Felicia Hemans was an English poet and literary celebrity whose immense popularity rivalled any writer of the early nineteenth-century, even Lord Byron. Born in Liverpool, her family life was disrupted by the Napoleonic Wars, but her father’s wealth as a wine merchant provided Hemans with a good education at home. Her exceptional talent was noted by a tutor who lamented her gender meant she could not be ‘borne away to the highest honours at college!’.[1] Her first volume of verse Poems (1808), published when Hemans was just 15 from poetry written during her childhood, gained her early notoriety and was to be the first of 24 volumes she would publish in her lifetime. Later, she would find lasting fame on both sides of the Atlantic for her poem ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ (1825).

Hemans attracted much popularity not only in England, but also in Wales, Scotland and America. Her poetry frequently dealt with a growing sense of national feeling and identity, delving into history, myth and folklore for inspiration. For example, she had spent much of her childhood in Wales, and poems such as ‘Taliesin’s Prophecy’ (1822) dealt with many aspects of Welsh legend and folk history, evoking a mythic Bardic past:

A VOICE from time departed yet floats thy hills among,

O Cambria! thus thy prophet bard, thy Taliesin, sung:

“The path of unborn ages is traced upon my soul,

The clouds which mantle things unseen away before me roll […]

Recently literary critic Shawna Lichtenwalner has referred to Hemans’ poetic engagement with Wales as a ‘successful act of Welsh cultural affirmation’ which offers a ‘complex picture of Welsh history and culture’.[2] Hemans also engaged with Scottish folklore, history, and nationalism. Her poem ‘Wallace’s Invocation to Bruce’ (1819) explicitly Romanticises and mythologises Scotland’s war with Edward I of England:

O’er the dark plumes and serried spears

Of Scotland’s daring Mountaineers,

As all elate with hope, they stood,

To buy their freedom with their blood.

Here is an early example of popular national sentiment attached to an emotive evocation of history, one that has found its most popular recent realisation in Mel Gibson’s stunningly successful film Braveheart (1995). ‘Wallace’s Invocation to Bruce’ is also a highly Romantic poem, replete with natural imagery shrouded in mists, and prophetic visions of the future:

Those visions o’er my thought have passed,

Where mountain-vapours darkly roll,

That spirit hath possessed my soul!

And shadowy forms have met mine eye,

The beings of futurity!

And a deep voice of years to be,

Hath told that Scotland shall be free!

It is evident from Hemans’ Welsh and Scottish themed poetry that she was interested in national pasts and ideas about nationhood. Indeed, the growth of popular national identity is often regarded as concurrent with the development of Romanticism itself, referred to in scholarship as ‘Romantic Nationalism’. Hemans’ role in the development of Romantic poetry has only recently been given critical attention. Despite her celebrity and influence, it wasn’t until the 1970s and the ‘feminist turn’ in Romantic scholarship that female poets were given more focus in terms of research and analysis. Up until then, criticism of Romantic poetry had been dominated by the ‘big six’ male poets (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Byron, Shelley, and Blake). Certainly, the contribution Hemans made to the emerging discourse of national identity is one area where more attention needs to be paid. [image from Anne Lydia Bond, Three Gems in One Sitting (London: W. Kent and Co, 1860)]

[image from Anne Lydia Bond, Three Gems in One Sitting (London: W. Kent and Co, 1860)]

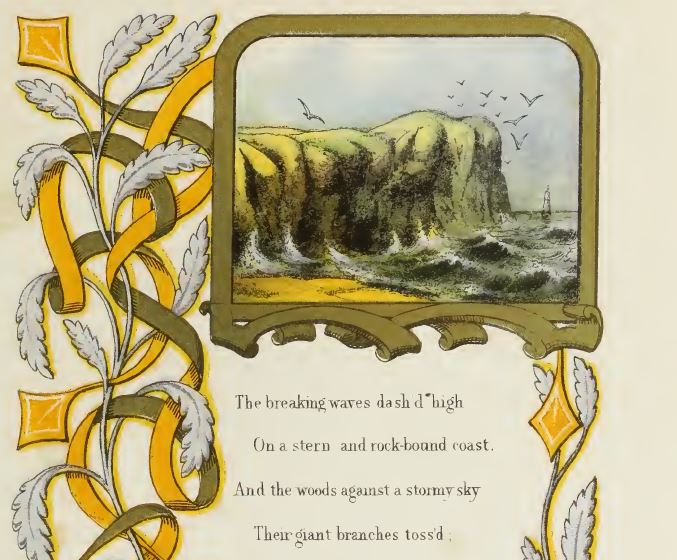

One poem in particular that requires more attention in this regard is Hemans poem ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ (1825). Designed to celebrate the Pilgrim Fathers as an origin myth for the United States, Hemans verse was first published the New Monthly Magazine and circulated in newspapers such as The Morning Post.[3] The poem takes inspiration from David Webster’s celebrated bicentenary oration ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ which Hemans knew and referred to in her notes.[4] Hemans’ poem was a popular success in Britain and the United States. In keeping with much of Hemans’ work, it is a highly Romantic interpretation of the 1620 Atlantic crossing focusing on natural imagery and personal emotion. The opening stanza emphasises the peril of the voyage with dramatic descriptions of an ocean storm:

The breaking waves dash’d high

On a stern and rock-bound coast,

And the woods against a stormy sky

Their giant branches toss’d.

This scene takes place on a ‘dark’ and ‘heavy night’ which combined with imagery of a desolate ‘rock-bound’ coast set again ‘breaking waves’ and a ‘stormy sky’ edges close to high Gothic melodrama. Indeed, as Glen A. Omans comments ‘modern readers may find Hemans’s expression bombastic […] [b]ut contemporaries were charmed’.[5] American audiences in particular were receptive to the poem’s depiction of the colonists and their religious mission, and schoolchildren were frequently taught to memorise the poem well into the twentieth-century. The author James Albert Michener recollected his earliest experiences of poetry in his 1991 memoir The World Is My Home: ‘Starting as a lad in primary school, I was required to learn traditional poems selected by enthusiastic and patriotic teachers […] [I] learned the verse with such tenacity that they reverberate in my memory: “The breaking waves dashed high / On a stern and rock-bound coast”.[6]

[image from Anne Lydia Bond, Three Gems in One Sitting (London: W. Kent and Co, 1860)]

[image from Anne Lydia Bond, Three Gems in One Sitting (London: W. Kent and Co, 1860)]

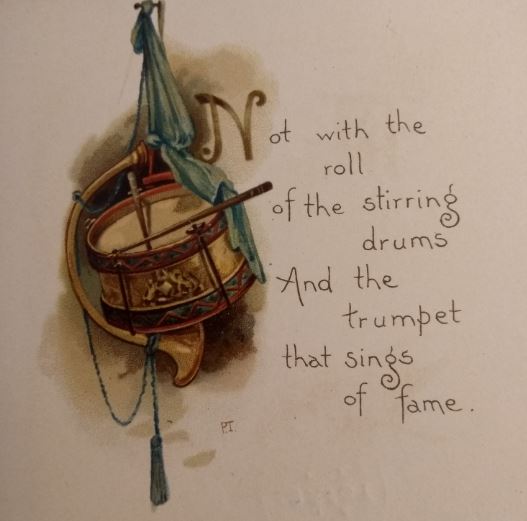

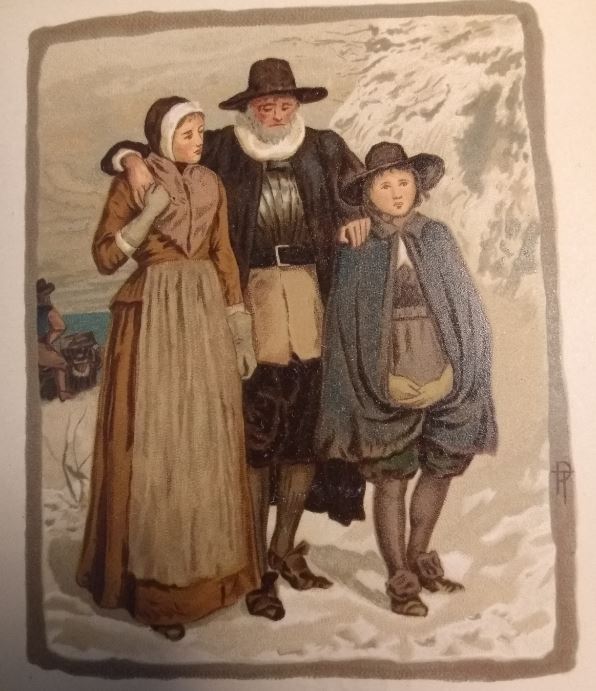

Why was the poem so popular in both Britain and America? One reason was the increased cultural influence the verses gained when the poem was set to music by Hemans composer sister Harriet Browne (1798–1858). It was also published in illustrated editions and gift books. One such example, Anne Lydia Bond’s Three Gems in One Sitting (1860) set Hemans poem alongside Alfred Lloyd Tennyson’s ‘The Poets Song’ and Thomas Campbell’s ‘The Field Flowers’ in a lavishly illustrated collection, which attests to the canonical reputation of the poem.[7] Another example The Breaking Waves Dashed High (The Pilgrim Fathers) went through several editions in America in the 1880s.[8]

[Image from Felicia Hemans, The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers (London: Castell Brothers, 1888)]

[Image from Felicia Hemans, The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers (London: Castell Brothers, 1888)]

But we must also consider the ideological implication of Hemans’ poem to understand why it appealed to a nineteenth-century audience, particularly in the United States where the poem found considerable fame. The poem presents a virtuous picture of colonists that sits uneasily with modern sensibilities, but seems to have had a distinct appeal to the readers of a young nation attempting to define itself and its history. The pilgrims are described as a noble ‘band of exiles’ who arrive in America ‘not as the conqueror comes […] for the trumpet that sings of fame’ but rather to sound ‘the anthem of the free’. Hemans contrasts the Pilgrims with mercantile colonialists; they do they seek ‘Bright jewels of the Mine’, ‘the wealth of seas’ or ‘the spoils of war’. Instead, there’s is a spiritual enterprise for people seeking only the ‘Freedom to worship God’. The religious virtue and moral purity of the ‘Pilgrim fathers’ is central to Hemans poem. The poem is also composed in a traditional hymn form which further heightens the religious inflection. The emotional pathos of the pilgrims is another feature of the work reflected in countless illustrations; these were people who had left ‘their childhood’s land’ and come to a ‘stern and rock-bound coast’ of ‘the wild New-England shore’. This sentimental and Romantic depiction of the pilgrims would influence later American poets such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) whose 1858 poem ‘The Courtship of Miles Standish’ became another popular literary interpretation of the Mayflower pilgrims. Longfellow was an avid fan of Hemans work, going as far as to collect her letters. We can therefore see how Hemans’ short poem cast a long shadow over our modern understanding of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ and their place in history. Indeed, her work shows just how much literature is a driving force behind our appreciation of historical figures and events, and our understanding of nationhood and identity.

[Image from Felicia Hemans, The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers (London: Castell Brothers, 1888)]

[Image from Felicia Hemans, The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers (London: Castell Brothers, 1888)]

[1] Henry Fothergill Chorley, Memorials of Mrs Hemans with Illustrations of her Literary Character from her Private Correspondence (London: Saunders and Otley, 1836), p.20.

[2] Shawna Lichtenwalner, Claiming Cambria: Invoking the Welsh in the Romantic Era (Newark: University of Delaweare Press, 2008), p.150

[3] The Morning Post (London, England), Tuesday, November 01, 1825;

[4] Susan J. Wolfson, Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Letters, Reception Materials (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), p.417.

[5] Glen A. Omans ‘Felicia Hemans’ in Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837: An Encyclopedia ed.by Gerald Newman (New York: Garland Publishing, 1997), p.327.

[6] James Albert Michener, The World Is My Home (New York: The Dial Press, 2007), p.127.

[7] Anne Lydia Bond, Three Gems in One Sitting (London: W. Kent and Co, 1860).

[8] Felicia Hemans, illustrated by L. B. Humphrey, The Breaking Waves Dashed High (The Pilgrim Fathers) (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1883).

I recall my sister memorizing this poem when we were in grade school in the 1950s, in Forks Township, Pennsylvania. It sure is nice that a computer can serve to locate this website when all I remembered was the first two lines and the poet’s first name. It is sad that I was, until this moment, unaware of Heman’s body of work and her “lost” fame. Thank you for providing the above information.

Thank you for sharing that memory with us, Kathy! It’s fascinating to hear that the poem had such a long afterlife, and we are glad that we could give you more information about its origins too.