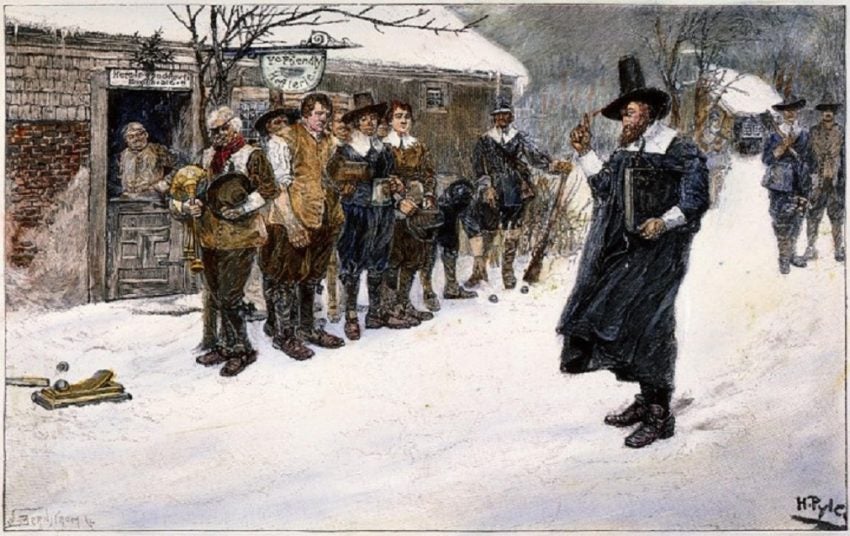

In 1900 the British and American children’s periodical St Nicolas published a short story by leading women’s suffragist and author Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902). Entitled ‘Christmas on the Mayflower’, it included an illustration of the interior of the ship decked out with festive decorations as the Pilgrims sit down to a sumptuous Christmas dinner. Stanton’s story was also rich in details of yule-tide cheer and festivities:

Then the mothers decorated their tables and spread out a grand Christmas dinner. Among other things, they brought a box of plum-puddings. It is an English custom to make a large number of plum-puddings at Christmas-time, and shut them up tight in small tin pails and hang them on hooks on the kitchen wall, where they keep for months. You see them in English kitchens to this day. With their plum-puddings, gooseberry-tarts, Brussels sprouts, salt fish, and bacon, the Pilgrims had quite a sumptuous dinner. Then they sang “God Save the King,” and went on deck to watch the sun go down and the moon rise in all her glory.[1]

Illustration from Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s story ‘Christmas on the Mayflower’ in ‘St Nicolas’ (1900)

Stanton painted a picture of a 1620 Christmas that was familiar to readers in Britain and America. But this rosy scene of pilgrims celebrating with extravagant food and high spirits was a contemporary fiction. Records of the first winter in New Plymouth show us a community on the edge of survival – and Christmas celebrations were scarcely tolerated by Governor William Bradford.

The initial winter in New Plymouth was bleak – nearly half of the colonists died from disease and malnutrition. The first publication from the new colony Mourt’s Relation (1622) makes a brief mention of the very first Christmas amongst the settlers, and it is a scene characterised by hard labour:

Monday, the 25th day, we went on shore, some to fell timber, some to saw, some to rive, and some to carry, so no man rested all that day. But towards night some, as they were at work, heard a noise of some Indians, which caused us all to go to our muskets, but we heard no further. So we came aboard again, and left some twenty to keep the court of guard. That night we had a sore storm of wind and rain.

Monday, the 25 being Christmas day, we began to drink water aboard, but at night the master caused us to have some beer, and so on board we had divers times now and then some beer, but on shore none at all.[2]

The little beer that was procured came the way of the ship’s captain, Christopher Jones (1570-1622), who may not have shared the same antipathy to Christmas as the Brownists on board the Mayflower. Seventeenth-century Puritans did not find any scriptural justification for celebrating Christmas. More seriously, the Puritan community associated such celebrations with both paganism and Roman Catholicism. They particularly objected to rowdy drinking and dancing that could accompany the festivities in England. Such religious opposition to Christmas famously led to a government clampdown on such activities with a 1644 Act of Parliament effectively outlawing the celebration.

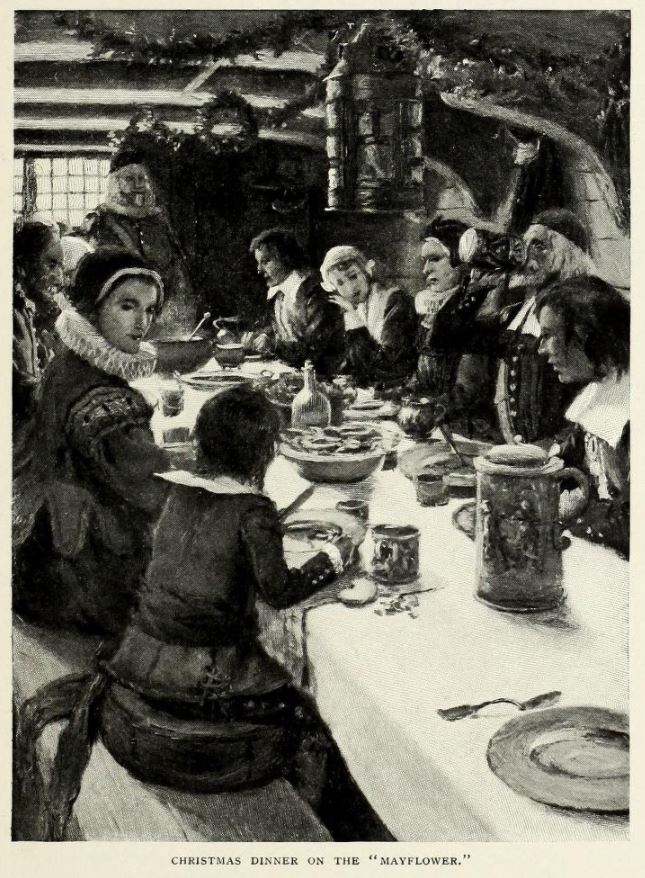

By the winter of 1621 New Plymouth was in a less precarious condition than the previous year. New colonists had recently arrived on the Fortune adding to the number of settlers, though they did not share the religious culture of the Brownists who had disembarked from the Mayflower in 1620. This extended to Christmas and led to some tensions in the fledgling settlement. Bradford recorded this in his journal Of Plimoth Plantation – and he was not best pleased to see that some of the new arrivals had decided to take the day off work on December 25th:

On the day called Christmas day, the Gov called them out to work, (as was used,) but the most of this new-company excused themselves and said it went against their consciences to work on that day. So the Gov told them that if they made it matter of conscience, he would spare them till they were better informed. So he led away the rest and left them.[3]

Initially, Bradford acquiesced to their request for a day of rest – but events took a different turn. Bradford had expected the men to confine their celebrations to their homes, and was aghast to find their distinctly un-Puritan revelry had spilled out onto the streets:

But when they came home at noon from their work, he found them in the street at play, openly; some pitching the bar, and some at stool-ball [a bat and ball game – similar to cricket] and such like sports. So he went to them and took away their implements and told them that was against his conscience, that they should play and others work. If they made the keeping of it matter of devotion, let them keep their houses; but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets. Since which time nothing hath been attempted that way, at least openly.[4]

The image of Bradford taking away the bats and balls of Christmas merrymakers was illustrated by Howard Pyle in his work “The Puritan Governor interrupting the Christmas Sports” (1883). In this picture, Bradford wags a stern figure at the men for such sacrilegious activities – appearing like a schoolteacher telling-off naughty school children. Bradford notes that in the twenty years since the failed merrymaking of 1621 ‘nothing hath been attempted that way, at least openly’. When we look at the historical record we see that Stanton’s picture of open celebrations seems all the more unlikely.

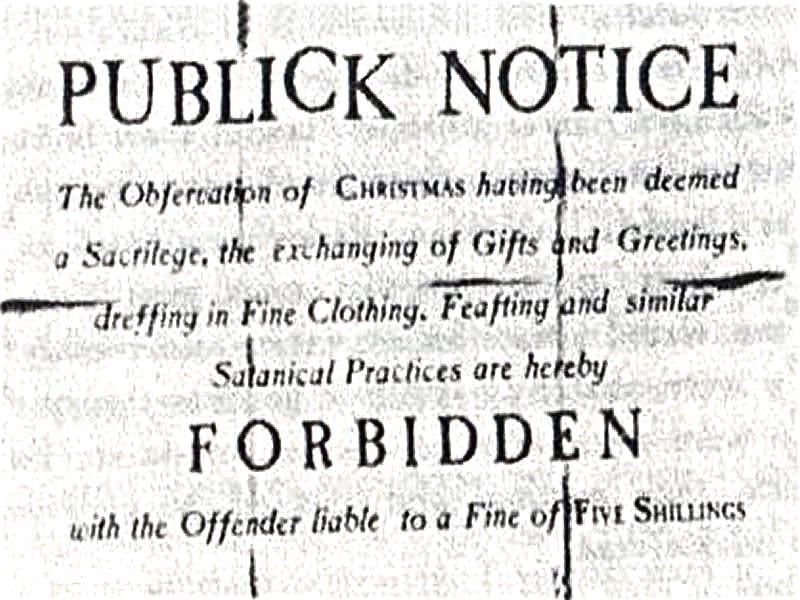

The distaste towards Christmas was felt more widely in New England. In 1659 the Massachusetts Bay Colony officially ruled that observing Christmas was an offense punishable by a 5 shilling fine:

It is therefore Ordered by this Court and the Authority thereof, that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing labour, feasting, or any other way upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending, shall pay for every such offence five shillings as a fine to the County.[5]

Public notices were posted to make sure that people were aware of the rules. Whilst the act was repealed in 1681 the effect on New England culture was long lasting. Until the nineteenth century there was little in the way of Christmas celebrations. Christmas only became an official state holiday in 1856.

By the time Stanton wrote her short Christmas story the celebration was firmly a part of the national culture of both Britain and America. It is no surprise then that writers wished to map their modern enthusiasm for Christmas back on to the past. Stanton even imagined a happy scene of present giving between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims:

The exchanging of presents was a very pretty ceremony, and when they were ready to depart, the good elder placed his hands on each little head, giving a short prayer and his blessing. While all this was transpiring the squaws asked the foremothers to give them beads, which they readily did, and placed wreaths of ivy on their heads. As they paddled away- in their little canoes, the horns and drums sounded.[6]

The scene was fiction – but much of the historical culture of the Mayflower exists between the boundaries of history and myth. J. R. Harris’ discovery of the ‘The Mayflower Barn’, Felicia Hemans’ famous ‘stern and rock bound coast’, and the pageants of the 1920 tercentenary all mixed creativity with history, providing a picture of the past that appealed to the audiences of their era. This creative retelling of the past is an integral part of historical culture, and ‘Christmas on the Mayflower’ is just one more example of the extraordinary ways in which the Pilgrim Fathers have been reinterpreted over the centuries.

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, St Nicolas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks. Part I, November 1900 to April 1901 (London: Macmillian and Co, 1901), p.123.

[2] Dwight B. Heath, Mourt’s Relation: A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1986), p.42.

[3] William Bradford quoted in William Peterfield Trent, Readings from Colonial Prose and Poetry (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1903), p.46.

[4] Ibid.

[5] THE GENERAL LAWS And LIBERTIES Of the MASSACHUSETS COLONY: Revised & Re-printed, By Order of the General Court Holden at Boston. May 15th. 1672 Edward Rawson Sec [https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N00114.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext]

[6] Stanton, p. 123.