*Guest post by Adrian Gray, historical adviser to Bassetlaw Christian Heritage and director of Pilgrims & Prophets Christian Heritage Tours*

Growing up in Lincolnshire and now living just on the Nottinghamshire side of the border, I’ve long been aware of the ‘Mayflower’ story but have also noticed that its local impact has been small. In the Scrooby/Gainsborough area there has never been any statue and all the memorial plaques were, until recently, mainly the work of American Congregationalists. On the coast, 45 miles away, are two memorials also funded by Congregationalists and neither in the correct place. ‘Locals’ seem to have seen it as a story about someone else.

With Mayflower 400, there was some growing local interest – partly because many of us have been active in re-shaping the story so that it has clear local relevance. The focus on William Brewster and William Bradford, people who were not that important while they were here, has been at the expense of understanding local context; nor has there been much awareness of what happened here after ‘they’ left.

Memorial to the Pilgrim Fathers, erected at Fishtoft, Lincolnshire, in 1957 – photo reproduced by permission of Heather Wilkinson Rojo

Before

Brewster, Bradford and John Robinson were minor players in Notts/Lincs puritanism before 1606 – so to focus just on them is to miss the story. More helpful is to trace the development of local radical evangelical activity, which we can start from the ‘nest’ of radicals in Boston in the 1520s documented in MacCulloch’s book on Thomas Cromwell. Two of these radicals (Thomas Garrett and Robert Testwood) ended up being burnt for heresy (three if you include William Tyndale, who visited briefly, and for other reasons Cromwell himself, who knew them all).

Boston can easily be linked to Thomas Cranmer, born in Nottinghamshire with Boston connections, who maintained close links with the two counties throughout his life. One of those links was Sir John Markham, an early evangelical whose dense network of local relationships around Newark included the family of Sir John Hercy of Grove – the dominant evangelical figure in north Notts in the 1530s and 1540s. Hercy’s relatives included John Lassells of Sturton, burnt in 1546 for denying the ‘real presence’ in the communion bread and wine. That’s the same Sturton that produced John Smyth and John Robinson. Anne Ayscough (or ‘Askew’) of Lincolnshire died with him.

It is easy to get from Hercy to the ‘Mayflower’. Hercy left his Retford lands to William Denman; the Denmans prospered and included Nottingham radical Walter Travers in their numbers whilst Richard Clifton, the famous Babworth minister, inherited books from one of them. We see the same clergy serving in Scrooby and also the Denmans’ church at West Retford. Other local gentry families were also enthusiastic promoters of religious radicalism – the Wasteneys a good example.

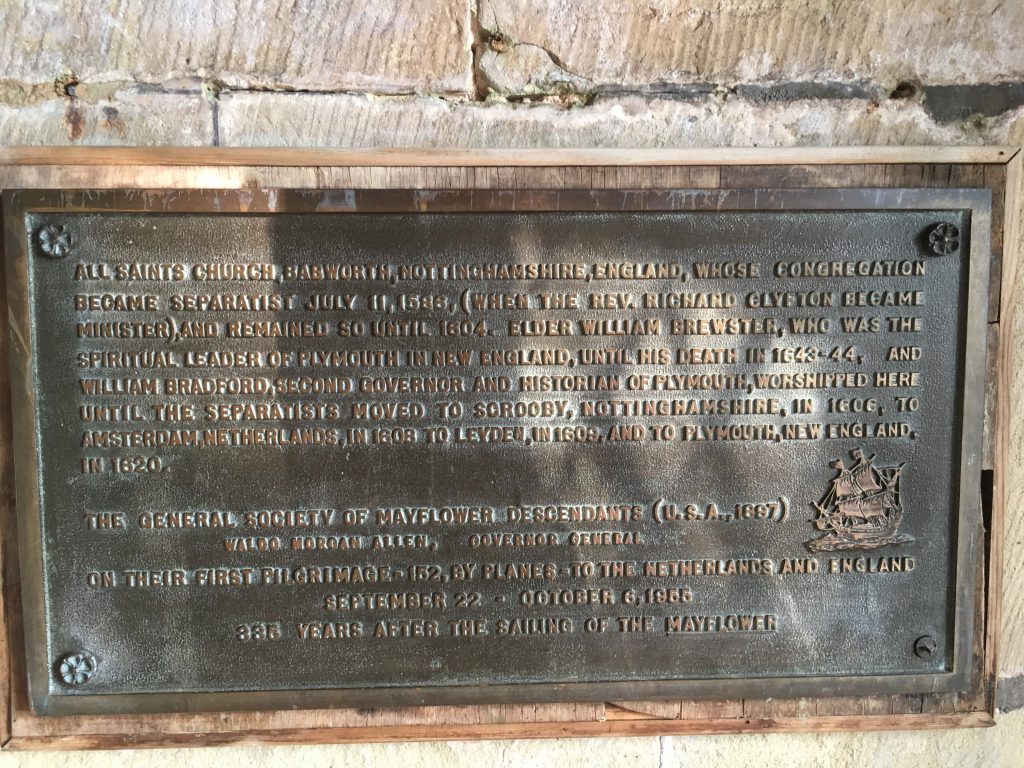

A bronze plaque donated by the General Society of Mayflower Descendants in 1955 and unveiled in All Saints, Babworth. Picture by author.

In Lincolnshire, the Duchess of Suffolk promoted a network of religious radicals soon emulated by lesser Lincolnshire gentry in families who had served her first husband or shared her opinions. One example is the Wray family, children of a Lord Chief Justice on one side and Suffolk clients on the other, who were dominant around Gainsborough and promoted the emerging ‘senior’ leaders among the local radical clergy – Richard Bernard in Worksop and John Smyth, who eventually formed the Gainsborough congregation. The Wray maternal side included the first clergyman to be deprived for nonconformity in Elizabethan England. It was in a Wray house that the key debate about separation took place; Brewster and Bradford were not there. Meanwhile a group of the Retford radicals, led by the Denmans, were arrested for illegally attending a sermon by Robinson at Sturton.

Clearly these people made use of established connections in Boston when trying to leave the country. In the end it was Thomas Helwys, who was at that key meeting, who organised the final departure from Gainsborough.

After

However many went to Holland, it was clear that most of the local radical puritans did not. They stayed to fight it out with the Church of England; clergy like Brian Barton in South Collingham did so for decades with a good degree of success, while Thomas Hancock always had a friend to find him a good place. During the relative calm of the 1610s and 1620s, such men might have wondered why Robinson and others had gone to the Netherlands at all. Meanwhile local gentry continued their policies – Isabel Wray for example planting the radical Ireton family into Attenborough with inevitably turbulent results.

Statue of Isabel Wray, part of the Memorial to Sir Christopher Wray in St Michael’s church, Glentworth

Meanwhile the seeds sown by the Duchess of Suffolk (an evident supporter of separatists in 1560s London), who had died in 1580, began to produce a harvest with help from associated Lincolnshire gentry and their radical preachers. The first of these harvests, the ‘Great Migration’ of 1629-34, was heavily dominated by people from Boston and the neighbouring heartlands of the Duchess’s old territory; the famous Anne Hutchinson of Alford was a descendant of a family that had served the Duchess’s husband in the early 1530s. But we could go back earlier – Captain John Smith himself came from the same clientele.

The second harvest was the opposition to the policies of Charles I and William Laud which gathered pace during the 1630s. The men who led this were from the Suffolk-legacy county gentry: Edward Ayscough, Sir Thomas Grantham, Sir Christopher and Sir John Wrays plus Sir Anthony Irby and Sir William Armyne from the same area. All had been part of the puritan vanguard for two or more generations. Several went to prison for refusing to pay the King’s new taxes. In Nottinghamshire, opposition was led by the Hutchinsons and their friends the Iretons, clients of the Wrays, part of the same radical puritan group. Edward Whalley was of the same family that had given Richard Bernard the job at Worksop in 1601. We all know how this ended.

By putting the ‘Mayflower’ back into the context of the region from which the enduring New England leaders came, we thus get a different perspective. The ‘trip to Amsterdam’ in 1608 was just one episode of a radical story stretching from Boston in the 1520s until it came to a juddering stop in 1660. Along the way, it also produced the Quakers.

And it produced something else. The ‘Mayflower’ may be of importance to specific Americans, but the Gainsborough separatist congregation produced a greater gift for everyone. In the Netherlands they embraced the ideas of believers’ baptism and religious liberty for all people. Smyth, Helwys, John Murton and John Spittlehouse were all Baptists with Gainsborough links who produced a coherent argument – the first in English – for the separation of all religion from state control. They can claim influence on the US First Amendment and the UN Declaration of Human Rights; and that is a legacy for everybody.

Adrian Gray is the author of Restless Souls Pilgrim Roots: the Turbulent History of Christianity in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, published by Bookworm of Retford in 2020.

If you would like to write a guest post for our blog, you can get in touch with us at t.hulme@qub.ac.uk

Excellent article I enjoyed reading this. We have such a rich tapestry of history all around our area of Retford and Gainsborough. Looking forward to the next instalment, perhaps the Denman’s?