Historical pageants were, at one time, the most popular form of engagement with the past in Britain. Bursting onto the social stage in 1905, they took place across the country and the Empire, from the smallest villages to the largest cities. Amateur casts up to 10,000 people – and that is not a typo – were brought together by ingenious ‘pageant-masters’ to perform their local history, and audiences of up to 100,000 packed themselves into outdoor arenas and fields to spectate. In the early days of the ‘pageantitis’ pandemic, the storyline of pageants usually began in the dim and distant past of ancient Celtic Britain, before the arrival of the Romans heralded the beginnings of civilisation. Following episodes cycled through the conquering Saxons and Normans, then the different monarchical reigns from Tudor to Elizabethan. Usually ending with good old Queen Bess, these romantic re-enactments told a story of local and national progress: the setting of historical foundations for great power in the present. Continue reading

Mayflower Stories

Mayflower Travel Writing in Britain

The Mayflower Pilgrims – A Voyage Out of Context

*Guest post by Adrian Gray, historical adviser to Bassetlaw Christian Heritage and director of Pilgrims & Prophets Christian Heritage Tours*

Growing up in Lincolnshire and now living just on the Nottinghamshire side of the border, I’ve long been aware of the ‘Mayflower’ story but have also noticed that its local impact has been small. In the Scrooby/Gainsborough area there has never been any statue and all the memorial plaques were, until recently, mainly the work of American Congregationalists. On the coast, 45 miles away, are two memorials also funded by Congregationalists and neither in the correct place. ‘Locals’ seem to have seen it as a story about someone else.

With Mayflower 400, there was some growing local interest – partly because many of us have been active in re-shaping the story so that it has clear local relevance. The focus on William Brewster and William Bradford, people who were not that important while they were here, has been at the expense of understanding local context; nor has there been much awareness of what happened here after ‘they’ left.

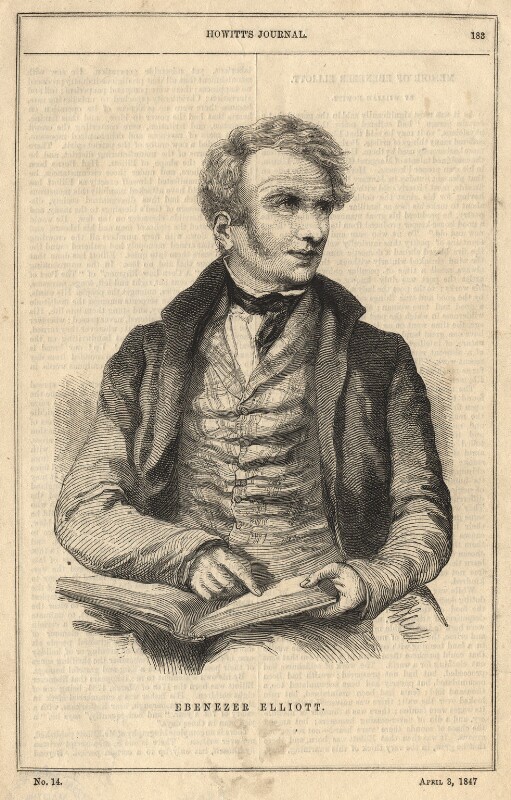

Radicalism, the Pilgrim Fathers and Ebenezer Elliott: The ‘Corn Law Rhymer’

Southampton’s Pilgrim Father’s Memorial (1913)

Memories of the Mayflower in Britain have taken many forms – from paintings and novels to poems and plays. One of the rarer but more long-lasting methods of commemoration are statues and monuments. Dotted around the urban landscape, these structures reflect a lot about what British society – both local and national – thought, at a certain time, was important about the past. Today, these can seem like simple curated objects: through their symbolism and accompanying plaques they tell the story of their makers. But, if we dig down a bit deeper into the documents and local press of the period, we can often find a different angle – and, in this case, one that suggests the Pilgrim Fathers could have both positive and negative meanings to local people.

The most impressive of all the Mayflower monuments (pictured below) was put up in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1889. Formerly known as the Pilgrim Monument but today the National Monument to the Forefathers, it was fashioned from solid granite and is a massive 25 metres tall. ‘Faith’ stands in the middle, clutching a bible and pointing to the heavens, surrounded by figures representing Morality, Law, Liberty and Education. This built evocation of Mayflower mania, coming at a time when interest in the Pilgrim Fathers was growing on both sides of the Atlantic, seems to have started the trend for monuments. Plymouth had the first in Britain: a simple granite block carved ‘Mayflower 1620’ and set into the ground near the supposed ‘Mayflower Steps’ once trod by the Pilgrims. Continue reading

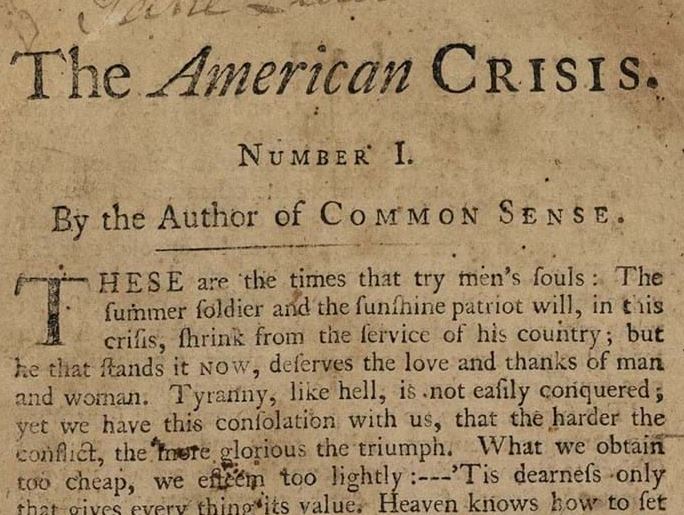

The American Crisis and Radical Pilgrims

H.T. Dickinson comments that ‘The American Revolution was the first great modern revolution and it has arguably been the most permanent, successful and widely admired’.[1] The results of this major event led to ‘the oldest surviving written constitution in the world’, and ‘a remarkably successful liberal regime’ that contrasted with the established political systems of eighteenth-century Europe.[2] Unsurprisingly such an influential event has received attention from generations of American scholars and historians. However, not as many historians have explored the British perspective on what was memorably termed by Thomas Paine ‘The American Crisis’. Britain was far from united in supporting the war with the American colonies – and indeed, for some political commentators, the story of the Mayflower provided a historical justification for American secession.

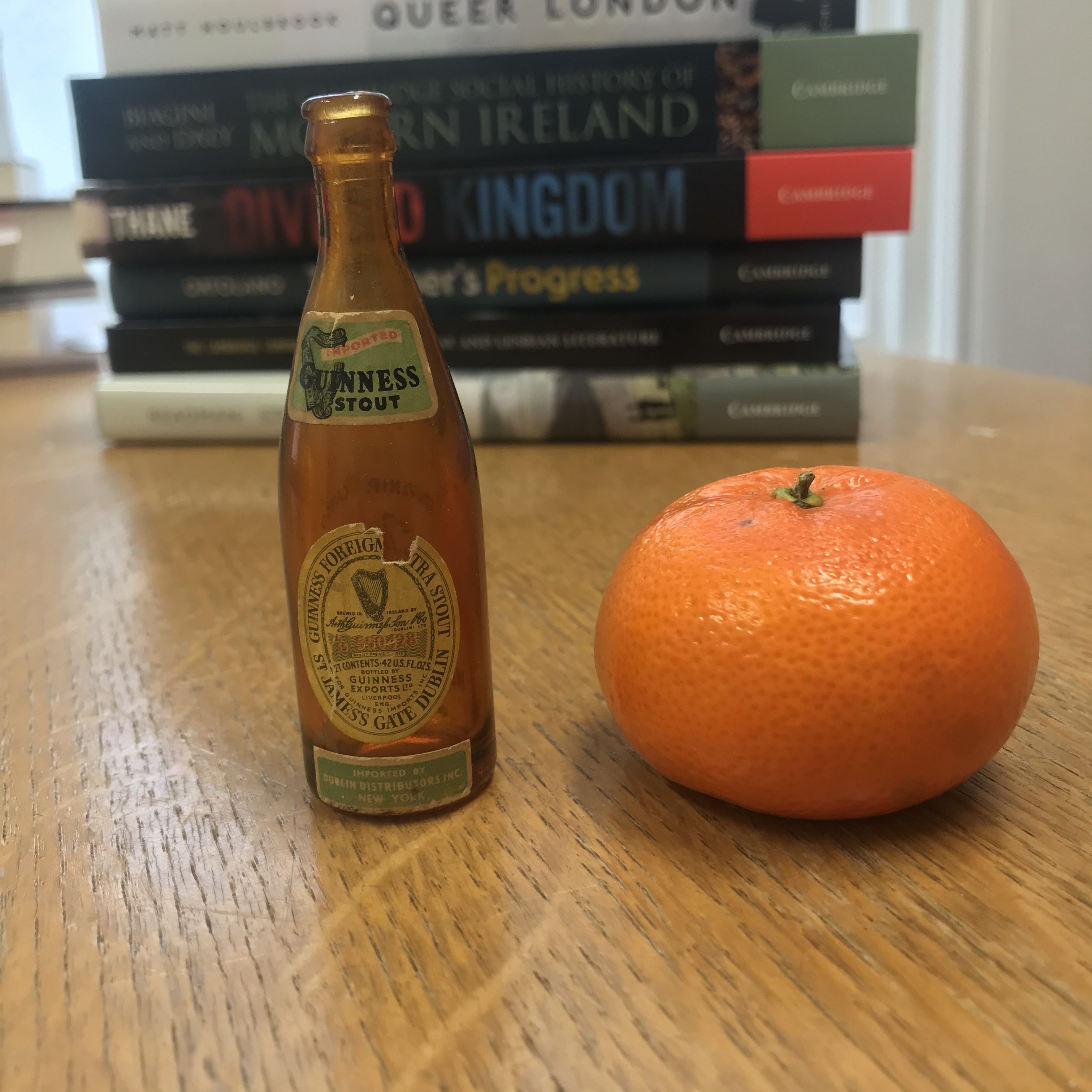

Getting tipsy on the Mayflower II

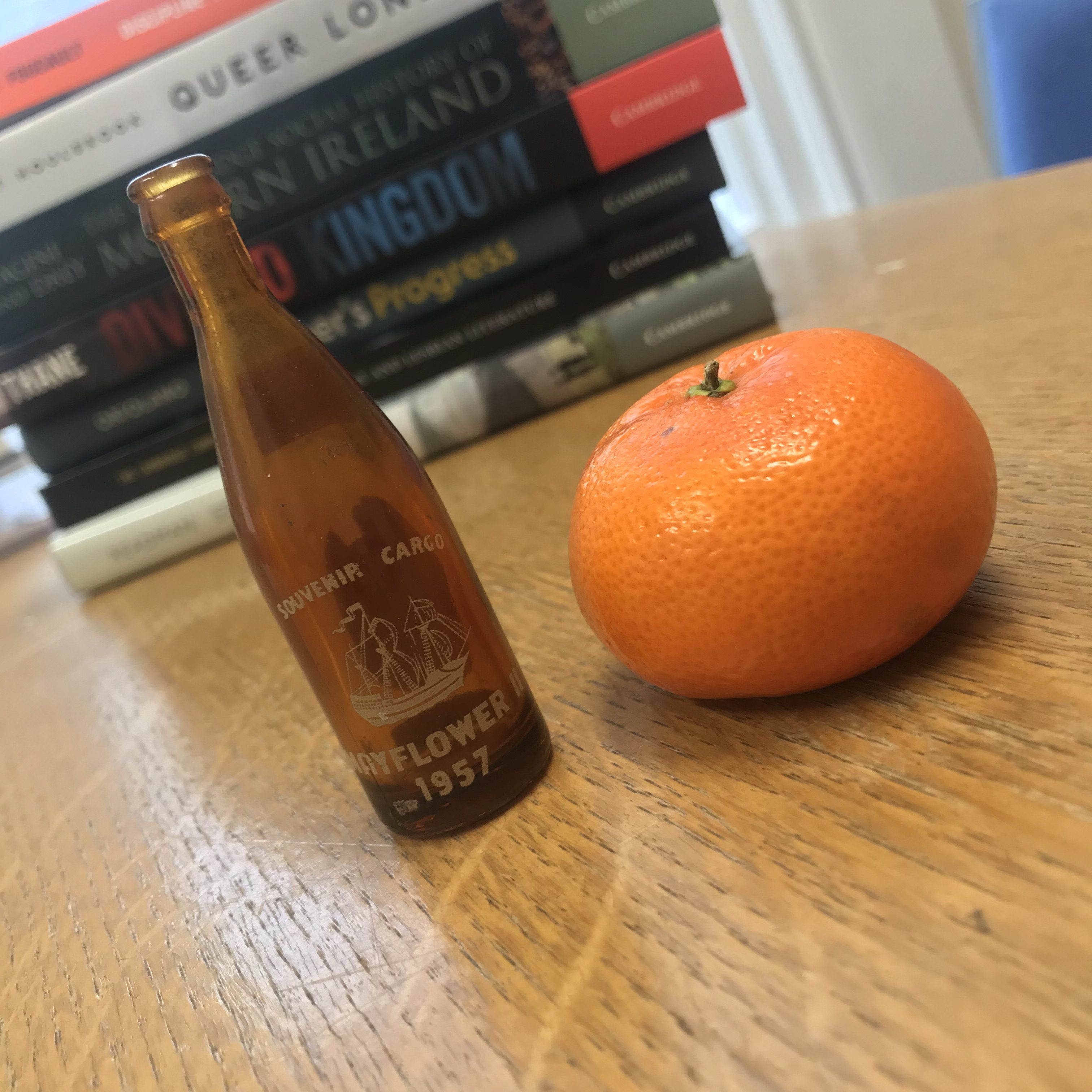

One of the most fascinating and relatively recent expressions of Mayflower-mania came with the building and sailing of a ‘replica’ of the ship in 1957. Dubbed the ‘Mayflower II’, the idea for the project came from Warwick Charlton, a then London-based public relations expert who had fond memories of serving alongside Americans in the Second World War. Like the 1917 commemorative postcard we recently featured, the Mayflower II was a project conceived primarily to support Anglo-American relations – this time, in the guise of ensuring ‘the free world’ against the backdrop of the Cold War. We are currently researching the Mayflower II – from the idea to afterlife – and will be sharing a much longer piece soon. In the meantime, to ‘whet your appetite’, the below is a miniature souvenir Guinness bottle – next to a tangerine for scale – that was taken on board the ship (along with many other examples of industry, manufacture and commerce from the ‘British Isles’). When I bought this bottle on eBay, for a price I’m not willing to admit(!), I thought it was full-size… a cautionary tale that sometimes things are not always what they seem – much like the cultural afterlife of the Mayflower!

Randal Charlton, son of Warwick, has recently written a book about his father: The Wicked Pilgrim. You can pick up a copy here

1917 Silk Postcard

This embroidered silk postcard commemorated the official entry of the USA into the First World War. It was made in England by Birn Brothers, Ltd – a large printing house that manufactured both cheap pictorial books and postcards.[1] On the front of the postcard, the Stars and Stripes and the Union Jack hang out from behind a laurel wreath and an anchor: symbols of nationhood, victory and naval power intertwined. Joining the composition together are two pennants adorned with ‘Mayflower 1620’ and ‘Allied April 1917’. Mayflower-mania had been reaching fever pitch on both sides of the Atlantic in the final years of the 19th century and especially in the lead-up to the First World War. New editions of important fiction and non-fiction works about the Pilgrim Fathers were published, monuments erected in towns and cities that linked themselves to the story, and committees formed to plan largescale celebrations for the 300th anniversary in 1920. Around the same time, a rapprochement between Britain and the USA was taking place after a long period of animosity following the American Revolution. To achieve the sense of a new alliance, diplomats – from the highest echelons of government to the everyday Anglo-American enthusiast – actually looked back to history. The tale of the Pilgrim Fathers was ripe for using as a tool to create a shared identity. ‘The return of the Mayflower’ had already become a familiar expression in previous decades, referring to the 1621 return voyage on which no Pilgrims had chosen to journey. But during the War the phrase took on a new meaning: the return in the present of now-American Pilgrims to save their mother country. Rudyard Kipling popularised this idea in 1917 when he described how the world had seen ‘The second sailing of the Mayflower’ and tentatively asked ‘What shall grow out of her return voyage our grandchildren may, perhaps, comprehend.’[2] In a bright and colourful way, this postcard captured that spirit.

[1] Metro Postcard – http://www.metropostcard.com/publishersb1.html

[2] Rudyard Kipling, ‘The second sailing of the “Mayflower”’, Daily Telegraph (August 17th 1918).

The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point

Many depictions of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ in nineteenth-century British literature offer a positive, idealised, even elegiac portrayal of the settlement of New Plymouth. After all, according to the myth popularised by Felicia Hemans, these were the brave men and women who laid the foundation of a great nation. However, the mythology of the Mayflower was also put to less celebratory uses. Perhaps the most well-known example is Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ (1848); a controversial mid-century poem that grapples with issues of race, slavery, and injustice from an explicitly abolitionist perspective. Originally intended for publication in the 1848 edition of The Liberty Bell, an antislavery annual based in Boston, Browning – born in County Durham – feared the work was ‘too ferocious, perhaps, for the Americans to publish’. [1]

John Boyle O’Reilly: Rebel, Revolutionary, and Mayflower Poet

They could not live by king-made codes and creeds;

They chose the path where every footstep bleeds.

Protesting, not rebelling; scorned and banned;

Through pains and prisons harried from the land

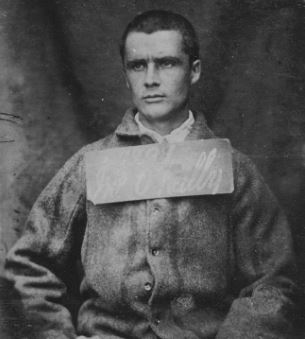

– John Boyle O’Reilly: Poem read at the Dedication of the Monument to the Pilgrim Fathers at Plymouth, Mass., 1 August, 1889.

John Boyle O’Reilly as a prisoner in 1866. Public Domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Boyle_O%27Reilly.jpg

On October 12, 1867, the convict ship Hougoumont left Portsmouth, England, bound for the Penal Colony of Western Australia. The last convict ship to ever leave Britain, the Hougoumont arrived laden with 279 prisoners sentenced to transportation. One of those men was John Boyle O’Reilly (1844-1890), part of a group of Irish prisoners who were members of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, also known as the IRB or Fenian Brotherhood. Fearful of another Irish uprising, the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood was persecuted by the British government who saw the movement as an intrinsic threat to their interests in Ireland. As T. W. Moody comments, the Fenians had revolutionary politics at their core: the brotherhood was ‘essentially a physical-force movement which absolutely and from the beginning, repudiated constitutional action […] [m]ore than any other school of nationalism the Fenian movement concentrated on a single aim, independence, and insisted that all other aims were beside the point’.[1]

The Mayflower Barn: Mystery and History in Buckinghamshire

Deep in the countryside of Buckinghamshire, in the small Quaker village of Jordans, lies an old wooden barn. Quaint, if unremarkable, it probably dates to the early part of the seventeenth century. Today, it is part of a private multi-million pound estate – still visible from the road, but shut off from the public. Rewind a hundred years, and scores of people came flocking from around the country (and even the United States) to catch a glimpse of the interior. Articles about the barn were featured in local newspapers and many of the nationals too. Amazed or dubious, journalists reported the most incredible of happenings: an Englishman, James Rendel Harris, had found the last resting place of the Mayflower.

“The breaking waves dashed high”: The life and afterlife of Felicia Hemans’ ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ (1825)

Felicia Hemans was an English poet and literary celebrity whose immense popularity rivalled any writer of the early nineteenth-century, even Lord Byron. Born in Liverpool, her family life was disrupted by the Napoleonic Wars, but her father’s wealth as a wine merchant provided Hemans with a good education at home. Her exceptional talent was noted by a tutor who lamented her gender meant she could not be ‘borne away to the highest honours at college!’.[1] Her first volume of verse Poems (1808), published when Hemans was just 15 from poetry written during her childhood, gained her early notoriety and was to be the first of 24 volumes she would publish in her lifetime. Later, she would find lasting fame on both sides of the Atlantic for her poem ‘The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England’ (1825).