The nineteenth century witnessed a proliferation of literature written for children which sought to both entertain and offer moral instruction for the young. A revolution in cheap printing and childhood literacy rates meant that suddenly new readerships were forming. As Ruth Jenkins comments:

The Victorian convergence of advancing technologies, greater leisure time for emerging middles classes, and increasing literacy rates propelled narratives written for children into a recognisable genre and a bourgeoning industry. Heralded as a ‘golden age’ of children’s literature, this period invites continued study of these texts as cultural responses that give insight not only in what concerned Victorians but why they remain viable narratives today.[1]

This was coupled with a growing concern over childhood, child welfare, and children’s education. The result was literature produced for children like never before, and the story of the Mayflower played a central role.

The Victorians had a fascination for the Mayflower story. Felicia Hemans’ well-known 1825 poem had helped create a market for songs, plays, novels, and poetry that featured the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ as they founded a New England colony in dire conditions in the winter of 1620. Many of these Mayflower products were aimed at children and adolescents; a great volume of children’s novels, poems, and illustrated gift books were produced that retold the story of the Pilgrims. These were popular texts that were sold throughout the nineteenth century (and indeed, into the present day). In this feature, we take a look at some examples published in Britain from the 1850s to the 1890s.

Many Mayflower novels for young readers had moral or religious themes, teaching the importance of hard-work, self-sacrifice, and faith in God. An early example of this was Anne Webb’s The Pilgrims of New England: A Tale of the Early American Settlers (1853). The preface to The Pilgrims of New England provides a detailed breakdown of Webb’s intension for the novel, which was to ‘illustrate the manners and habits of the earliest Puritan settlers in New England and the trials and difficulties to which they were subjected during the first years of their residence in their adopted country’.[2]

The novel begins with an extract from the opening lines of Felicia Hemans ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ (1825). The first paragraph builds directly upon Hemans’ work, extending the high-drama and Romantic sensibilities of the poem into exciting prose:

It was, indeed, a ‘stern and rock-bound coast ‘ beneath which the gallant little Mayflower furled her tattered sails, and dropped her anchor, on the evening of the eleventh of November, in the year 1620. The shores of New England had been, for several days, dimly descried by her passengers, through the gloomy mists that hung over the dreary and uncultivated tract of land towards which their prow was turned; but the heavy sea that dashed against the rocks, the ignorance of the captain and his crew with regard to the nature of the coast, and the crazy state of the deeply-laden vessel, had hitherto prevented their making the land.[3]

The hardships of the tumultuous landing are dramatically illustrated in the novel’s frontispiece. Ultimately, these hardships are overcome through community, faith, and perseverance. Webb reminds us that in the end the ‘English Puritans have taken root in the American soil, and flourished so greatly, that a few years ago their descendants were found to amount to 4,000,000.[4] In short, such Christian virtues helped build the American nation.

Webb’s novel is also indicative of the importance of female authors in the popularisation of the Mayflower narrative in British fiction. Indeed, female authors, illustrators, and poets were instrumental in popularising the myth of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ for British children. For example, Three Gems in One Setting (1860) lavishly illustrated by Anne Lydia Bond (1822-81), an artist and photographic colourist, provides artwork to accompany Hemans’ ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England (alongside Tennyson’s ‘The Poets Song’, and Thomas Campbell’s ‘The Field Flowers’).[5] Three Gems in One Setting is a gift-book for children of the growing middle classes. At 15 shillings, the book was expensive, reflecting its high production costs and use of chromolithograph printing.[6] Its artistic design is highly intricate: images are presented with interlaced floral borders which imitate medieval illuminated manuscripts, a style popularised by the Pre-Raphaelites and common in mid-century Victorian art.[7] Bond’s selection of Hemans’ poem as a popular and celebrated ‘gem’ speaks to its value and status in the Victorian marketplace. Its artwork serves a moral as well as an aesthetic purpose: the images of dutiful pilgrims struggling in adversity would hopefully instil such values in its readers.

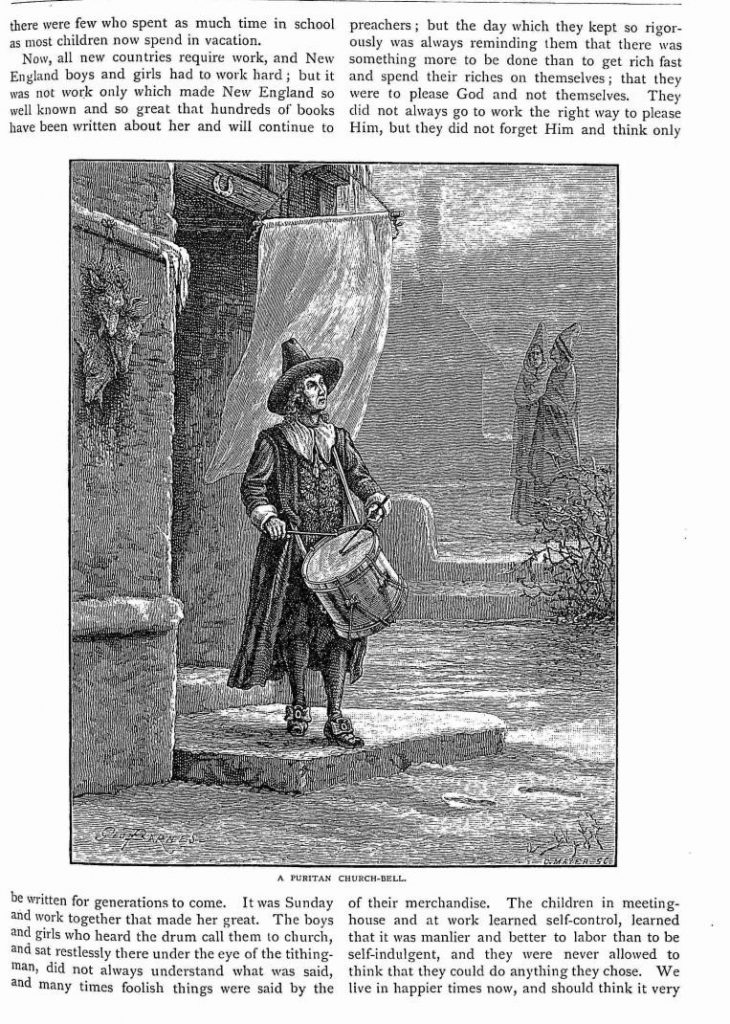

St Nicholas Magazine (1873-1940) was a Anglo-American monthly illustrated children’s magazine published in New York and London ‘For Young Folks’.[8] The work was praised by leading poetical figures of the period such as Christina Rossetti: ‘As to ‘St Nicholas’ I cannot fail to admire its attractively beautiful appearance, & to wish myself a nook in its pages’.[9] The April 1879 edition of the magazine opens with an illustrated short story ‘The Little Puritans’ by Horace Elisha Scudder (1838 – 1902). The story begins by discussing the ‘Old England customs’ brought by the ‘New England ancestors’ and provides examples of seventeenth-century life. Scudder describes the lack of church bells in the early days of the settlement: ‘they did not at first bring bells for their churches, instead, a man stood on the door-step and beat a drum’.[10] Churches are described as unadorned ‘meeting-houses’ where ‘very likely the floor is sanded’ and in winter boys would bring ‘little foot-stoves for their mothers and sisters to put under their feet during the long service’.[11] The story celebrates the religious history of New England by stressing the frugality and work-ethic of the seventeenth-century puritans. The correspondence section of the magazine ‘The Letter Box’ contains a response to a young reader asking if the children aboard the Mayflower had much time for play:

The children on board must indeed have been tired of their five months voyage, cooped up with so many stern-looking men and sad-faced women in such a little vessel […]. However, the little Puritan boys no doubt had some good times in the few sunny hours of the weary journey, for sailors were fun-loving folk even in those days of hard, solemn living.[12]

St Nicholas configures an instructive religious and moral fable from the story of the Mayflower. The humble and pious beginnings of New England are stressed as the starting point for the successes of the colony, and by extension, the United States. The subtext appears to be the dangerous growth of luxury and commercialism in the mid to late nineteenth-century.

The central Victorian ethic of self-sacrifice featured in many Mayflower works for children.[13] Ilana M. Blumberg notes how self-denial was ‘sanctioned by ancient Christian tradition and by the latest impulses of Protestant evangelicalism’.[14] Furthermore, in a society where laissez-faire capitalism was seen by many to promote individualism and self-interest, such ideals could, it was hoped, qualify those impulses and promote collective benefit.[15] In celebrating ‘days of hard, solemn living’ and contrasting them with the modern world ‘Little Puritans’ seems to be offering a similar moral message.

A late-nineteenth-century example of British Mayflower fiction is the illustrated Mayflower Pilgrims (1898) by Kate Thompson Sizer (1857-1909). Sizer frequently worked with children’s illustrator Matilda Maria Blake (b.1856). Unfortunately, there is little no to biographical information or extant scholarship on either women despite being prolific female publishers at the end of the nineteenth-century whose work was well-received in the press. This is a common problem for female authors from this period.

Like Annie Webb’s novel from half a century before, Mayflower Pilgrims opens with a stanza from Hemans’ ‘The landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’:

“What sought they thus afar? –

Bright jewels of the mime?

The wealth of the seas, the spoils of war?

They sought a faith’s pure shrine!”

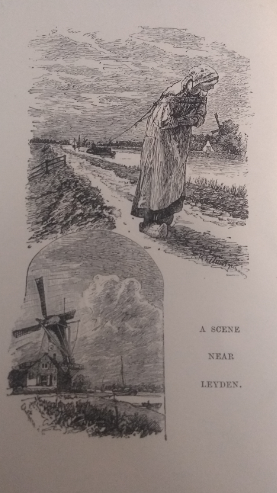

This stanza is central to Heman’s description of sacrifice made in the service of a religious mission and helps set the tone for the opening of the novel. This is also true of the opening illustration, an image of a women pulling a barrage along a canal, bent over in pain, demonstrating the lived reality of hard personal labour endured by the book’s characters.

Unlike Hemans, however, Sizer’s story focuses on twin sisters named Grace and Annis, living in Leyden shortly before the departure to North America. Providing exposition and context, Sizer recounts the children’s knowledge of their status as exiles and the reasons why they are living away from England:

The children chatted to each other in English, but they could understand perfectly the Dutch words spoken by the bargemen and the peasants. Eleven years – longer, that is, than they could remember – they had lived in Leyden. Grace and Annis were only babes, and Arthur a toddling boy, when their parents left England. James I., the king whose name is in all our Bibles, was ruling then, and though he was in some ways a good king, and wished all his people to be religious, yet he made the mistake of wanting them to be religious only in his way. Those who would not be so he punished. To escape this punishment, the children’s parents and many other good men and women, came to Holland and settled in Leyden.[16]

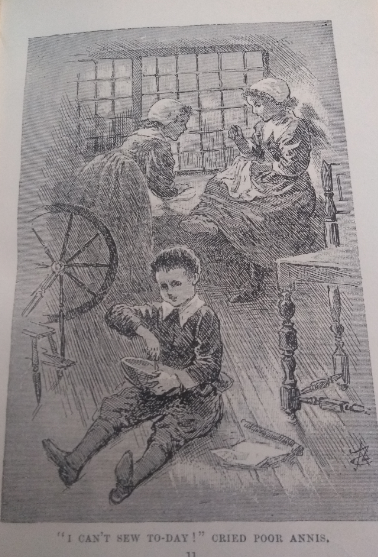

Expanding on the theme of hardship established by the opening image, the children are expected to work hard to support their families. This is highlighted in the opening pages of the text where Annis and her sister struggle to complete their needlework:

“How slow you are, Annis!” said Grace the elder twin, in her quiet voice, as she watched her sister at her task.

“There! My cotton has broken and my needle come untethered again,” answered Annis impatiently. “Grace you have not quite done yours, have you?” [17]

Child labour is also highlighted in one of the opening illustrations (pictured). This was a society that was changing the way it understood child labour after the introduction of The 1870 Education Act – the first item of parliamentary legislation to deal with the provision of childhood education in Britain. Sizer seems to place particular emphasis on the historical reality of the difficult life the separatists faced. This is compounded by their arrival in North America:

They all needed warm clothes, for bitter, bitter was the first winter after the landing of the Mayflower Pilgrims. The deep snows lay like a white blanket on the little settlement, and morning after morning they woke to find the north wind blowing, and the snowflakes driving in through wooden shutters and the crevices in the roughly-built walls. Before that terrible winter was over half of the Pilgrims lay sleeping in the little burial-ground on Cole’s Hill, victims of cold and hardship.

Such sad events made the children wise and brave before their time; and Annis, as she lay awake, was praying earnestly that God would soon make her mother well, and would bring her father back safe from his journey.[18]

The situation does not improve, and the narrative of Mayflower Pilgrims turns into one of survival against the odds. We are told how ‘disease had thinned the numbers of the Pilgrim Fathers’ and that ‘as their supplies ran short, famine came among them to claim fresh victims’.[19]

Ultimately, however, it is explained that such immediate suffering will be redeemed in the future by the success of the United States of America:

All that is best and truest in America to-day can be traced to the brave little band who, on Plymouth shores, suffered such terrible hardships.[20]

This is a crucial intervention by the text’s omniscient narrator. At this moment the narrative voice intervenes to console the reader and provide a reason for the misery that has been described in such detail. In this way, Sizer is directly contributing to the use of the Mayflower narrative as a quasi-religious foundation myth, drawing implicit parallels between with the Christian narrative of suffering and redemption and the establishment of New Plymouth, and eventually, the United States.

As the story continues Annis must travel on her own to a nearby settlement to beg for food:

Annis put on her hood and cloak, both much worn by the hard winter’s service, and set out. As she ran down the snow-covered track, which as present served Plymouth as a road, a keen north-west wind was blowing. She pulled her hood far over her face to shield herself from its icy breath, but a white line of snowflakes was on her head and shoulders when she stood before the good deacon’s door. “Can you lend us any food? Grace and I have none.” She asked eagerly, as kind Deacon Fuller appeared at the door in answer to her knock. The good man looked sorrowfully at her. “Little maid, we are in the same case ourselves. No morsel of food has passed our lips to-day. […] [21]

Her family are rescued from immediate starvation by their father hunting a deer, more significantly, however, it is the supply of Maize to plant in the spring from the local Native American tribe provides them with a secure future. This ties the story into the American Thanksgiving tradition, which had also come to be associated with New Plymouth in the nineteenth century but actually had its origin a separate New England Calvinist religious tradition.[22] Part of the success of the Mayflower mythos has been its ability to absorb other myths into its narrative over time, this includes the beginnings of American democracy, religious freedom, human-rights, and self-determination. Many British authors have helped shape this accumulation of myth-making, and Sizer is contributing to the establishment of the Thanksgiving ceremony as an intrinsic part of the New Plymouth myth in Mayflower Pilgrims.

After this critical juncture, the suffering and starvation is over, and the children enjoy are free to enjoy a hopeful future:

More emigrants came from England, and the hills and woods that were so lonely when Grace and Annis first looked at them from the deck of the Mayflower became peopled with many happy homes. When they heard from these new-comers that in England the Puritans were still persecuted, when stories reached them of Banyans’ eleven long years imprisonment, and of good men like Richard Baxter dragged in old age and sickness before harsh judges because of their religion, then they thanked God that they lived in a free land where they could serve Him as they would.

Brave Pilgrims of the Mayflower! [23]

Like many of Sizer’s works of children’s fiction, there is a clear religious message at the heart of Mayflower Pilgrims, one that demonstrates the value of suffering for faith in difficult circumstances. Moreover, the story functions almost as a national-religious parable, rooting ‘All that is best and truest in America’ in the trials and of an early band of benighted religious exiles.

There was a rich variety of Mayflower children’s literature published over the nineteenth century. The works cited above are just a snapshot of some of them. These texts were aimed at children from different age groups, social classes, and levels of education. As Bratton comments, this was a common feature of childhood literature in this period:

[C]hildren’s books were being written throughout the century which were supposed to suit their level of literacy, their stations in life, and their expectations of the future, and to reflect their present experiences so as to mould through their response to it their moral and social attitudes.[24]

Much work has been done on the development of Victorian literature, and how it attempted to instruct the ‘moral and social’ attitudes of young readers. However, the voyage of Mayflower and the story of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ has not been as seriously examined for the unique role it played teaching Victorian children about faith, morality, and British identity in a changing world.

[1] Ruth Jenkins, Victorian Children’s Literature: Experiencing Abjection, Empathy, and the Power of Love (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), pp. 2-3.

[2] Annie Webb, The Pilgrims of New England: A Tale of the Early American Settlers (London: Ward, Lock & Tyler, 1853), p.v.

[3] Ibid., p.7.

[4] Ibid, p.11.

[5] Ann Lydia Bond, Three Gems in One Setting (London: W. Kent and Co, 1860).

[6] Northern Daily Times, 24 January, 1861, p.5.

[7] Alastair Fowler, The Mind of the Book: Pictorial Title Pages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p.68.

[8] John Sutherland, The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (New York: Routledge, 2013), p.558.

[9] Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Christina Rossetti and Illustration: A Publishing History (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2002), p.49.

[10] Horace Elisha Scudder, ‘Little Puritans’ in St. Nicolas (London: Scribner & Co, 1879), p.369.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ilana M. Blumberg, Victorian Sacrifice: Ethics and Economics in Mid-Century Novels (Columbus: Ohio State University Press: 2013), p.1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Kate Thompson Sizer, Mayflower Pilgrims (London: Charles H. Kelly, 1898), p.9.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., p.37.

[19] Ibid., p.45.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid. p.46-47.

[22] James W. Baker, Thanksgiving: The Biography of an American Holiday (Durham: University of New Hampshire Press, 2009), p.8-12.

[23] Sizer, p.62-63.

[24] J. S. Bratton, The Impact of Victorian Children’s Fiction (London: Barnes and Noble, 1981), p.11.