They could not live by king-made codes and creeds;

They chose the path where every footstep bleeds.

Protesting, not rebelling; scorned and banned;

Through pains and prisons harried from the land

– John Boyle O’Reilly: Poem read at the Dedication of the Monument to the Pilgrim Fathers at Plymouth, Mass., 1 August, 1889.

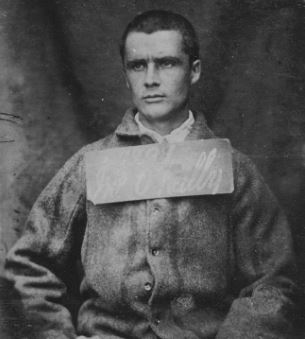

John Boyle O’Reilly as a prisoner in 1866. Public Domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Boyle_O%27Reilly.jpg

On October 12, 1867, the convict ship Hougoumont left Portsmouth, England, bound for the Penal Colony of Western Australia. The last convict ship to ever leave Britain, the Hougoumont arrived laden with 279 prisoners sentenced to transportation. One of those men was John Boyle O’Reilly (1844-1890), part of a group of Irish prisoners who were members of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, also known as the IRB or Fenian Brotherhood. Fearful of another Irish uprising, the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood was persecuted by the British government who saw the movement as an intrinsic threat to their interests in Ireland. As T. W. Moody comments, the Fenians had revolutionary politics at their core: the brotherhood was ‘essentially a physical-force movement which absolutely and from the beginning, repudiated constitutional action […] [m]ore than any other school of nationalism the Fenian movement concentrated on a single aim, independence, and insisted that all other aims were beside the point’.[1]

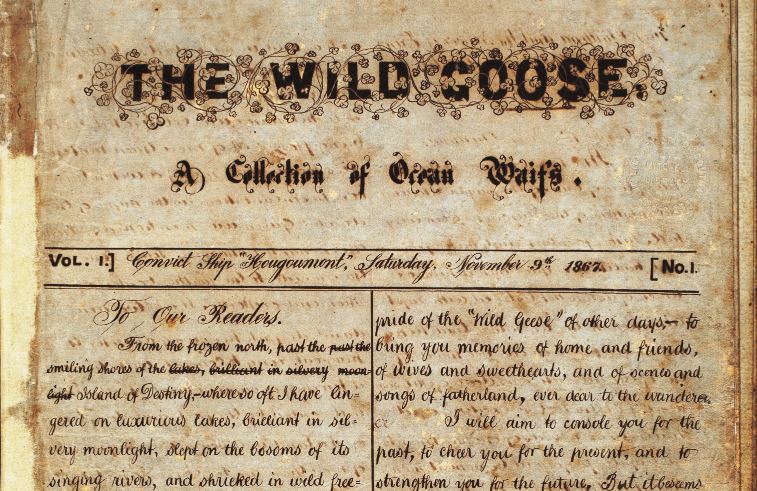

Born in Meath, Ireland, O’Reilly worked as a recruiter for the IRB whilst also serving in the British Army. In 1866 his secret revolutionary activities were discovered by the British authorities and he was charged and convicted of Treason. This carried a death sentence, however, due to his young age (22 yrs) the sentence was later commuted to 20 years penal servitude and transportation to Australia. Ever the writer and propagandist, O’Reilly hand-wrote 7 editions of a newspaper, The Wild Goose on board the Hougoumont to keep-up the morale of his fellow convicts (see figure 1). He found lasting fame, however, for staging an audacious escape from the Penal Colony of Western Australia.

Figure 1: The first edition of John Boyle O’Reilly’s hand-written newspaper produced on-board the convict ship Hougoumont. Public Domain, original owned by Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales MLMSS 1542

Aided by Irish-born priest, Fr. Patrick McCabe and local farmer James Maguire, O’Reilly escaped from the convict colony near the town of Bunbury on the night of 17 February 1869. For two weeks he remained in hiding in the bush and dunes near Australind whilst a huge manhunt was conducted by the British authorities. The Philadelphia Times of June 25, 1881 gave the following dramatic account of O’Reilly’s desperate attempt to escape on-board the US whaling ship Vigilant whilst remaining in hiding:

Next morning he ventured out to sea in this frail craft, which he had made water tight by the use of paper bark. In order to keep his stock of meat from spoiling in the hot sun he let it float in the water, fastened by a rope of paper bark to the stern of the boat. The light craft went rapidly forward under his vigorous rowing, and before night had passed the headland and was on the Indian Ocean… That night on an unknown sea in a mere shell had a strange, weird interest, heightened by the anxious expectations of the seeker for liberty. O’Reilly ceased rowing the next morning, trusting to the northward current to bring him within view of the whale-ship. He suffered a good deal from the blazing rays of the sun and their scorching reflection from the water. To add to his troubles, the meat towing in the water was becoming putrid, and he found that some of the possums and kangaroo rats had been taken by sharks in the night. Toward noon he saw a vessel under sail which he knew must be the Vigilant and his hopes ran high, as she drew so near to the boat that he could hear voices on her deck. He saw a man aloft on the lookout; but there was no answer to the cry from the boat, and the vessel again sailed off, leaving O’Reilly to sadly watch her fade away into the night. He afterward heard from Captain Baker that, strangely enough, the boat was not seen from the ship.[2]

Despite setbacks and a number of close escapes from the authorities, O’Reilly eventually escaped on-board the US whaling ship the Gazelle.

O’Reilly disembarked in Philadelphia in November 1869. Jeffrey Roche recorded the event in the Life of John Boyle O’Reilly: ‘His first act after landing was to make a votive offering to Liberty. He presented himself before the United States District Court and took out his first papers of naturalization’.[3] O’Reilly eventually settled in Boston, where he found work as a reporter on the Boston Pilot. His first major assignment was to cover the 1870 Fenian raid on Quebec and Manitoba, Canada. He would remain associated with the Fenians for the rest of his life, becoming a well-known Irish revolutionary figure in America.

In his obituary Harper’s Weekly magazine offered the following description that provides an idea of his standing:

[He was] easily the most distinguished Irishman in America. He was one of the country’s foremost poets, one of its most influential journalists, an orator of unusual power, and he was endowed with such a gift of friendship as few men are blessed with.[4]

O’Reilly’s status as a leading literary figure with connections to Boston saw him asked to write a poem for the dedication of the national monument to the Pilgrim Fathers in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1889 (see figure 2).[5] This choice of a Catholic Irishman for the role rather than a native of New England was controversial; some commented that O’Reilly ‘had extolled the narrow Puritans and forgotten their intolerance, and […] accused him of having brought the Blarney Stone into conjunction with Plymouth Rock’.[6] However, the poem as well received by many in New England.[7] In keeping with O’Reilly’s revolutionary sentiments regarding Ireland the poem makes strong censure of British power and oppression. The antithesis of British misrule are the Pilgrim Fathers who as émigrés from despotism become the founders of a Utopian ‘kingdom not of kings, but men’.

The poem’s opening foregrounds revolutionary themes and political intent:

The Pilgrim’s Fathers

ONE righteous word for Law—the common will;

One living truth of Faith—God regnant still;

One primal test of Freedom—all combined;

One sacred Revolution—change of mind;

One trust unfailing for the night and need—

The tyrant-flower shall cast the freedom-seed.

So held they firm, the Fathers aye to be,

From Home to Holland, Holland to the sea—

Pilgrims for manhood, in their little ship,

Hope in each heart and prayer on every lip.

They could not live by king-made codes and creeds;

They chose the path where every footstep bleeds.

Protesting, not rebelling; scorned and banned;

Through pains and prisons harried from the land;

Through double exile,—till at last they stand

Apart from all,—unique, unworldly, true,

Selected grain to sow the earth anew;

A winnowed part—a saving remnant they;

Dreamers who work—adventurers who pray!

What vision led them? Can we test their prayers?

Who knows they saw no empire in the West?

The later Puritans sought land and gold,

And all the treasures that the Spaniard told;

What line divides the Pilgrims from the rest? [8]

Written in rhyming pentameter, the opening of the poem makes use of couplets to convey a sense of rhythm and forward movement towards a ‘sacred Revolution’ and ‘freedom’ from ‘king-made codes and creeds’. The second stanza finishes with a volta written in alternate rhyme and divides the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ from ‘later Puritans’ seeking ‘land and gold’ and Spanish ‘treasures’. There is an allusion here to the ‘Black myth’ of Spanish imperial avarice and an echo of Hemans’ well-known settlers unconcerned with ‘Bright jewels of the mine’ or the ‘wealth of the seas’. The stanza concludes by asking the reader ‘what line divides the Pilgrims’ from other colonists? The answer is that these Puritans are exiles fleeing from tyranny:

We know them by the exile that was theirs;

Their justice, faith, and fortitude attest;

And those long years in Holland, when their band

Sought humble living in a stranger’s land.

They saw their England covered with a weed

Of flaunting lordship both in court and creed.

With helpless hands they watched the error grow,

Pride on the top and impotence below;

Indulgent nobles, privileged and strong,

A haughty crew to whom all rights belong;

The bishops arrogant, the courts impure,

The rich conspirators against the poor [9]

O’Reilly’s ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ escape from England which has been ‘covered by a weed’, where the rich ‘are conspirators against the poor’ and ‘indulgent nobles’ claim ‘all rights’ for themselves. England is portrayed as a rotten state replete with corrupt courts and venal bishops. Rather than foster Anglo-American relations or portray a Romanticised ‘Old England’ as in Longfellow’s ‘The Courtship of Miles Standish’ , O’Reilly’s poem is used as a vehicle to criticize British power from a revolutionary Irish perspective. Indeed, it is the Pilgrim’s escape from the excesses of British tyranny that ironically help found America as a home for freedom. Moreover, the significance of England to the narrative is diminished due to an unusual level of emphasis placed upon the separatists’ habitation in Holland:

Then twelve slow years in Holland—changing years—

Strange ways of life—strange voices in their ears;

The growing children learning foreign speech;

And growing, too, within the heart of each

A thought of further exile—of a home

In some far land—a home for life and death

By their hands built, in equity and faith.[10]

It’s possible that O’Reilly placed intentional emphasis on the Dutch element of the Mayflower story to repudiate the growing Anglo-American dimension within Mayflower literature towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Figure 2: National Monument to the Forefathers, Plymouth, Massachusetts. Public Domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monument_to_the_Forefathers_1.jpg

The poem also make considerable use of the popular ‘Norman Yoke’ theory – the idea that an oppressive system of government was imported to Britain with the Norman conquest of 1066 – prior to which ‘the Anglo-Saxon inhabitants of […] [England] lived as free and equal citizens, governing themselves through representative institutions’.[11] The Norman Yoke myth was a popular radical expression of Enlightenment ‘natural right’ theory – arguing that the Normans had taken away an innate ancient liberty that needed to be reclaimed. An important component of British radicalism since the seventeenth-century, the idea also had purchase in Ireland (albeit to a lesser degree) where the Norman invasion was seen as the beginning of an 800 year history of British dominion.[12] In the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ O’Reilly make explicit use of this radical historical myth:

Here, on this rock, and on this sterile soil,

Began the kingdom not of kings, but men:

Began the making of the world again.

Here centuries sank, and from the hither brink

A new world reached and raised an old-world link,

When English hands, by wider vision taught,

Threw down the feudal bars the Normans brought,

And here revived, in spite of sword and stake,

Their ancient freedom of the Wapentake!

[…]

At last, the Conquest! Now they know the word:

The Saxon tenant and the Norman lord!

No longer Merrie England: now it meant

The payers and the takers of the rent;

And rent exacted not from lands alone—

All rights and hopes must centre in the throne:

Law-tithes for prayer—their souls were not their own![13]

The use of the term ‘Wapentake’ is significant, referring to an Anglo-Saxon administrative division of English countries, which were seen as proto-democracies by radicals invested in the Norman Yoke myth. Via his use of this term, O’Reilly is combining aspects of English as well as Irish radicalism and injecting them the Mayflower mythos. Norman Yoke theory played an important part in the Chartist’s struggle for enfranchisement; William Hick’s poem ‘The Presentation of the National Petition’ (1841) made direct reference to the concept:

Oh, where is the justice of old?

The spirit of Alfred the Great?

Ere the throne was debas’d by corruption and gold,

When the people were one with the state?

‘Tis gone with our freedom to vote […] [14]

By echoing well-known Chartist and Irish radical vocabulary O’Reilly is conducting an ambitious synthesis of different radical traditions. Rather than a simple celebratory ode befitting a memorial address, O’Reilly’s poem is a combative and controversial celebration of separatism and revolution. This positions the poem as a unique ideological variant at odds with much Mayflower fiction towards the close of the nineteenth century.

Additionally, O’Reilly is not content to position America as the fulfillment of liberty lacking in Britain, and instead suggests the struggle is not yet complete:

Though tongue of man hath told not such a story,—

Surpassing Plato’s dream, More’s phantasy,—still we

Have no new principles to keep us free.

As Nature works with changeless grain on grain,

The truths the Fathers taught we need again.

Depart from this, though we may crowd our shelves,

With codes and precepts for each lapse and flaw,

And patch our moral leaks with statute law,

We cannot be protected from ourselves!

Still must we keep in every stroke and vote

The law of conscience that the Pilgrims wrote.

[…]

The death of nations in their work began;

They sowed the seed of federated Man.

Dead nations were but robber-holds; and we

The first battalion of Humanity!

All living nations, while our eagles shine,

One after one, shall swing into our line;

Our freeborn heritage shall be the guide

And bloodless order of their regicide;

The sea shall join, not limit; mountains stand

Dividing farm from farm, not land from land.

O People’s Voice! when farthest thrones shall hear;

When teachers own; when thoughtful rabbis know;

When artist minds in world-wide symbol show;

When serfs and soldiers their mute faces raise;

When priests on grand cathedral altars praise;

When pride and arrogance shall disappear,

The Pilgrims’ Vision is accomplished here![15]

The final stanzas of the poem warn that although living as free people ‘[we] cannot be protected from ourselves’ and that liberty cannot be guaranteed by ‘codes and precepts’ alone. Instead O’Reilly envisions a continuous global revolution, one that will encompass ‘The death of nations’ which ‘were but robber-holds’ and the universal extension of ‘freeborn heritage’. O’Reilly’s ultimate vision is a world without borders, where ‘The sea shall join, not limit; mountains stand / Dividing farm from farm, not land from land’. Developing his rhetoric into a form of anti-nationalism, America is positioned as the beginning, not the end, of a new world based on liberty.

O’Reilly died in 1890, less than a year after the first recital of his poem. Obituaries heavily referenced his contribution to the Mayflower memorial. The Glasgow Herald made the following comments:

As showing how completely O’Reilly had won the hearts of the people, I may mention that last December, by the invitation of the Pilgrim Society, he read a vigorous poem at Plymouth, on the sport where the Pilgrims landed. That an Irishman and a Catholic should be the chosen bard of the descendants of the Pilgrims at their almost sacred anniversary would have been enough (one would think) to make Governor Bradford and Miles Standish turn in their graves.[16]

Continuing in guarded language (given his anti-British revolutionary connections) the Glasgow Herald praised his poetry as ‘expressed with energy, and without restraint’ whist suggesting that ‘the narrow limits of his early education [and] participation in Fenian plots […] stood in the way of his development as a poet’.[17]

Irish newspapers were less guarded in their praise. The Flag of Ireland noted the memorial address as evidence of O’Reilly’s ‘poetical genius’ and standing in the United States:

[T]here could not be a more remarkable testimony of the appreciation and sympathy with which his poetical genius was regarded than the fact that last year he was he poet of all America, chosen to fulfil what would be the duty of an American Laureate – namely, to compose the commemorative ode for the ter-centenary of the landing of the pilgrim fathers in New England. He was thus acing as interpreter and uniter between races that even in the New World, had been living in misunderstanding and antagonism […] [18]

The Drogheda Argus and Leinster Journal recalled his poem in glowing terms:

In the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ O’Reilly stood on the highest plane. At Plymouth that day his lines were the philosophy of history. Strong in truth they will live ever to confuse and confront religious intolerance. [19]

American accounts of his life and poetry also noted the controversy of his selection for the memorial of the Pilgrim Fathers. A 1904 edited collection of his work gave the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ poem the following summary:

In May, 1889, O’Reilly accepted an invitation to prepare a poem for the dedication of the national monument to the Pilgrim Fathers. The selection of a foreign-born citizen for this office surprised and offended many New Englanders. But all, even the most doubtful, were moved to admiration and praise when they heard the heroic strains which displayed the skill of the poet and the perfect sympathy of the writer with his subject. It was on this occasion that the people named him the poet laureate of New England… “Strange as it may seem,” writes Thomas Swift, in the Champlain Educator for June, 1904, “the ‘Pilgrims’ and Boyle O’Reilly’s inspiration were essentially kindred spirits. There is a close analogy between their lots in life, hence it is not to be wondered at that Boyle O’Reilly sang a loftier strain about the Pilgrim Fathers than any other American poet, perhaps, has done.”[20]

O’Reilly’s 1889 poem demonstrates the ability of the Mayflower mythos to incorporate disparate and sometimes contradictory narratives and ideology. From the conservative nationalism of Hemans, to the abolitionism of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, to the Irish republicanism of O’Reilly, the myth of the Pilgrim Fathers serves as a receptacle for some of the most significant political developments of the nineteenth century.

[1] T. W. Moody, ‘The Feninan Movement in Irish History,’ in The Fenian Movement, T. W. Moody, ed., (Cork: Mercier Press, 1967), pp.102-111.

[2] The Philadelphia Times, June 25, 1881, quoted in James Jeffrey Roche, Life of John Boyle O’Reilly (New York: Cassell Publishing Company, 1891), p.81.

[3] Roche, Life of John Boyle O’Reilly, p.100.

[4] Obituary: John Boyle O’Reilly, Harper’s Weekly, no. 34 (August 1890), p.664.

[5] Roche, Life of John Boyle O’Reilly, p.335-336.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Selections from the Writings of John Boyle O’Reilly and Reverend Abram J. Ryan (Chicago: Ainsworth & Company, 1904), p.19.

[8] John Boyle O’Reilly, Selections from the Writings of John Boyle O’Reilly and Reverend Abram J. Ryan, p.21.

[9] O’Reilly, p.22.

[10] O’Reilly, p.22.

[11] Christopher Hill, Puritanism and Revolution: Studies in Interpretation of the English Revolution of the 17th Century (London: Penguin, 1958), p.119.

[12] Clare O’Halloran, ‘Golden Ages and Barbarous Nations: Antiquarian Debate on the Celtic Past in Ireland and Scotland in the Eighteenth Century’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Cambridge University, 1991), pp.119-20.

[13] O’Reilly, p.22.

[14] William Hick, ‘The Presentation of the National Petition’, The Northern Star, 5 June 1841.

[15] O’Reilly, p.27.

[16] The Glasgow Herald, Wednesday 13 August, 1890, p.9.

[17] Ibid.

[18]Flag of Ireland, Saturday 16 August, 1890, p.5.

[19] Drogheda Argus and Leinster Journal, Saturday 13 June, 1896, p.6

[20] Selections from the Writings of John Boyle O’Reilly and Reverend Abram J. Ryan (Chicago: Ainsworth & Company, 1904), p.19.