In other blogs we have written about how the Pilgrims became the muse of Romantic artists and authors in the early nineteenth century, such as the poets Felicia Hemans and William Wordsworth. Yet many of the details of the actual history of the former lives of the Separatists – their homes and places of worship in the Old England – remained vague or unknown to the early Victorians. In this post, we investigate how some of the gaps in knowledge were filled in, and the vital role played by a now mostly forgotten English antiquarian: Joseph Hunter.

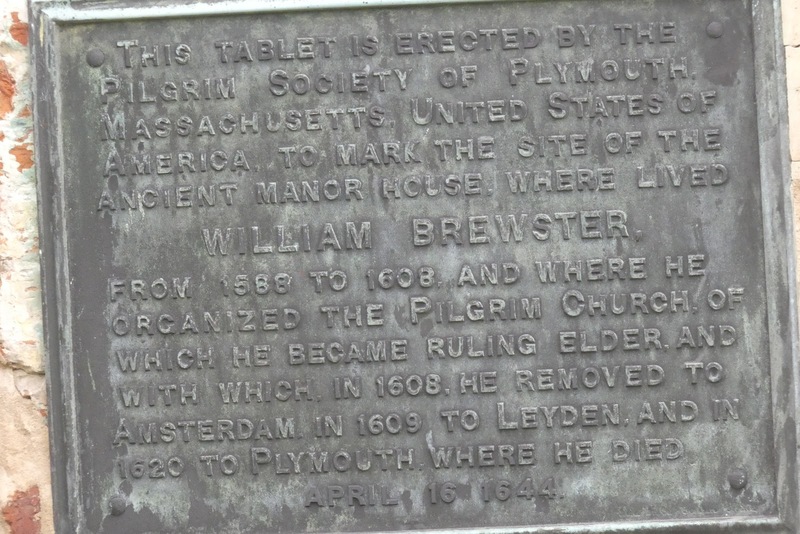

None of the later 17th and 18th century New England chroniclers, such as Nathanial Morton or Cotton Mather, had named Scrooby, a small village in Nottinghamshire, as a place of interest in the story of the Pilgrims. Each had drawn primarily on the unpublished manuscript history of New Plymouth by the colony’s second governor William Bradford, who was imprecise about some of the specific whereabouts. The only clues he gave, in different parts of his work, were how the group was made up of ‘several religious people near the joining borders of Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire’ and how they had met at William Brewster’s ‘house’, which was a ‘manor of the bishop’s’. These early chroniclers either did not know or, perhaps more likely, saw the exact location of this ‘manor’ as being relatively unimportant in explaining the Puritan plantation.

But, in the 1840s, Alexander Young’s Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers (Boston, 1841) brought a new curiosity to this question. Young compiled some of the key original texts from the 17th century, like Edward Winslow’s Good Newes from New England (1624), alongside as yet unpublished sections of Bradford’s by then missing manuscript. Many of the chronological and geographic details about the Pilgrims’ travails in England were already – technically, at least – a matter of public record, but Young’s book encouraged more thought about the Pilgrim’s ‘rise in the north of England… [and] their persecutions there’. One year later, James Savage, an influential American antiquarian from Boston, was in England undertaking genealogical research. During that trip, an antiquarian called Joseph Hunter gave Savage an early inclination that William Bradford was born in Austerfield rather than Ansterfield – the place that had been incorrectly named by Cotton Mather in Magnalia Christi Americana, or the Ecclesiastical History of New England (1702).

Given the totemic place that the Pilgrims were starting to take in the mythology of the founding of the United States, a desire to learn about their origins was now beginning to grow. Savage’s findings were published in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1843 and, two years later, the New England Historic Genealogical Society was formed. In the first issue of their journal in 1847, they acknowledged its creation was a response to ‘an awakened’ and ‘growing interest’ in the ‘knowledge’ that could be garnered from genealogical investigations – including those into the Pilgrims. Joseph Hunter was well aware too of the awareness of ‘these fathers of the Anglo-American race’, and how Americans ‘cherish[ed] an affection and cultivate[d] respect for the land from which their forefathers in sorrow departed, and who, should a great political necessity arise, would be found to stand side by side’ with Britons ‘in the assertion of the just rights of men.’ Like other Victorians, Hunter was drawing on the cultural purchase of a loosely racialised sense of lineage and ancestry – one that connected the British Empire to the power of its most famous daughter, the United States.

Hunter is little remembered today, but he was undoubtedly an important figure in early Victorian antiquarianism. He was born in Sheffield in 1783 and, after his mother died, was placed under the guardianship of Rev Joseph Evans, a family friend and minister of a congregation of Presbyterian dissenters. From an early age he was fascinated by history, topography and genealogy, pursuits that he nurtured as he began his own career as a minister at Bath in 1809. He was already publishing prolifically on a huge variety of topics by the 1820s, and the next decade was appointed the Assistant Keeper of the First Class for the Public Records in London. As a nonconformist and antiquarian, he unsurprisingly had an interest in his own history. In 1846 he published an investigation of eleven generations of his ‘Puritan family’ as a form of ‘monument’ to ‘the many good and religious persons who form[ed] the lines’ from which he ‘spr[a]ng’. For Hunter, there were ‘few studies more instructive’ than ‘ancestry’; as he put it, ‘We know better what we are, when we know what they have been’. Given his special expertise in the local history of Yorkshire and the Midlands, combined with his clear genealogical expertise and religious beliefs, it is unsurprising that he became tied up in the pursuit of Pilgrim ancestry. Spurred on by American interest in the early 1840s, he began to investigate more determinedly.

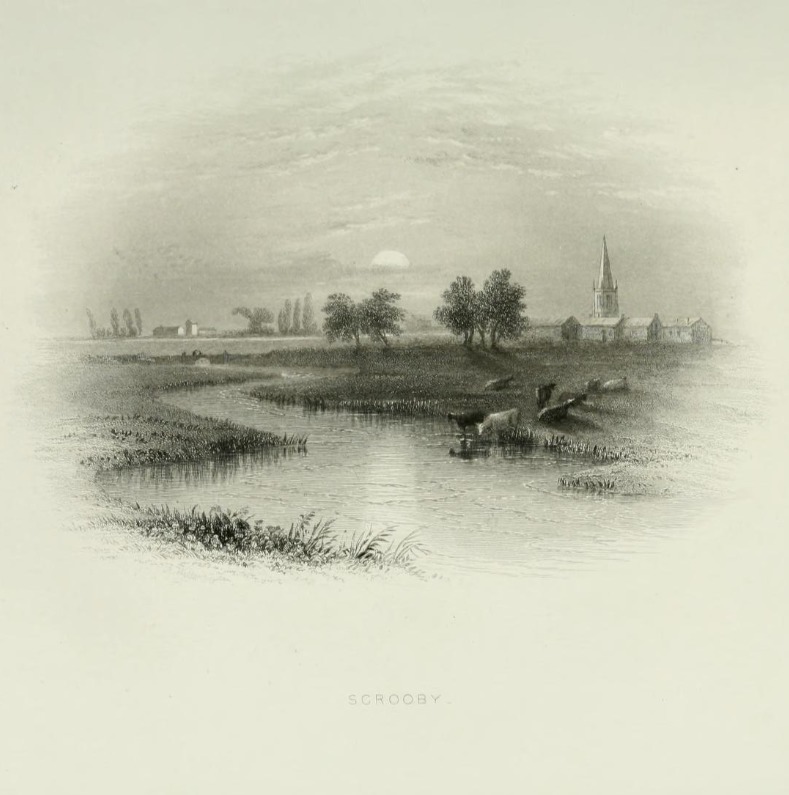

Scrooby – William Henry Bartlett, The Pilgrim Fathers, or, The Founders of New England in the Reign of James the First (London, 1854).

Marcus Bourne Huish, The American Pilgrim’s Way in England to Homes and Memorials of the Founders of Virginia, the New England States and Pennsylvania (London: 1907).

At the end of the decade, Hunter published his Collections concerning the Early History of the Founders of New Plymouth, the First Colonists of New England (1849). Using Bradford’s own words, he used deduction and original archival material to pinpoint Scrooby as the home of the early congregation. The key to his discovery was reinterpreting the meaning of ‘manor’ in Bradford’s history. Rather than it being ‘commonly used to denote’ a ‘district throughout which certain feudal privileges are enjoyed’ – the definition he suspected had been used by American authors – it instead meant a ‘mansion’. Hunter, with ‘confidence’, argued that there was ‘no other episcopal manor’ but Scrooby that ‘satisfie[d] the condition of being near the borders of the three counties’. He then demonstrated that Brewster had been assessed to a subsidy granted by Queen Elizabeth in ‘Scrooby-cum-Ranskill’, and that, in 1608, when he was fined by the commissioners for ecclesiastical causes’ he was also described as being of Scrooby. Without a shadow of a doubt, Hunter had successfully found the Pilgrim’s early place of worship.

Hunter’s discovery caused quite a stir both in England, where he found ‘the new facts eagerly accepted and reproduced’, and in New England, where he was invited to again contribute to the transactions of the Massachusetts Historical Society. He published a much-expanded version of his work in 1854, Collections concerning the Church or Congregation of Protestant Separatists formed at Scrooby in North Nottinghamshire…. and just the next year was again at the forefront of an unfolding exciting discovery. In 1855, the American historian and reverend John Barry was tipped off about a reference to a ‘MS. History of the Planation of Plymouth… in the Fulham Library’ in an 1846 work by Samuel Wilberforce (Bishop of Oxford). Wilberforce, he concluded, must have had access to the supposedly lost Bradford manuscript (stolen, it seems likely, by British troops during the War of Independence). Barry told Charles Deane, a Boston-based merchant and antiquarian, who promptly contacted Hunter in England. Hunter authenticated the manuscript held in the Bishop of London’s Fulham Palace, and made a transcript that was published in 1856 – undoubtedly the most important source for the early history of the New Plymouth colony.

By the late 19th century, Scrooby was a key point on the Pilgrim trail – as it still is today. It has accumulated plaques from American descendant societies and international Congregationalist conferences, and featured in the illustrated travel guides of artists like William Henry Bartlett. Yet, for over 200 years, all knowledge of the important role this sleepy village had played had been forgotten; it took the joining of Victorian genealogical interests across the Atlantic, and the careful work of one English antiquarian, to bring it to light.

Material Used

Joseph Hunter, Gens Sylvestrina: Memorials of some of my good and religious ancestors, or eleven generations of a Puritan family (London, 1846).

A Brief Memoir of the late Joseph Hunter, FSA (London, 1861).

‘Gleanings for New England History’, Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, series 3 volume 8 (1843), 56-8.

The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, vol. 1 (1847), iv.

Joseph Hunter, Collections concerning the Church or Congregation of Protestant Separatists formed at Scrooby in North Nottinghamshire in the Time of King JamesI: The Foudners of New Plymouth the Parent Colony of New England (1854)

William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, ed. Charles Deane (Boston, 1856), 24.