*Guest post by Randal Charlton, author of The Wicked Pilgrim*

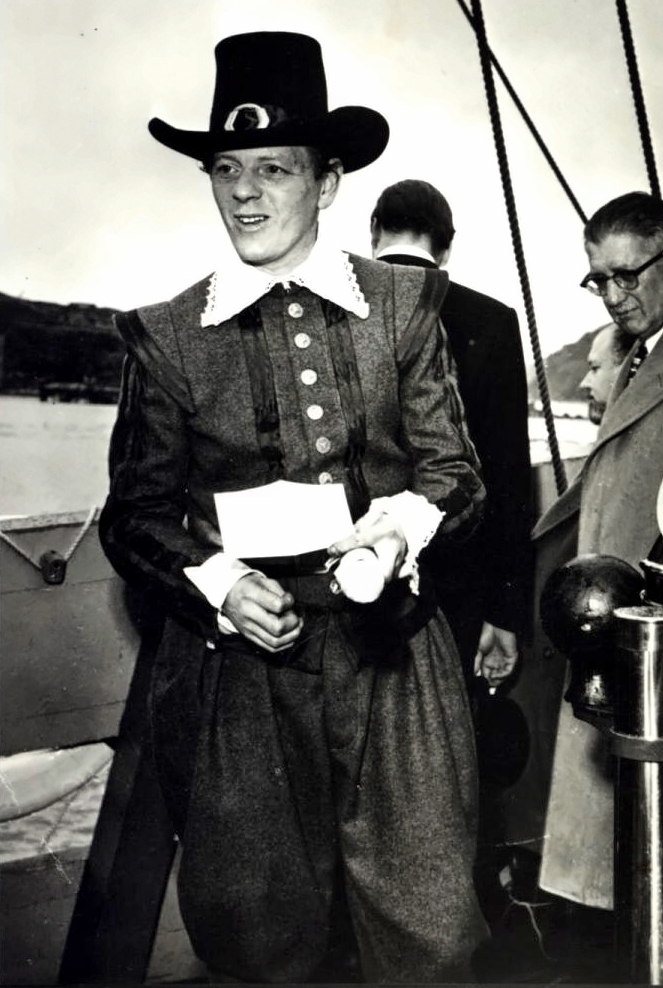

Chris Devers, Mayflower II (2008) – Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Both the Statue of Liberty and Mayflower II were given to the American people – but there the similarity ends. The Statue of Liberty was a gift to America for offering a new home to everyone seeking a new life and new opportunities. It was a gift of the French government. It was one nation to another. On the other hand, the gift of Mayflower II has been shrouded in mystery and misinformation in the sixty plus years since it was given to America. Some have assumed that the ship they see today was the original; others that it was a gift of the British government, and some have heard that the English people gave Mayflower II to America.

None of these assumptions are correct. The original Mayflower was broken up a year or so after it returned in England in 1621. There was more than one plan for the replica that was built in 1957 but politics intervened and my father, Warwick Charlton, who conceived the idea of building a replica of the Mayflower, ended up taking full responsibility for completing the entire project. In the process he suffered lasting damage to his financial wellbeing, his career and his reputation which took many years to repair.

So, who was this man who in September 1957 put his sole signature to a document transferring Mayflower II to American care for the nominal sum of one dollar?

If I had to sum up my father in a sentence or two I would say he was a shy man but a man with great passions, one of which was a love of history; a man possessed of immense, sometimes manic energy and certainly not someone who would be ignored when he walked into a crowded room. He was built as tough as teak; over 6ft tall with a powerful voice that he used to good effect when arguing for the causes he believed in.

Warwick Charlton was thirty-five at the time that he decided abandon his career as a writer to pursue his Mayflower dream. He had enjoyed success as a playwright, author, a broadcaster, a reporter and a very successful newspaper editor. These talents were recognized by no less than Time magazine who praised his amazing ability to produce papers under the most extreme war time conditions. Time magazine also noted his tendency to challenge authority. If he sounds like a rather exotic character, well, he came from exotic parents.

His 6ft 5in tall father was a newspaper drama critic, a friend of royalty, politicians, newspaper editors and stars of the theatre, who dressed for work in full morning clothes including waistcoat and top hat and was known as the Last of the Dandies. His mother, the daughter of East European immigrants, was a talented student who chose acting over academia and enjoyed a career as a noted performer on the London stage.

My father had a middle-class education at a school where students were encouraged to pursue a career in medicine. He developed instead his passion for history. He had no lessons in business. He also had no knowledge of ship building and sailing and had never been to the United States.

So why on earth did abandon his career in 1954 to follow his Mayflower odyssey?

There were two reasons, I believe; one related to Great Britain, the other to America. The United Kingdom of the 1950s had emerged from the second world war with its cities and infrastructure in ruins. At the same time, it had lost an empire that encompassed one third of the world – including Canada, India, Australia and New Zealand. All that was left for postwar Britons was just the boring brick by brick business of rebuilding bombed out British cities. “Where was the sense of adventure?” Warwick wondered. “Where was the food for our spirit?”

Of equal importance, ever since the end of the second world war, Warwick had been nurturing the idea of a gesture to America that would thank the United States for their leadership role in preserving freedom and democracy in two world wars and the first half of the twentieth century.

As it happened Warwick had a front row view of American generosity in World War II. The British eighth army in which he served on General Montgomery’s staff was being pushed back across north Africa by troops commanded by Germany’s Field Marshall Rommel. Britain was fighting a losing battle in large part because they had inferior equipment, in particular tanks that kept breaking down in the extreme desert conditions.

Warwick was convinced that the war would have gone in a very different direction if America had not supported the allies at this critical time in the conflict.

Warwick was designated to greet emissaries sent by President Roosevelt including former New York Governor Wendell Willke. In short order much better American built tanks and equipment arrived and the tide of the battle turned. British troops that had been retreating desperately, now with American tanks advanced relentlessly across north Africa, into Italy and on to victory. Warwick also noted the courage of American troops beginning with three squadrons of elite volunteer airman who entered the war early on. On a broader scale there were the American liberty ships, the lend lease program. Postwar the US Marshall plan helped European allies rebuild.

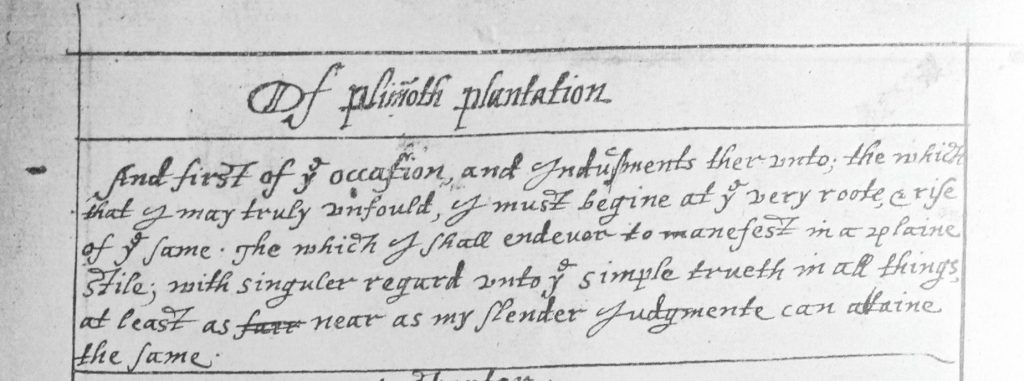

My father, an avid reader, happened to pick up a copy of William Bradford’s seventeenth-century history of Plymouth Colony on his way home from the war on a troop ship in 1947 and was struck by the courage of the early settlers. And for several years postwar he toyed with the idea of thanking the American people for their modern-day courage and leadership in protecting democracy and freedom around the world by giving them a piece of their history – a replica of the original Mayflower.

In the beginning he did not think he would do it himself. He would persuade his wealthy employers, media barons like Lord Beaverbrook or Sir Edward Hulton, to put up the money. He approached the English-Speaking Union and numerous other reasonably well-endowed organizations and individuals but one by one they turned him down.

At one point he was standing at the bar of the Red Lion pub just off London’s famous Fleet Street bemoaning his inability to interest people in his Mayflower idea when a colleague turned to him and said, “Let’s face it Warwick Mayflower II is never going to happen.” Warwick apparently slammed his beer mug down on the bar counter and announced in a booming voice to anyone within earshot that he would not drink another drop of beer until Mayflower was built and sailed across the Ocean to America.

That convinced at least the assembled journalists and printers in the pub that Mayflower II really was going to happen and happen it did. In just over two years, my father found plans for the ship where none existed, a builder for the lost art of wooden sailing ship construction, a captain and crew to sail it across the Atlantic and American partners to look after it after arrival. Above all he found the money to carry out the project, which in today’s money would be millions of dollars.