholars and historians. However, not as many historians have explored the British perspective on what was memorably termed by Thomas Paine ‘The American Crisis’. Britain was far from united in supporting the war with the American colonies – and indeed, for some political commentators, the story of the Mayflower provided a historical justification for American secession.

Detail from Paine’s The American Crisis: a pamphlet series published from 1776 to 1783 during the American Revolution. Public Domain.

Paine was a case in point; an enthusiastic proponent of American Revolution, he was born in Norfolk, England. His attitude and was representative of the considerable British sympathy for American independence. Paine’s publications such as Common Sense (1775-1776) and The American Crisis (1776-1783) celebrated the American cause as an example of a universal movement towards freedom:

The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances hath, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all Lovers of Mankind are affected, and in the Event of which, their Affections are interested.[3]

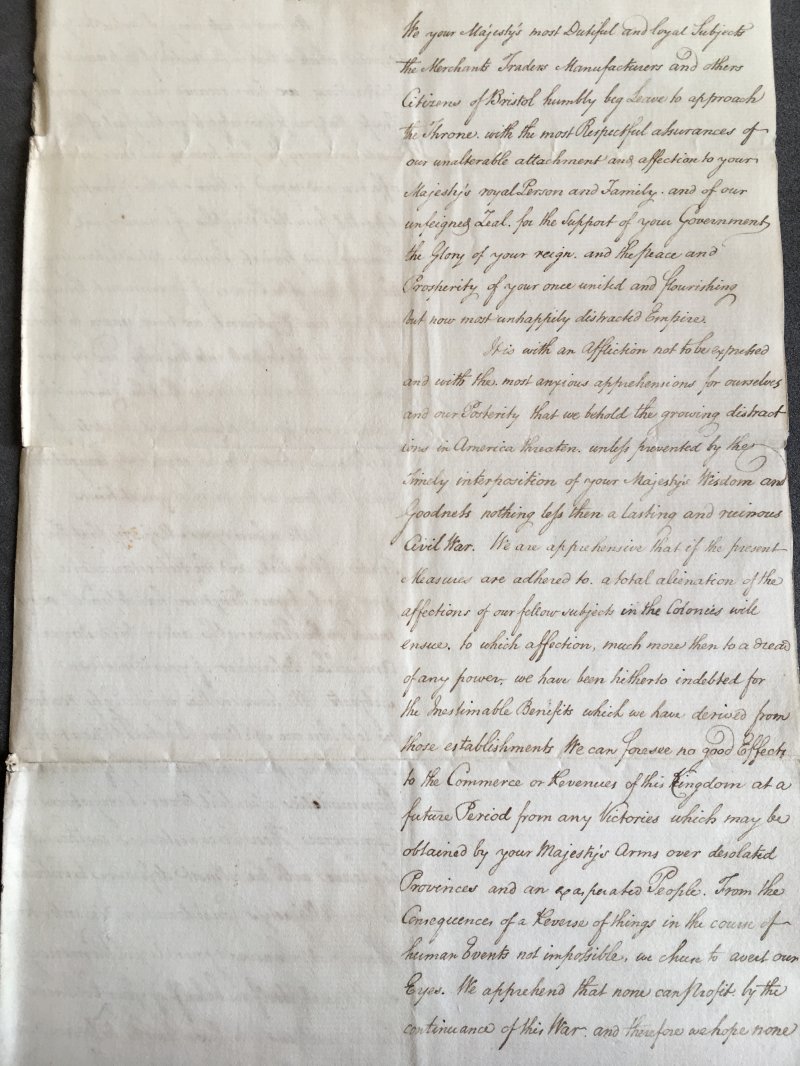

We know from many popular petitions to Parliament from towns such as Newcastle and Bristol that there was large-scale public discontent with the policy of the British government.

A petition from the Merchants, Traders, Manufacturers and other citizens of Bristol to George III; c.1775 Nottingham University Archives.

‘The American Crisis’ was well reported in the British press. The Stamp Act was passed in 1765 and provoked riots in America, the Boston Tea Party took place in 1773, and the infamous ‘shot heard round the world’ (the opening shot of the Battle of Concord) was fired in 1775, seen by many to mark the start of the American Revolutionary War. The press was frequently critical of the British military and government. Indeed, regarding the Battle of Conrad, The Salisbury and Winchester Journal reported on money collected ‘to the relief of the widows, orphans, and aged parents of our beloved American fellow-subjects, who, faithful to the character of Englishmen, preferring death to slavery, were inhumanly murdered by the King’s troops at or near Lexington and Concord in the province of Massachusetts’.[4] The paper further bemoaned that ‘attempting to compel the Americans by force or arms’ would mean ‘no hope of further reconciliation was left’.[5]

As James E. Bradley comments, regional newspapers diverged strongly from the official government position and much of the London press:

By the mid-1770s, in every corner of England one could find competing papers taking an opposite stance on the American conflict […] Every region saw this war of newspaper opinion: from Hampshire west to Gloucester and Bristol, from the far north-west to East Anglia, to the south-east, one can find papers that took a consistently pro-American viewpoint, with editors regularly at odds with the government.[6]

The voice of opposition to the government and support for the colonists was strong. Moreover, as Bradley points out, regional opposition newspapers from the revolutionary period have been largely neglected by historians.[7]

Scholarship has not yet examined the British use of the Mayflower myth to lend support to the American colonists. Of course, this was before the name ‘Mayflower’ was associated with the settlement of New Plymouth by Brownist separatists, which was a later, nineteenth-century development. Despite this, the story of colony itself still had a vital role to play. Opposition papers used the narrative as early as the 1760s to lend support to the American colonists.

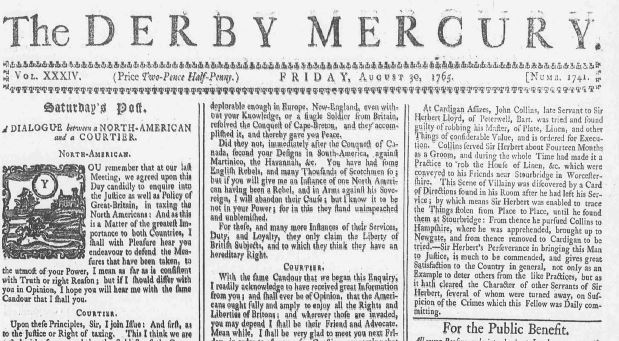

‘A DIALOGUE between a North American and a Courtier’ published in the Gazetteer and the Derby Mercury was one such example of the New Plymouth narrative used as an argument in favour of equitable treatment for the North American colonies.[8] Staged as a dialogue between a ‘North American’ and a ‘Courtier’ the conversation is positioned to show the American participant as more reasonable, virtuous, and honest. Dialogue-based exchanges were a popular form of political discussion in the eighteenth-century, with Hannah More’s 1793 Village Politics becoming a famous post-French revolutionary example.[9] Like More’s work, class plays an important role in ‘A DIALOGUE between a North American and a Courtier’; the establishment position of the ‘Courtier’ is at odds with the common-sense arguments given by a ‘North American’. The example of the poor, persecuted, emigrants who settled New Plymouth ties into this class inflection.

North American.

[…]

But let me ask you, was it from a principle of the great love to us North Americans, that you undertook those expeditions, or for your own sakes, to serve yourselves, and to extend your trade? For you very well know, that with the loss of the colonies you would lose a great part of your power too. This then was the great motive of your attention therein.

As to your being a tender parent, nursing infancy, protecting in youth, and rearing to manhood, it is really very oratorical, and tickles one’s ear, but carries not the least truth with it; since every body knows that our most worthy ancestors of New England were persecuted in this country, and in 1620 embarked at Plymouth for North America, without any protection succour from this tender parent; they landed in a country which was one vast wilderness, peopled by fierce savages, with whom they traded, they fought, and whom they conquered.

[…]

Courtier.

With the same candour that we began this enquiry, I readily acknowledge to have received great information from you; and shall ever be of the opinion, that the Americans ought fully and amply enjoy all the rights and liberties of Britons; and wherever those are invaded, you may depend I shall be their friend and advocate. Meanwhile, I shall be very glad to meet you next Friday, in order to ask you a few questions concerning that country, and the taxes imposed on it.

Written under the pseudonym of ‘MARCUS AURELIUS’, the Stoic ‘enlightened’ Roman emperor, the article contains a rational argument in favour of equal treatment of the North American colonies. Whilst the ‘Courtier’ claims that England is the ‘tender parent’ of the North American colonies, thereby asserting a paternal form of ownership, the ‘North American’ retorts with the assertion that the assertion ‘carries not the least truth with it; since every body knows that our most worthy ancestors of New England were persecuted in this country, and in 1620 embarked at Plymouth for North America, without any protection succour from this tender parent’. The claims to independence from England, and therefore royal authority, is bolstered by the reference to ‘persecuted’ settlers who were forced to leave their homeland due to governmental intolerance. ‘A DIALOGUE between a North American and a Courtier’ is an important early example of the New Plymouth narrative in British political culture.

Later in the 1770s The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser continued its support of American independence. An article by ‘A Plain Citizen’ makes an argument in favour of greater autonomy for the North American colonies that is centred on the settlement of New Plymouth. In part, the argument is based on ‘natural right’ theory, an Enlightenment concept of ‘government by consent’ developing from the work of Hugo Grotius, expanded by John Locke, and finding most popular expression in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Compact (1762). Whilst the article is significant for its connection of New Plymouth to revolutionary eighteenth-century political ideas, we also see an emotive component in the retelling of the settlement narrative consistent with later variations:

To form a proper judgment of the proceedings of the Bostonians, it is absolutely necessary to be acquainted with the original constitution of that country. We know, Sir, that an honest English Parliament has declared, that when a King breaks the original contracts, he immediately forfeits his right to the Crown; and what us this original contract but the fundamental principles of the constitution, which, if any power on earth dares to invade, it is not only lawful, by the duty of every Englishman to resist such power, and defend his right. And is this privilege, this duty, confined to England? Surely no; it extends to every kingdom, every state, every province inhabited by rational beings in the whole world. It is not a law, a right of England only, it is a law of Nature, equally binding on all; it is a right bestowed by the great creator himself, which it would be sacrilege to part with.

Let us now take a short view of the first settlement of New-England, whose capital (Boston) is the metropolis of the English settlements in America. In the latter end of the reign of James the First, the people, then called Puritans, were most cruelly persecuted by the High Commission, and other illegal Courts; and great numbers were obliged to retire to Holland and Germany; among these a congregation settled at Leyden, but not liking their situation they prevailed, by their friends at home, or King James’s Secretary, to desire his Majesty’s consent for transporting themselves to America; to which he readily consented: then getting a kind of licence from Capt. Gosnold (who had some time before obtained a grant of certain lands from North latitude 38 to 45 along the coast, and as much within land) several of them sold their estates, and made a common Bank for a fund to carry them on the great undertaking, and with the assistance of some private merchants, they purchased a small ship of 180 tons, and coming to Plymouth were joined by some of their friends, making in all about 120 persons, besides 30 seamen: these set sail about the 6th of September 1620, and after a dangerous voyage of more than two months fell in with Cape Cod. They were no sooner ashore, but considering that they were not within the limits of Gosnold’s grant, and that they had no right to take possession of any man’s land without his consent, they treated with the Cacique, or Lord of the place, and his chief men, for part of the country to settle in; to which, for a valuable consideration, the natives freely consented. So that these adventures became possessed of what they bargained for in their own right. And these lands, purchased by them, were situated at a great distance North East from those granted to Gosnold; they therefore, held them, by virtue of the valuable consideration they had paid those who alone had a legal right to dispose them; namely, the real owners, and not by Gosnold’d grant, or any license from King James. – And thus, Sir, was the first settlement made in the province of New England by a company of poor, persecuted, private adventures, without any expense to, or assistance from the Crown. These men were not transports, rebels, or traitors; they were not banished their country for evil practices; they were a set of sober conscientious men, willing to endure any hardship rather than act contrary to the dictates of conscience.

Thus we see a the first adventures settled without any assistance from the Crown of England, and that they purchased their possession of the legal owners, but thought proper to put themselves under the protection of the English sovereign, on condition of enjoying the rights of Englishmen; one of which is, that they cannot be dispossessed of their property without their consent, expressed by themselves or representatives (and here as the original New England contract). […]

If any man, or body of men, attempt to rob me of my property or rights, I am justiced, by laws of Nature and self-preservation, to resist such attempt and to project my right; and have not the Bostonians the same privilege? This Sir, is a law of Nature, not of any particular country, it is equally binding in every part of the globe.[9]

The claim that the inhabitants ‘cannot be dispossessed of their property without their consent’ evokes developing ideas of popular sovereignty that will ultimately be reflected in the American Declaration of Independence and set the stage for the French Revolution. Indeed, the use of the pseudonym ‘Citizen’ is significant (as opposed to ‘subject’ with the denotation of rule by a sovereign): this was a charged, anti-monarchical term popular with radicals from the 1770s into the early nineteenth-century.[11] In this article, it is the ‘natural rights’ of the separatists that are foregrounded. Indeed, rather than the connectedness of Britain to America, Britain is argued to be a distant and tyrannical society that limits popular sovereignty in favour of centralised arbitrary power. Importantly, there is not only an argument in favour of American autotomy, but also greater self-government in British towns. In this way, the ‘Mayflower’ story is used to portray Britain as an illiberal state, both at home and abroad. There is still an emotive element to the retelling: the separatists are described as ‘most cruelly persecuted by the High Commission, and other illegal Courts’ and as a ‘company of poor, persecuted, private adventurers’. This heightens the sacrifices made by the separatists to obtain their land and the immorality of Britain claiming it as their own territory.

These articles show that the narrative of New Plymouth played an active role in British politics surrounding the American Crisis. Whilst later poets such as Felicia Hemans modified the myth to serve more socially conservative and pro-establishment uses, this was not always the case. In many ways these articles represent the beginnings of the radical dimension of the Mayflower narrative, one which would find expression in the Chartist Mayflower poetry of Ebenezer Elliott and the Fenian verse of John Boyle O’Reilly. The radical, and pro-revolutionary element to the Mayflower myth thus continued to play an active role long into the nineteenth century.

[1] H.T. Dickinson, Britain and the American Revolution (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014), p.1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Thomas Paine, Common Sense: Addressed to the Inhabitants of America (Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1775), p.ii.

[4] Salisbury and Winchester Journal – 12 June, 1775, p.3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] James E. Bradley, ‘The British Public and the American Revolution’ in H.T. Dickinson (ed.) Britain and the American Revolution pp.124-154 (p.153).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, August 17, 1765, p.1; Derby Mercury, 30 August, 1765, p.1.

[9] Hannah More, Village politics. Addressed to all the Mechanics, Journeymen, and Day Labourers, in Great Britain (London: C. Rivington, 1793).

[10] Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, April 15, 1774, pp.1-2.

[11] See for example see the writing of ‘Citizen’ John Thelwall (1764-1834) and Richard ‘Citizen’ Lee (1774-1797).