*Guest post by Dr Sam Edwards, Manchester Metropolitan University*

As I found out later, the weather was much the same as the day, over 90 years previous, that the monument had been dedicated. The sky was grey, the breeze fresh, and rain threatened. I’d spent the morning cycling around some of the old airfields that still mark the Lincolnshire Wolds, an obsession that’s been with me since I was a teenager. But that day, and largely on a whim, I decided to head home (to family in Grimsby) via a detour to the Humber. I’d been told of a monument in the village of Immingham that might be of interest.

At Immingham I aimed – by instinct – for the church tower, and it was as I neared St. Andrews (fifteenth century in origins) that I saw it: a tall pillar of granite, weathered by decades of coastal storms. Dedicated to the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ who had set sail from ‘this creek’ in 1608, the pillar was clearly the result of some concerted effort. But it was the name of the organisation responsible that drew my attention – the Sulgrave Institution. I’d only recently completed some research at Sulgrave Manor in deepest Northamptonshire and so the question soon arrived: why had those responsible for establishing the Manor as a memorial to George Washington (it was his ancestral home) also erected this pillar near the Humber? What was the connection? Cycling home in the last of the autumn light I decided to resolve the quandary. As I was to learn, the answer lay in a variety of factors which, when combined, ensured that in the post-First World War period Immingham became an attractive location in which – as at Sulgrave – to celebrate the Anglo-American ties of history and memory.

The memorial today (photo by author)

‘A Goode Commone…between Grimsbe and Hull’: The Flight of the Pilgrims

First amongst these factors were the details of history. For whilst the 1620 sailing of the Mayflower to the New World was well-known, it was not in fact the first or only departure of these ‘separatists’ from British shores. Subject to persecution for their religious views, they had first tried to flee from Boston in 1607 only for several of their number to suffer imprisonment. They tried again in 1608, this time from a spot on the Humber, which was near to their stronghold in South Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, and Lincolnshire. They were more successful on this occasion and some – though not all – made it to Holland. But over time the details regarding their exact point of departure were lost, a puzzle that in turn drew increasing attention by the latter nineteenth century.

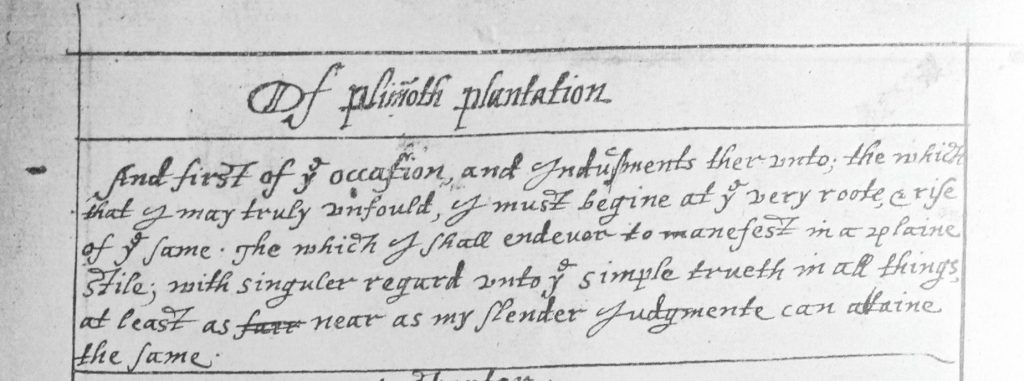

Key to solving the problem was the history written by a leading separatist, William Bradford. Authored in the seventeenth century, this had been lost for many years until it was re-discovered in the Library of the Bishop of London in the 1850s. In 1897 it was then returned to Massachusetts amidst much pomp and ceremony, and in doing so the question of from exactly where the separatists – or ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ as they were now known – had departed gained new attention. Bradford had referred to a spot near a ‘good commone’ ‘betweene Grimsbe and Hull’ and as a result various historians and antiquarians duly endeavoured to identify the most likely location.[1] In time, one local minister claimed Immingham whilst others suggested a site closer to Stallingborough. But by 1914, as war threatened in Europe, it was the idea of an Immingham connection, claimed by a Reverend Reid, which seems to have stuck.[2]

The Immingham Connection and the Centennial of Peace

Reid’s interest was in part a product of the moment. This was an era of ‘rapprochement’ between the United States and Britain, a diplomatic ‘coming together’ informed by contemporary geo-political developments (the rise of Germany) as well as transatlantic investment in a powerful idea – that Britons and Americans were members of a single ‘Anglo-Saxon’ family. Such developments duly encouraged communities in both countries to celebrate specific Anglo-American ties and connections, a project also closely connected to a widely anticipated anniversary – the Centennial of Peace between the ‘English-speaking peoples’. By 1913, the Anglo-American committee planning the Centennial commemorations had developed an ambitious programme, amongst which were various exhibitions and ceremonies as well as the establishment in Britain of several memorials celebrating famous individuals in Anglo-American history (especially Abraham Lincoln and George Washington).[3] It was this latter fact, widely reported in the national press, that likely caught the attention of Reverend Reid. So in 1914 he journeyed to the United States and duly received £2,000 in pledges from wealthy New Yorkers keen to help his particular cause, the restoration of St. Andrew’s church as a memorial to Immingham’s own unique Anglo-American connection – the 1608 flight of the Pilgrim Fathers.[4]

The outbreak of war in Europe then intervened. But interest in the Centennial returned after the Armistice and in relatively quick order several of the memorials first planned back in 1914 were realised, including statues of Abraham Lincoln in Manchester (1919) and London (1920), and a statue of George Washington at Trafalgar Square (1921). In Immingham, too, interest in marking the Pilgrim Fathers similarly returned, now driven by three connected developments: (1) concerns that the Immingham link to the Pilgrim Fathers had been long overshadowed by Plymouth-focused commemorations; (2) the large-scale plans to mark yet another anniversary, the Tercentenary of the Mayflower sailing; (3) the establishment in nearby Hull of a special ‘Anglo-American’ Society, a regional branch of the national organisation formed at Sulgrave in Northamptonshire and which was central to establishing the Washington statue in London.

The Abraham Lincoln statue in Manchester – Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net) – CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Building the Monument

The overall objective, however, had shifted and was now focused on the erection of a monument rather than the restoration of St. Andrew’s church. The origins of this new idea lie in an open-air commemoration held near Immingham in September 1920. The lead orator, a Reverend J.G. Patton, confidently declared Killinghome Creek (just a short distance from Immingham) to be the ‘spot’ where a ‘company of good country folk’ began ‘the most noble historic achievement’ for ‘modern democracy had been born in them’. Later, during a dinner hosted in Hull City Hall by the newly formed Anglo-American Society, the American Consul – J.H. Grout – reciprocated, explaining that the history of the Pilgrim Fathers demonstrated that Americans and Britons were all part of one ‘Anglo-Saxon’ ‘family’.[5]

These assumed connections of place, politics and race were subsequently revisited as plans for the monument – ultimately funded by Hull’s growing middle class – developed. At a 1922 event (again hosted by the Society) one orator declared that the planned monument would celebrate ‘Anglo-American friendship’, whilst during the dedication in July 1924 of the monument’s foundation stone another speaker – Charles Wakefield, a leading member of the national Sulgrave organisation – explained that the Immingham monument would help ‘American visitors to realise what we meant when we talked of kinship’. Wakefield ‘hoped, too, that the monument would help his own countrymen to feel that the attainment of sympathetic understanding of American problems and American contributions towards modern progress was necessary if we were to understand each other’s finest qualities’.[6]

Detail on the monument – copyright Heather Wilkinson Rojo

These latter comments hint at some contemporary tensions. The Washington naval conference of 1921-22 featured at times bitter wrangling between Americans and Britons as the former pursued (successfully) parity with Britannia. On the Humber, moreover, such tensions cut close to the bone: Hull was the country’s third major port and it had a peculiarly strong connection to the US Navy. During the war a US Navy seaplane base had in fact been established at, of all places, Killingholme Creek.[7] Such connections help explain a key feature of the 1924 dedication ceremony: the presence of American and British naval personnel who featured prominently in the proceedings, with all signs of disagreement replaced by declarations of fellowship and friendship.

The unveiling of the completed monument in September 1925 followed the same format. Once again, American and British naval vessels were in attendance and so too was a crew from a Dutch warship, a recognition of the fact that when the Pilgrim Fathers fled in 1608 they went first to Holland. The lead speaker, again Reverend Patton, happily informed his Anglo-American-Dutch audience that the Pilgrims were the ‘noblest type of our race’ who exemplified ‘the English spirit of adventure at its best’. Patton even went so far as to claim that the ‘Constitution of the United States in its fundamental principles was essentially that drawn up in the Mayflower cabin’.[8]

Illustrated London News (26 September 1925), p. 36 – copyright Mary Evans Picture Library

Leeds Mercury – Friday 01 August 1924 – copyright Leeds Mercury/Yorkshire Post

Anglo-American Comradeship in Past and Present

The monument before which Patton stood and around which had gathered a coated crowd shivering in the breeze was impressive in scale. Standing twenty feet in height it had been purposely designed to be seen ‘by all vessels navigating the Humber’. In construction, it was the work of a well-known Hull builder – Edwin Quibell – who used local stone for the base and pillar, atop of which sat ‘a piece of grey granite brought from the identical spot at Plymouth Rock, upon which the Pilgrim Fathers landed’.[9] This latter stone was a gift of American benefactors in Massachusetts and for some contemporaries the fine details thus appear to have been subsequently lost in translation, with the idea later emerging that the capstone was hewed from Plymouth Rock itself. It was not; rather, it was surplus to the construction of a protective and commemorative canopy over Plymouth Rock, a substantive job undertaken in 1920.[10] Regardless, for the Anglo-American Society of Hull the key thing was that the memorial and its granite capstone firmly anchored Immingham into a world of Anglo-American comradeship.

In the years after, the monument certainly drew occasional interest. But as the decades passed it became an increasingly forlorn structure, overshadowed by the infrastructure of the encroaching dock facilities, and so in 1970 it was removed to its present location within sight of St. Andrew’s church. It stands there still today, a granite marker recording the distant events of 1608 and the signpost to a moment – the 1920s – when the good folk of Humberside declared their commitment to the great project of the age: establishing an Anglo-American alliance to secure peace and prosperity for all time to come.

Copyright Heather Wilkinson Rojo

[1] William Bradford, Bradford’s History of Plimouth Plantation, From the Original Manuscript, with a Report of the Proceedings Incident to the Return of the Manuscript to Massachusetts (Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Company, 1899), p. 18.

[2] Hull Daily Mail, 17 April 1914, p. 5.

[3] See British-American Peace Centenary: One Hundred Years of Peace, reprinted from The Times of Tuesday, October 7, 1913, Sulgrave Manor Archives.

[4] Hull Daily Mail, 17 April 1914, p. 5.

[5] Hull Daily Mail, 7 September 1920, p. 5.

[6] Hull Daily Mail, 1 December 1922, p. 4

[7] United States Naval Air Station Killingholme (1918). United States Naval Academy Library. See also Immingham Museum, Killingholme Seaplane Base 1914-1919 (Immingham: Immingham Museum, 1986), pp. 7-9.

[8] See the dedication day programme: Anglo-American Society of Hull, The Pilgrim Fathers’ Monument, Programme of Unveiling Ceremony at Immingham Creek, Thursday, 17 September 1925, HHC.

[9] Hull Daily Mail, 23 May 1924, p. 3.

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 17 January 1941, p. 4; Westminster Gazette, 1 August 1924, p. 3. See also Hull Daily Mail, 16 July 1924, p. 6.