“Poetry, is impassioned truth; and why should we not utter it in the shape that touches our condition the most closely — the political?” – Ebenezer Elliott

Wood engraving of Ebenezer Elliott from Howitt’s Journal published 3 April 1847 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Dickens reflected on the life of impassioned political reformer and poet Ebenezer Elliott (1781-1849) shortly after his death:

THE name of EBENEZER ELLIOTT is associated with one of the greatest and most important political changes of modern times, with events not yet sufficiently removed from us, to allow of their being canvassed in this place with that freedom which would serve the more fully to illustrate his real merits. Elliott would have been a poet, in all that constitutes true poetry, had the corn laws never existed.[1]

As Dickens notes, Elliott was both a well-known poet and political figure who worked tirelessly for the alleviation of the labouring poor with his writing. Commending his literary as much as his political skill, Dickens praised Elliott’s verses for their ‘tone of sincerity and earnestness—that fire and frenzy which they breathed, and which sent them, hot, burning words of denunciation and wrath, into the bosoms of the working classes—the toiling millions from whom Elliott sprang’.[2] Elliot was an active participant in the Chartist movement and the Anti-Corn Law campaign which earned him the title of the ‘Corn Law rhymer’. His poetry was central to the development of Chartist verse, with Martha Vicinus referring to Elliot as the ‘single most important predecessor of Chartist poets’.[3] Elliott’s poetry was popular amongst readers sympathetic to political reform and helped encourage working-class poetry in the burgeoning Chartist movement.[4] By the end of his life Elliot’s status was such that even his enemies in the Tory press had to recognise his power as a poet and political activist. Writing in 1850, The Spectator, though resistive to Elliott’s ‘vulgar’ and ‘violent diatribes in verse’, acquiesced that Elliot ‘had more genius, power, pathos, and delicacy, than any “poet from the people” except Burns’.[5]

Early nineteenth-century iron foundry similar to that with which Elliott worked. Engraving from J.G. Green, A Short History of the English people (1893), p.1763.

Elliott’s life began with a difficult childhood. He contracted small-pox at age six, which left him ‘fearfully disfigured and six weeks blind’.[6] After a unhappy time spent at Hollis School in Rotherham where he was ‘taught to write and little more’ he began work at his father’s iron foundry. He was paid little and found the work gruelling. Moreover, Elliot’s relationship with his father was fraught with difficulties. Known as the ‘Devil Elliott’ for his fiery Calvinist sermons and iron smelting business in Masbrough near Rotherham, Elliott described his father as ‘a little, broad-set, ill-favoured man’.[7] Writing after his death John Watkins suggested that ‘[t]he stern trade of this iron and steel man had its influence in the formation of his character, and imparted a strong tone to that of his son’.[8] Certainly, Elliott never lost his sympathy for the labouring poor with whom he worked. As the Friends Intelligencer summarized:

[Elliot] was, from his youth up, an uncompromising radical reformer, an eloquent, satirical man, unprepossessing in appearance, but endowed with a grim kind of humour and the power of attracting to himself to men of similar, though usually less definite, opinions.[9]

This activism saw his stern opposition to the Corn Laws which imposed taxes on imports of grain into Britain, thus raising the price of food. The labouring poor, who survived on meagre wages, were highly sensitive to increases in bread prices. Elliott’s poetic opposition to the Corn Laws in The Village Patriarch (1829), The Ranter (1830) and the Corn Law Rhymes (1831) saw him become a well-known figure. His poems gained him international recognition and his most celebrated work ‘The People’s Anthem’ became a radical standard. A direct satire of the God Save the Queen, it argues for a more equal nation free from hierarchy:

When wilt thou save the people?

Oh, God of mercy! when?

Not kings and lords, but nations!

Not thrones and crowns, but men!

Flowers of thy heart, oh, God, are they!

Let them not pass, like weeds, away!

Their heritage a sunless day!

God! save the people! [10]

The fierce anti-monarchical elements expressed in this poem may well be what first attracted Elliott to the story of the Pilgrim Fathers.

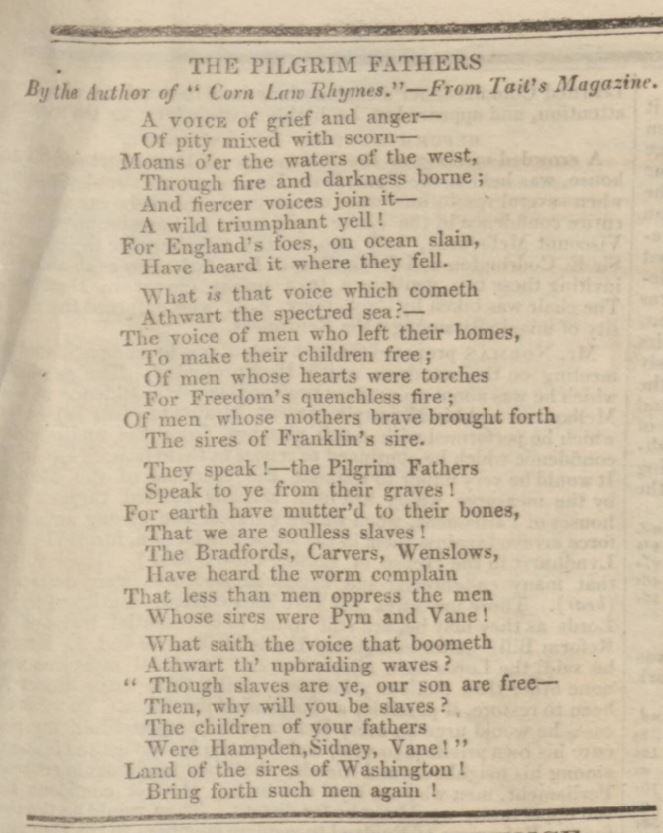

Popularised by Felicia Hemans’ well-known poem and song ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ the narrative was an apposite choice for Elliott, whose works aimed at a broad and popular audience. First published in the pro-reform Tait’s Magazine in 1836 ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ is a searing condemnation of political failures in Britain.[11] Martha Vicinus describes Elliott’s poetry as characterised by ‘emotional bombast’, ‘fervid language’, and ‘urgent appeals to God’.[12] ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ contains all these elements. Elliott provides a fiery invective that castigates modern Britain written in the voice of the Pilgrim Fathers speaking from across the Atlantic:

A VOICE of grief and anger—

Of pity mixed with scorn—

Moans o’er the waters of the west,

Thro’ fire and darkness borne;

And fiercer voices join it—

A wild triumphant yell!

For England’s foes, on ocean slain,

Have heard it where they fell.

What is that voice which cometh

Across the sceptred sea? —

The voice of men who left their homes

To make their children free.

Of men whose hearts were torches

For Freedom’s quenchless fire;

Of men whose mothers have brought forth

The sire of Franklin’s sire.

They speak! The Pilgrim Fathers

Speak to ye from their graves!

For earth hath muttered to their bones

That we are soulless slaves!

The Bradfords, Carvers, and Penslaws,

Have heard the worm complain

That less than men oppress the men

Whose sires were Pym and Vane!

What saith the voice which boometh

Athwart the upbraiding waves? —

“Tho’ slaves are ye, our sons are free—

Then why will you be slaves?

The children of your fathers

Were Hampden, Sidney, Vane!”

Land of the sires of Washington,

Bring forth such men again! [13]

Using the origin myth of the Mayflower, the United States is positioned as a land of freedom in stark contrast with modern Britain. Speaking from the grave, the Pilgrim Fathers are disturbed to find the people of their homeland reduced to ‘soulless slaves’. Elliott makes direct use of William Bradford and John Carver (the first signatory of the Mayflower Compact) as historical figures to articulate his argument for political reform. Describing modern Britons as ‘slaves’ they announce that their ‘sons are free’. The Pilgrim Fathers are positioned as radical freedom-fighters, ‘men whose hearts were torches / For freedom’s quenchless fire’.[14] Whilst clearly ahistorical, Elliott is working in the tradition of British radicalism that stretched back to the fiery oratory and poetry of John Thelwall following the French Revolution. From this perspective, ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ utilises traditional radical vocabulary and invective to agitate for parliamentary reform. As Nigel Cross comments, Elliott wrote ‘unrepentant political poetry, exhorting the working classes to commit themselves to the struggle against landlords, employers, and governments’.[15] By leveraging the story of the Mayflower for the ends of British radicalism, Elliott demonstrates the malleability of Pilgrim Fathers as a cultural narrative.

The poem was a success. Quickly republished in the Leeds Times, the Western Times, the Brighton Patriot, and the Leicester Chronicle, the poem went on to be reprinted throughout the century in radical newspapers. Indeed, its suitability as a vehicle for reform was noted by Leicester Chronicle:

In the last number of Tait’s Magazine, we have a ‘voice’ from the shades of our forefathers, who preferred to trust themselves to the uncultivated wilds of America than to the despotism of a Stuart. This ‘Voice’ was heard by EBENEZER ELLIOTT, in one of his moments of poetic inspiration: and he has echoed the spirit stirring cry to the millions of these isles, clothed in his own immortal verse.[16]

As noted above, Elliott’s skill was in writing poetry that could appeal to a mass audience: ‘the millions of these isles’. This provides an important indication of the growth of popular knowledge regarding the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’. Elliott evidently considered the Mayflower story an appropriate subject for popular political agitation; something familiar to many people. In doing so he promotes the ideal of the Pilgrim Fathers as figures of liberty – fighting against oppression, in order to castigate modern Britain.

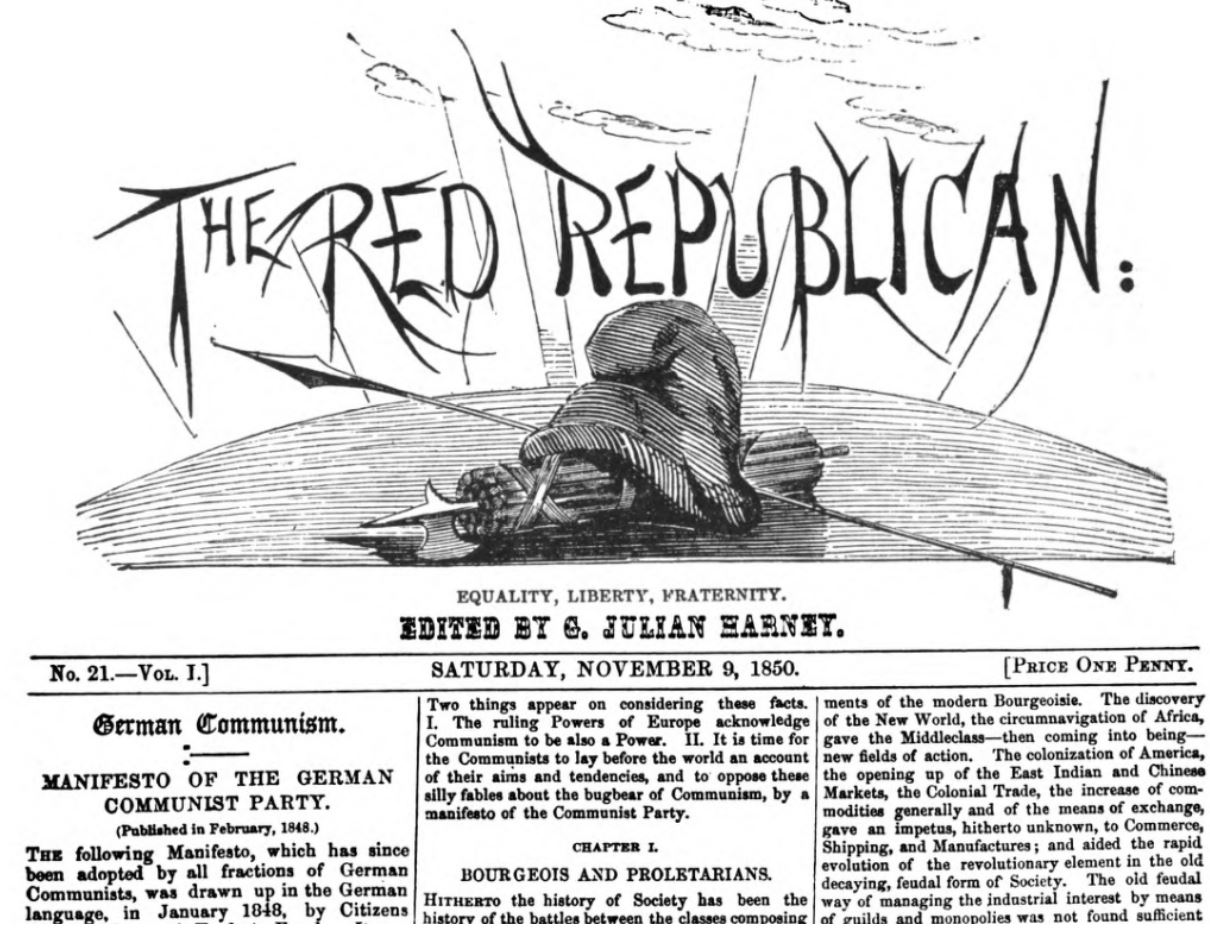

Later in the century Elliott’s verses continued to play a significant role in British radicalism. In the 1840s ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ was reprinted in woks such as John Cleaves’ (1790-1847) The English Chartist Circular.[17] In the 1850s the poem was put to even more radical uses in The Red Republican. This was a socialist newspaper founded by George Julian Harney (1817-1897) after he left the Northern Star (its owner, Feargus O’Connor disagreed with Harney‘s radical socialism). The short run of The Red Republican was notable for publishing the first English translation of the Communist Manifesto by Scottish socialist and feminist Helen Macfarlane (1818-1860).[18] The very same edition of The Red Republican carried Elliott’s ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ in a feature entitled ‘Poetry for the People’ along with words from Ralph Waldo Emerson heightening the revolutionary potential of his poetry:

What is man born for but to be a reformer, a remaker of what man has made; a renouncer of falsehood; a restorer of truth and good; imitating that great Nature that embosoms us all, and which sleeps no moment on an old past, but every hour repairs herself, yielding us every morning a new day, and with every pulsation a new life! [19]

Elliott’s success as a radical author had a significant influence on the recognition of labouring-class poetry more generally. Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) addressed Elliott’s writing directly in the Edinburgh Review; the leading literary periodical of the period. Carlyle’s appraisal was positive, and in his typical rhetorical style he argued that Elliott’s talent should change the reading public’s appreciation of poetry that originated from a ‘quite unmoneyed, russet-coated speaker’:

To some the wonder and interest will be heightened by another circumstance: that the speaker in question is not school-learned, or even furnished with pecuniary capital; is, indeed, a quite unmoneyed, russet-coated speaker; nothing or little other than a Sheffield worker in brass and iron, who describes himself as ‘one of the lower, little removed above the lowest class’. Be of what class he may, the man is provided, as we can perceive, with a rational god-created soul; which too has fashioned itself into some clearness, some self-subsistence, and can actually see and know with its own organs; and in rugged substantial English, nay with tones of poetic melody, utter forth what it has seen.

It used to be said that lions so not paint, that poor men do not write; but the case is altering now. Here is a voice coming from the deep Cyclopean forges, where Labour, in real soot and sweat, beats with thousand hammers ‘the red son of the furnace’; doing personal battle with Necessity, and her dark brute Powers, to make them reasonable and serviceable; and intelligible voice from the hitherto Mute and Irrational, to tell us at first hand how it is with him, what in very deed is the theorem of the world and of himself, which he, in those dim depths of his, in that wearied head of his, has put together. To which voice, in several respects significant enough, let good ear be given.[20]

There are clearly elements of classism still present in Carlyle’s assessment of Elliott’s poetry. However, what is also notable is Carlyle’s deep respect for ‘a voice coming from the deep Cyclopean forges’ (referencing Elliott’s work in an iron foundry) which ‘beats with a thousand hammers’. Dismissive of his radical politics, which he did not share, Carlyle still acknowledged the power and influence of Elliott’s verse in providing a voice for the oppressed. What is more, Elliott’s use of the Pilgrim Fathers shows how the Mayflower narrative became embedded in the Chartist movement and calls for political reform throughout the nineteenth century.

[1] Charles Dickens, ‘Ebenezer Elliott’ Household Words (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1850), p.310.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Martha Vicinus, The Industrial Muse: A Study of Nineteenth-Century British Working-Class Literature (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1974), p.96.

[4] Ibid., p.27.

[5] The Spectator, 10 August, 1850, p.18.

[6] Francis Watt,’ Ebenezer Elliott’ in Stephen, Leslie (ed.) Dictionary of National Biography. Vol 17. (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1889), pp. 266–268.

[7] Ebenezer Elliott, quoted in John Storey, Selected Poetry of Ebenezer Elliott (Cranbury: Associated University Press, 2010), p.14.

[8] John Watkins, Life, Poetry, and Letters of Ebenezer Elliott, with an Abstract of his Politics (London: John Mortimer, 1850), p.30.

[9] Friends’ Intelligencer, Vol 39, (Philadelphia: John Comly, 1886), p.628.

[10] Ebenezer Elliott, The Poetical Works of Ebenezer Elliott , Vol 2 (London: Henry S. King, 1876), pp.202-203.

[11] Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine for 1836, Volume III (Edinburgh: William Tate, Edinburgh) p.573.

[12] Vicinus, p.27.

[13] Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, p.573.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Nigel Cross, The Common Writer: Life in Nineteenth-Century Grub Street (Cambridge: Cambridge university Press, 1985), p.149.

[16] Leicester Chronicle, 10 September, 1836 p.4.

[17] The English Chartist Circular and Temperance Record for England and Wales (New York: A.M. Kelley, 1968), p.382.

[18] The Red Republican, November 9, 1850, p.1.

[19] The Red Republican, November 9, 1850, p.8.

[20] Thomas Carlyle, Carlyle’s Works: Miscellaneous Essays Vol IV (Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 1896), p. p.122.

Will soon be adding a link to this article on my Ebenezer Elliott website. Hope that’s ok.

http://www.judandk.force9.co.uk/elly.htm

The link will be added on the poetry pages