Deep in the countryside of Buckinghamshire, in the small Quaker village of Jordans, lies an old wooden barn. Quaint, if unremarkable, it probably dates to the early part of the seventeenth century. Today, it is part of a private multi-million pound estate – still visible from the road, but shut off from the public. Rewind a hundred years, and scores of people came flocking from around the country (and even the United States) to catch a glimpse of the interior. Articles about the barn were featured in local newspapers and many of the nationals too. Amazed or dubious, journalists reported the most incredible of happenings: an Englishman, James Rendel Harris, had found the last resting place of the Mayflower.

The Mayflower Barn – old postcard in possession of author

Harris, a biblical scholar in his late 60s, believed that timbers from the old ship had been used to construct the barn. He breezily told the press that he had been attending a funeral in the area when a man told him this fact – though he was now ‘unable to trace’ this mysterious local expert. He was compelled to investigate the farmstead. According to his research, two local farmers, who had shares in the Mayflower in the 17th century, may have received its timbers after it was broken up. Harris put this information together with details gleamed from the history written by the Plymouth Colony’s first governor, William Bradford. According to this most venerated of Pilgrim Fathers, a large beam on the ship had cracked; low and behold, one of the Barn’s timber’s had been repaired with a fishplate. Harris also brought in experts to examine both the brickwork (who found it supposedly dated to the period) and the timbers (shown to belong to a vessel similar to the Mayflower’s size). More speculative were the deductions he made from carved inscriptions on the timber – the letters ‘HAR’, he argued (and if you squint), maybe referring to Harwich (the ships port of registration)

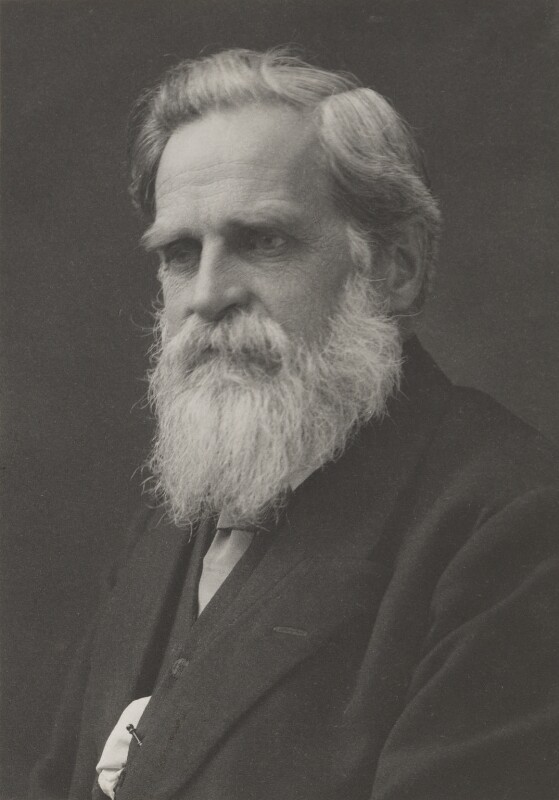

James Rendel Harris by Walter Stoneman (1916), NPG Ax39095, © National Portrait Gallery

If the story seems dubious, the circumstances of Harris’s life might make us even more suspicious. He was a veteran member of the Quakers, and had ceremonially opened a Quaker Hostel in the village just a few years – which itself had only recently been re-founded as a Quaker settlement. He was also a leading figure in the English Mayflower Club, and an author of Mayflower plays. So Harris had a motive – ‘providentially happy’ as one newspaper put it – to unexpectedly find the Mayflower in Jordans. Not only did the discovery boost the wider interest in the Mayflower as the 300th anniversary in 1920 drew nearer, but it also gave an air of historical legitimacy and importance to the fledgling Quaker community.

The public – both in Britain and the USA – went wild for this ‘Mayflower Barn’. Audiences came from far and wide to hear Harris lecture underneath its old beams, where he told them ‘the spirits of the departed Pilgrim Fathers may be looking over your shoulders.’ A charge was introduced for those hoping to get inside, and some even tried to chip off bits of wood to take home as souvenirs. Not everyone was convinced by Harris’s story, though. J.W. Horrocks for example, a professor of history at University College Southampton, wrote into the Times Literary and attempted to destroy the historical basis for Harris’s claims. The eccentric Harris was undeterred – he instead celebrated the importance of ‘folk memory’ and ‘local tradition’, rather than a stricter interpretation of historical fact, and continued to push the story throughout the 1920s in speeches and popular books.

More interesting even than the idea that the Barn could actually be the Mayflower, was how it became a vibrant site of historical culture in itself. In 1921, in the shadow of the First World War, the Quakers presented a part of one of the timbers to Samuel Hills (an American Quaker), who placed it in a chest inside the Pacific Highway Association Peace Portal (today Arch) on the boundary of the USA and Canada to commemorate the ‘common ancestry’ and century of peace between the US and Great Britain. At a strange ceremony in the barn, national representatives took turns using a saw to remove the wood before Hills said, ‘with great emotion’, ‘I thank thee, and I take it feeling the responsibility it conveys – a link of peace between Great Britain and the USA.’ In following years American interest in Jordans continued to blossom – from offering to erect a ‘costly mausoleum’ over the nearby grave of William Penn (rejected by the local Quakers who, like the Buckinghamshire Examiner, were probably ‘aghast’ at the ostentatious proposal), and even attempting to transport the Barn to be reconstructed in America (again rejected after ‘widespread antagonism to the proposal’). During the Second World War, wood from the rafters was even used to create a ‘Mayflower medal’ for Winston Churchill to give to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

‘Peace arch Canada-US border’ taken by Abhinaba Basu (2012). CC Commons: https://www.flickr.com/photos/abhinaba/6879528558

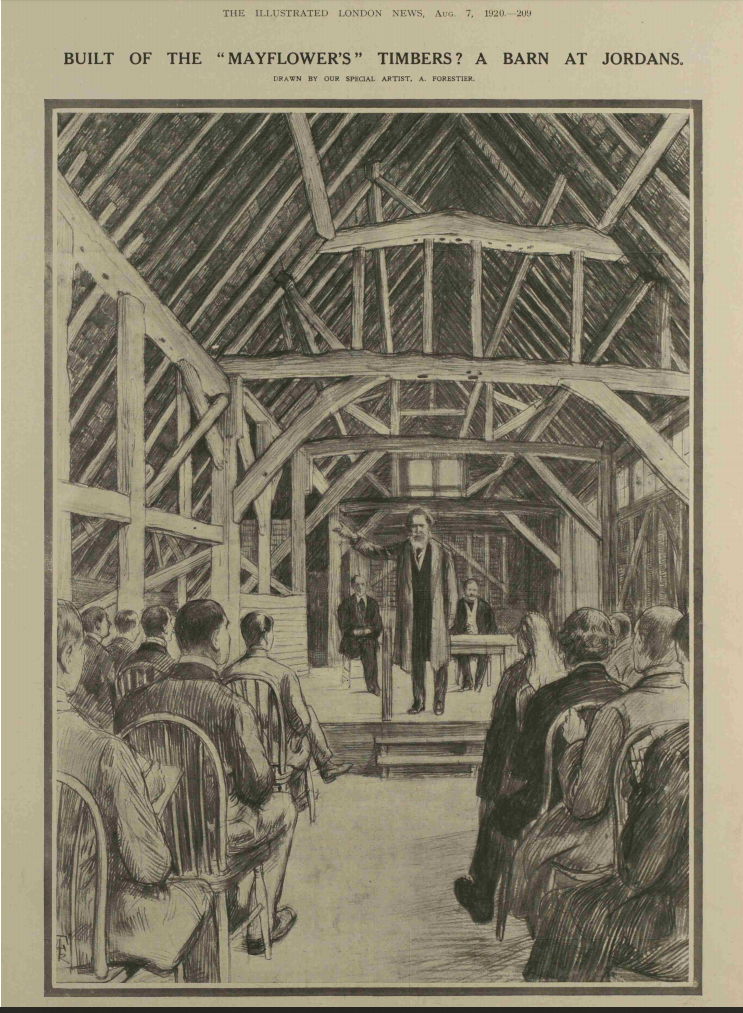

Long after its ‘discovery’, the Mayflower Barn continued to shape popular understandings of local and national history. Artists, like Amédée Forestier, visited to sketch this curiosity, while local groups put on musical concerts and performances. The Barn came to represent a sense of ‘Englishness’ – one that thrived on romantic evocations of rural historicity. When the Amersham Rural District Council foolishly proposed to construct a main by-pass road in 1928 that would pass through Jordans valley and near both the Barn and the historic Quaker meeting-house, the strength of the local outcry forced them to reconsider. As an editorial in the Manchester Guardian gushed, ‘All those who love rural England and believe that there are memorials of the past worth preserving and a heritage of beauty which is valuable’ would be ‘grateful’ to those that were mobilising (including such powerful figures as former Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, who signed a letter of opposition). Ernest Warner, clerk of the local Society of Friends, summarised the feeling well: ‘this place should be preserved as a heritage from the past and an inspiration for the future.’

Illustrated London News (7 August 1920), © Illustrated London News Group

By the 1940s or 1950s a lot of the interest in the barn and the fiercest debates about its authenticity were beginning to die down. There was some minor coverage around other notable events of Mayflower enthusiasm, such as the sailing of a replica in 1957 or when a small play about the voyage was held in the barn in 1969. But the focus on the Pilgrim Fathers had receded in the local imagination in favour of a more general (and casual) enthusiasm for its symbolic pastoral ‘Englishness’. By the early 1960s, the structure was in need of substantial work, and the local Trustees of Old Jordans were struggling to find the money. Thankfully, the Pilgrim Trust eventually (after some wrangling) contributed a much-needed £1,000 – though they declined to endorse the authenticity of the Barn, as did the Inspector of Ancient Monuments on behalf of the Historic Buildings Council for England. When the Barn was Grade II listed in 1982, it was primarily on the basis of its 17th century origins – though the listing did mention how it was ‘Noted for Quaker Associations and held by some to incorporate timbers from the Mayflower in which the Pilgrim Fathers sailed in New England in 1620.’

© Copyright David Squire and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

© Copyright David Squire and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Interest continued to recede in the 1980s and 1990s, with little rumination on its symbolic importance as either a vector of historic Englishness or a symbol of Anglo-American friendship. In 2006, the barn was sold off into private ownership, its general historicity used as a Unique Selling Point – but now for one wealthy individual rather than the nation at large. Miffed TripAdvisor reviews from visiting Americans, who can now not access the famous ‘Mayflower Barn’, are testament to the interest that the site still holds to some. But the days of Harris’s explosive discovery – and the intense historical scrutiny and celebration that brought – are over.

Final Jeopardy answer tonight was The Mayflower. This evoked memories as a child going on a school visit to Jordan’s to see the Mayflower Barn and learn about the Quakers, Pilgrim Fathers and William Penn (local school named after him). Living in Canada since the age of 20, I treasure these memories. Now if my short term memory was minutely similar I would be thrilled

The book I wrote called The Mayflower of Harwich, which is being sold on Amazon on e-book format at a ridiculously low price, will confirm that the Mayflower Barn at Jordan’s Buckinghamshire does contain the timbers of the the Mayflower that took the separatists, later penned as The Pilgrim Fathers.

I visited the barn and spoke to the Quakers there and also saw the third replica of the ship made from some of the unused Timbers. The other two were presented to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill in WW2.

Please read my book as there is much more information about the Mayflower than what is in any of the pre Internet books

Paul Simmons

Harwich, UK

My great grandfather was the construction manager for Samuel Hill and was a supervisor of the building of the Peace Arch. A little known fact is that when the piece from the barn was brought over for insertion into the arch, they had measured incorrectly and it was too big. The leftover was in two pieces: one is in the Samuel Hill Museum (called Maryhill) in Washington State. The other piece was given by Samuel Hill to my great grandfather and our family still has it, in safekeeping. We have no information as to whether the barn is really the Mayflower, but that was the thinking at the time.

Also, it just so happens that our family is a (for whatever it’s worth) Mayflower descendant family. The genealogy has been certified and we are direct descendants of John Howland (the midshipman who fell overboard in Plymouth Harbor and was hauled back to the ship) It is a direct line from John Howland through the centuries along the Bassett line My maternal grandmother’s maiden name was Bassett.

Although it doesn’t necessarily mean all that much in the big picture, it’s always nice to know where you came from.

Thank you for sharing that wonderful information, David!

I am a direct descendant of Thomas Goffe who owned part of the Mayflower but who waited quite some before sailing to America with his wife an unborn child. He died shortly after arriving.

I think this is cool as heck. The info is neat. the mayflower is still around after all these years would love to see it n person someday

I wish there could be a dendrochronological study of the wood in the beams of the barn.. Maybe some carbon dating could be done as well..

It’s a sad state that no one can see the barn in person anymore.. I guess that’s the new state of progress..