Men they were who could not bend

Blest Pilgrims, surely, as they took for guide

A will by sovereign Conscience sanctified

Late in life, the leading poet of the Romantic period William Wordsworth turned his attention to the Pilgrim Fathers. Felicia Hemans, a second-generation Romantic poet, had already established the story as a popular poem on both sides of the Atlantic. This may be one reason why Wordsworth was keen to provide his own poetic interpretation of the story; certainly his American publisher Henry Reed (1808 – 1854) was keen for Wordsworth to write on the subject. Reed wrote to the famous the poet in 1842 suggesting the suitability of the story of the Pilgrims for a new edition of Ecclesiastical Sketches; Wordsworth responded affirmatively:

I have sent you three sonnets upon certain Aspects of Christianity in America, having as you will see a reference to the subject upon which you wished me to write. I wish they had been more worthy of the subject; I hope, however, you will not disapprove of the connection, which I have thought myself warranted in tracing, between the Puritan fugitives and Episcopacy.[1]

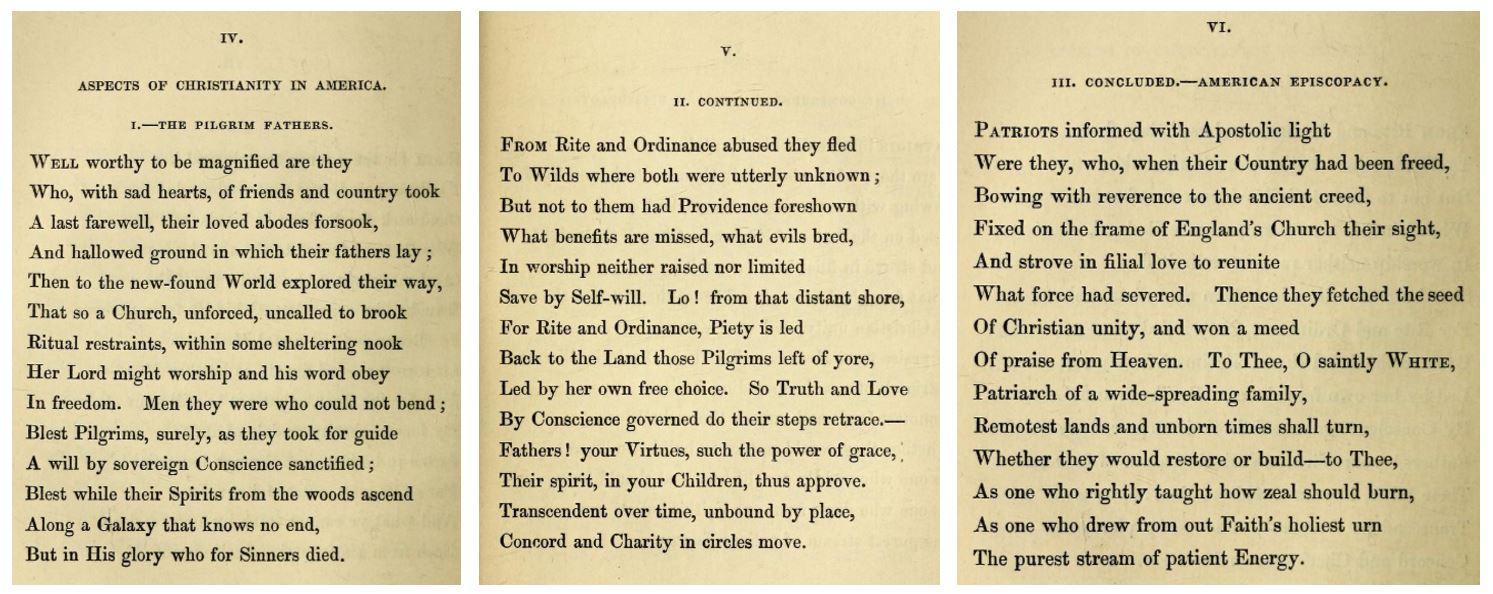

‘Aspects of Christianity in America. The Pilgrim Fathers’ is a three-sonnet sequence which first appeared in Wordsworth’s 1842 publication Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years.[2] Composed the same year, the manuscript copy of the poem is now housed by the Wordsworth Trust,[3] which contains the manuscripts of many new works composed for appearance in Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years.[4]

‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ was also included in an 1842 edition of Ecclesiastical Sketches, which was the original intention for the poem.[5] Wordsworth’s ecclesiastical works have never been hugely popular with the reading pubic or academics, receiving relatively little in the way of anthologisation or scholarly attention. However, in terms of Britain’s contribution to the Mayflower story, Anglo-American literary history, and the intersection between Romanticism and the Pilgrim Fathers more generally, this is a highly significant work of poetry.

For one, Reed was highly enthusiastic in his response to the work, noting the links the poetical sequence draws between the Church of England and the American Episcopal Church:

I have been much impressed with the display of imagination, in one of its important modes of action, in the unity that is given in these poems to the events (running through more than a century and a half) from the migration of the Puritans to the Western world down to the return of the American divines seeking consecration from the Church of England.[6]

The poem emphasises an Anglo-American religious history from the first Puritan Pilgrims of New England to the recent consecration of American bishops at Lambeth in London. As literary scholar Abbie Findlay Potts notes, reunion is a central theme for the work and ‘the peril of schism is forgotten when the American divines return for their consecration at Lambeth’.[7] However, as their inclusion in Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years demonstrates, the poems were published and read outside of the immediate context of Wordsworth’s Ecclesiastical Sketches. Their inclusion in Albert Christopher Addison’s The Romantic Story of the Mayflower Pilgrims (1911) (pictured below) shows the continued relevance of these works to a British audience and the development of the Mayflower story beyond the nineteenth century.

The first poem is an elegiac tribute to the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ and proclaims the men ‘well worthy to be magnified’ for their accomplishments. Wordsworth overtly romanticises the story of the Pilgrims; there is a clear focus on the emotions felt by the travellers for their ‘loved abodes’ and ‘the hallowed ground in which their fathers lay’. They leave England with ‘with sad hearts’ and offer a ‘last farewell’ to their ‘friends and country’. Their home is ‘forsook’ in exchange for ‘a new-found World’ and ‘some sheltering nook’ within which they may ‘worship […] in freedom’. The poem concludes with a combination of natural and religious imagery celebrating the sanctifying Christian virtues brought to America by the Pilgrims:

A will by sovereign Conscience sanctified

Blest while their spirits from woods ascend

Along a galaxy that knows no end

But in His glory who for sinners died

The second poem begins with a celebration of the independent spirit of the Pilgrims who fled from ‘Rite and Ordinance abused’ and into ‘[w]ilds where both were utterly unknown’. They persevere through ‘free choice’ and ‘Self-Will’; however, the mid-point of the second sonnet sees the colonists return to the English religious community which they had left. Wordsworth writes how the Pilgrims, by ‘Conscience Governed […] their steps retrace’ and they complete a journey ‘Back to the Land […] left of Yore’. The second sonnet closes triumphantly with ‘Concord and Charity’ shown to be ‘Transcendent over time’. The final sonnet completes the reunification. Wordsworth writes how ‘filial love’ and ‘Apostolic light’ have achieved a new ‘Christian unity’ in the nineteenth century. The sonnet then imagines future connections where ‘[r]emotest lands and unborn times shall turn’ back to ‘England’s Church’. The Pilgrims are praised for the rejuvenating and unifying spirit of Christianity brought back to England.

This theme of reconciliation and healing was something that Wordsworth was keenly interested in during the social unrest of the ‘hungry forties’. Wordsworth’s celebrity grew over his lifetime, and in the final decade of his life he was recognised as a poet of great spiritual and social importance to the nation, becoming the poet laureate in 1843. This growing public role was something that Wordsworth responded to in his writing from this period. As Stephen Gill notes, his last separate volume of poetry Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years was ‘presented in 1842 as a contribution to social healing’.[8] ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ can be read as a work keenly invested in ‘social healing’ not just in Britain, but between the United Kingdom and the United States, helping to heal the rupture between the two nations after the American War of Independence. In this way, Wordsworth’s poem anticipates the role the Mayflower story would play in Anglo-American diplomacy over the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Although little known today, contemporary reaction to the ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ was favourable. An American publication The Church Record, and Protestant Episcopalian made the following assessment of Wordsworth’s poetic sequence:

These last three sonnets may be advantageously compared with the best of the preceding. They contain purely natural thoughts, expressed with a noble simplicity. Their very finished structure detracts from any sense of striking simplicity, but impresses them more distinctly on the reader’s mind and heart. Though now an old man, we trust the poet of the Church of England may live man years yet, to write sonnets like these; and to delight the lovers of pure poetry and grand genius, with these beautiful flowers of fancy, he emanations of an innocent heart and a rich imagination, forming a glorious chaplet and wreath for the Christian Bard.[9]

Reed’s hope that the poems may appeal to an American audience is evident here. In more general terms, Wordsworth’s contribution to the Mayflower story shows how important the story had become to British authors in the mid-nineteenth century, and the intimate connection between the narrative and leading Romantic poets.

The three sonney sequence as it appears in Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years (London: Edward Moxon, 1842), pp. 218-220.

[1] William Wordsworth, The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Vol. 7: The Later Years: Part IV: 1840–1853 ed. by Ernest De Selincourt and Alan G. Hill (Oxford: University of Oxford, 1967), p.297.

[2] William Wordsworth, Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years: Including The Borderers, a Tragedy (London: Edward Moxon, 1842), pp.218-220.

[3]DCMS 151, The Wordsworth Trust http://collections.wordsworth.org.uk/wtweb/home.asp?page=linked%20item&objectidentity=DCMS%20151

[4] Ibid.

[5] Publication noted in 1842 edition The Church Record, and Protestant Episcopalian – original source needed.

[6] Henry Reed, quoted in Abbie Findlay Potts, The Ecclesiastical Sonnets of William Wordsworth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1922), p.55.

[7] Potts, p.69.

[8] Stephen Gill, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 Vol. 33, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (Autumn, 1993), 841-858 (p.845).

[9] The Church Record, and Protestant Episcopalian, Volume 1, New York, October, 1842.